|

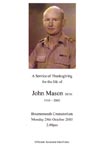

It was with a great sense of

loss that I heard that John(Mucky) Mason had died on Saturday the 8th

of October 2005.

I never met him,but he was

one of those soldiers whose name and exploits live on long after they

leave regular service,and indeed live on long after their time on this

earth.

As a young Fusilier,I had heard

tales of “The Ghost Gunner of Monte Cassino” and later made

it my business to find out more about it.

The following is just a short story(there are many) illuminating some

of the character of this highly admirable man

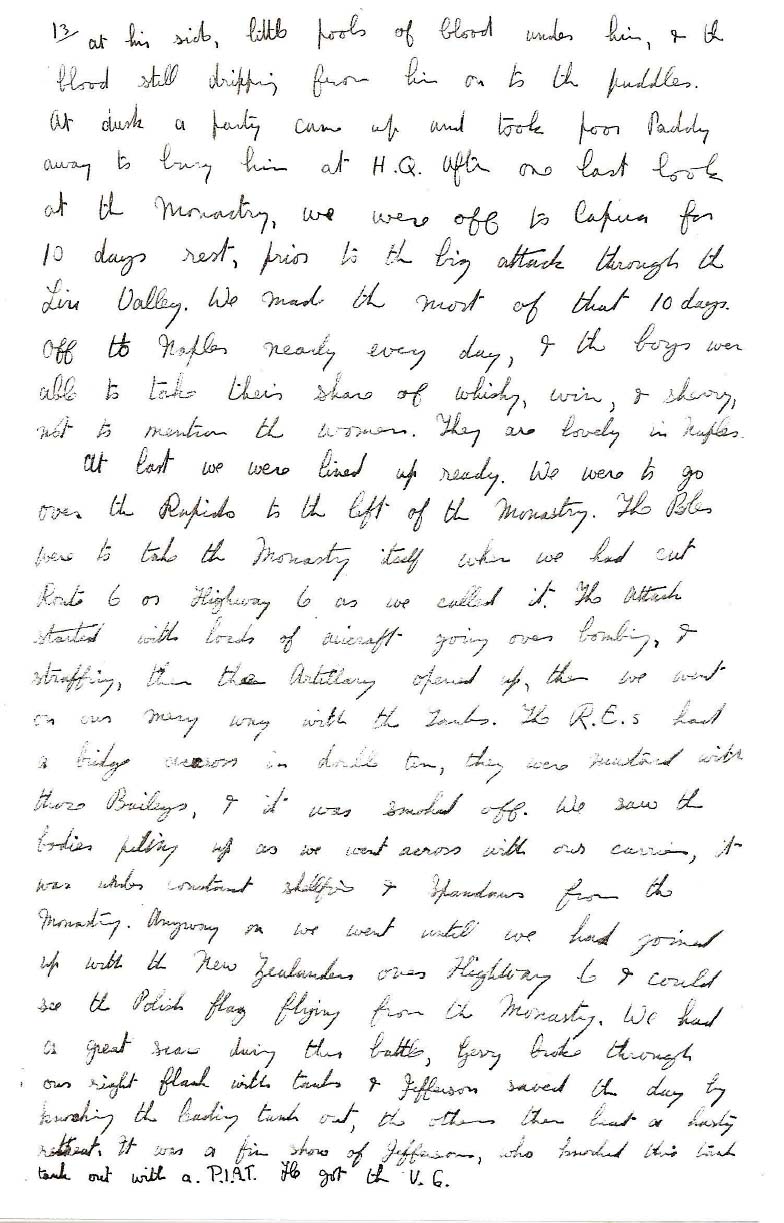

The place was Monte Cassino

Italy,and the date was 1944.

John Mason was the Pl Sergeant of the Vickers Machine Gun Platoon,of

the 2nd Bn The XXth The Lancashire Fusiliers.

The Platoon was dug into a ridge almost within grenade range of the

German positions in the Monastery,which had already repulsed attack

after attack.

The 2nd Bns positions were

so exposed that there could be no movement during daylight,and things

were at something of a stalemate.

When in close contact with the enemy and in effect pinned down,it is

important that the some kind of offensive work be done,if morale is

not to suffer.

The idea was formulated which

came to be known as the “Ghost Gun of Cassino”:-

The following is an extract(abridged) from “The Monastery”

by Major F Majdelany MC:

There were other things about Sergeant Mucky. Those who had shared slit-trenches

and dug-outs with him through three campaigns would tell you that not

a single day had ever gone by without Sergeant Mucky writing a letter

to Mrs. Sergeant Mucky. If as often happens during operations-two or

three days passed without it being possible to get mail back for dispatch,

that made no difference. The letter was written every day just the same.

Sometimes as many as six piled up before the opportunity occurred to

get them censored and sent back.

After his wife and his baby girl, Sergeant Mucky had one other love-the

Vickers machine-gun. He devoutly believed that it was the most beautiful

and splendid thing that man had ever created. To clean it and care for

it was an honour: to fire it at Germans was the highest of all pleasures:

to teach and initiate other men into its uses was an apostolic mission.

At the present time he was in charge of the platoon up on Machine-gun

Ridge. I 'phoned him and told him that the C.O.. and I would be visiting

him around seven that night, so that he could warn his sentries.

. A hoarse Lancastrian voice challenged us. The figure of Sergeant Mucky

stepped from behind a large boulder. He carried a tommy-gun and appeared

to be wearing a tea-cosy of huge dimensions. As we finished the climb,

I remarked that his headdress appeared to have surpassed itself, even

for him. He told me it was an ordinary sandbag, with the opening rolled

down into a thick lyre. It fitted neatly over the usual woolly cap,

he said, and it was very warm.

I told him about the Ghost Gun. He thought it over for a long time.

Then he smiled very broadly and said: 'It's a good idea.' We were enormously

relieved that he approved. A Lancashire soldier's approbation is not

easily won.

We had arranged for one of the reserve guns to be brought up for the

experiment. As soon as it arrived we set off into No-Man's-Land, with

the gun and a large amount of cable. The three of us picked our way

forward, John, Sergeant Mucky and myself, and after we had gone about

three hundred yards we found a spot that seemed to meet our require¬ments.

Two rocks between which the gun could be wedged and a number of small

bushes that could be used for camouflage.

Bathed in moonlight, the Monastery looked incredibly beautiful. And

horribly near.

It was a strange sensation being there with just two others in that

lonely expanse of stillness. The sudden hysterical screech of a Schmeisser.

The steady chug-chug of a distant-answering Bren. Then utter silence.

Then the low chilling burr of the M.G. 42, which is Germany's best machine-gun,

and sounds like a distant motor-cycle moving at a hundred miles an hour.

And behind us, regular as a bus service, the noise of tearing silk as

giant shells from the heavy batteries at Piedmont sped swiftly over.

Then a green light soared up near Cassino Castle. It hovered for an

instant desperately-then flopped down like a dying bird. The usual tense

reaction. Ours or theirs? A signal? For what? We waited for the outburst

of artillery and mortar fire. There was none. There was nothing but

silence. It must have been a windy sentry. Tearing silk again. Screeching

Schmeisser again. Three screeches-long screeches. Then silence.

One was conscious of being very near to danger without being afraid

in the way one is afraid while being shot at. The danger was impersonal.

In a way it was exhilarating. A sort of emotional astringent. I imagine

it was something like the feeling mountaineers have during a difficult

climb.

The bright moonlight added to the general eerieness. You could see the

Monastery so clearly you felt it must be bound to see you-though you

knew that was impossible.

We had a lot of trouble fixing the two-hundred-and-fifty¬round belt

so that it would feed the gun automatically, in the absence of a man

to hold it, but the job was eventually done. The gun and the ammunition

were immovably wedged in position. The muzzle was pointing towards the

windows at the right or northern end of the Monastery¬the end the

shells could not easily reach, and therefore the best preserved part

of the building.

Well pleased with ourselves, like schoolboys who have at last managed

to put together a complicated new toy, we turned our back on the screech

of the Schmeissers, and crept slowly back towards the ridge and the

noise of tearing silk. As we went along we set the cable, which we'd

attached to the trigger mechanism of the gun, against smooth rocks which

would act as pulleys.

Back in the little cave, which was Sergeant Mucky's headquarters, we

held our breath as the great moment arrived for the first pull. John

solemnly grasped the cable and tugged. Nothing happened. We each had

a pull in turn. Nothing happened. There seemed to be a lot of play in

the cable, and it was like pulling elastic. We had a final despairing

tug together. But the gun wouldn't play. With one voice we swore. Then

we wearily made our way back to the gun. Nothing had moved. The connections

were still secure. It must be the cable. So on the way back this time

we selected the route for the cable more carefully and succeeded in

eliminating several corners.

Once more we pulled. This time, to our unspeakable joy, there was a

triumphant rattle in front, and half a dozen rounds zipped away towards

the Monastery windows. We were so delighted with our success that we

couldn't leave the toy alone. We went on having pulls to see who could

get the longest burst away, until the gun jammed. Then we made the journey

out into No-Man's-Land for the third time to load the gun with a new

belt. Back in the cave, we just had one more short, sharp pull to make

sure the thing still worked. Then the temptation to go on playing was

sternly resisted.

The Ghost Gun plan was explained in detail to Sergeant Mucky. Each morning,

shortly after first light, he was to take a new belt out, and aim the

gun carefully at one of the Monastery windows-a different window each

day. Then at intervals throughout the day he was to pull the cable and

loose off a provocative burst. When the answer¬ing machine-gun and

mortar fire came back-as it cer¬tainly would-he was to let it have

its say. Then after allowing the Boche time to pat themselves on the

back for silencing our gun, he was to fire another burst, which would

serve as a sort of rude gesture. This was calculated to enrage the Herrenvolk

and tease them into wasting a lot of ammunition on an unoccupied area;

to act as a general

The Ghost Gun was a great success. It gave the machine ¬gunners

a new interest in life. Every day it fired its teasing little bursts

at the Monastery windows. And the rising tide of the Herrenvolk's irritation

was clearly revealed by the increasing weight of stuff they were throwing

back at it whenever it fired. The first day they didn't bother very

much. They replied, but only to the extent of a burst or two from one

of their own machine-guns. By the fourth day they were beginning to

look for it in earnest. Every time it fired they searched the ground

very thoroughly with anything up to six guns. Finally, they honoured

it with a royal flush from two of their mortar batteries.

Sergeant Mucky kept a careful log of the number of rounds they wasted

on it. The figures were quite impres¬sive, and very gratifying,

as the Boche, like ourselves, also had to carry all their supplies up

a tortuous mountain track to the Monastery, and' as with us, men bad

to carry it from there to their forward positions.

It became very famous, our Ghost Gun. Mainly be¬cause there was

little else in the daily dreariness on which the atrophying mind could

fasten. It assumed a gigantic importance. Everybody got to hear about

it. The whole battalion followed its adventures with breathless interest.

Its fame spread beyond the unit. People rang up from other units and

said: `Tell us about the Ghost Gun. We want to have one, too.' Visiting

generals would say: `How's the Ghost Gun? Jolly good idea!' Then they'd

roar with laughter.

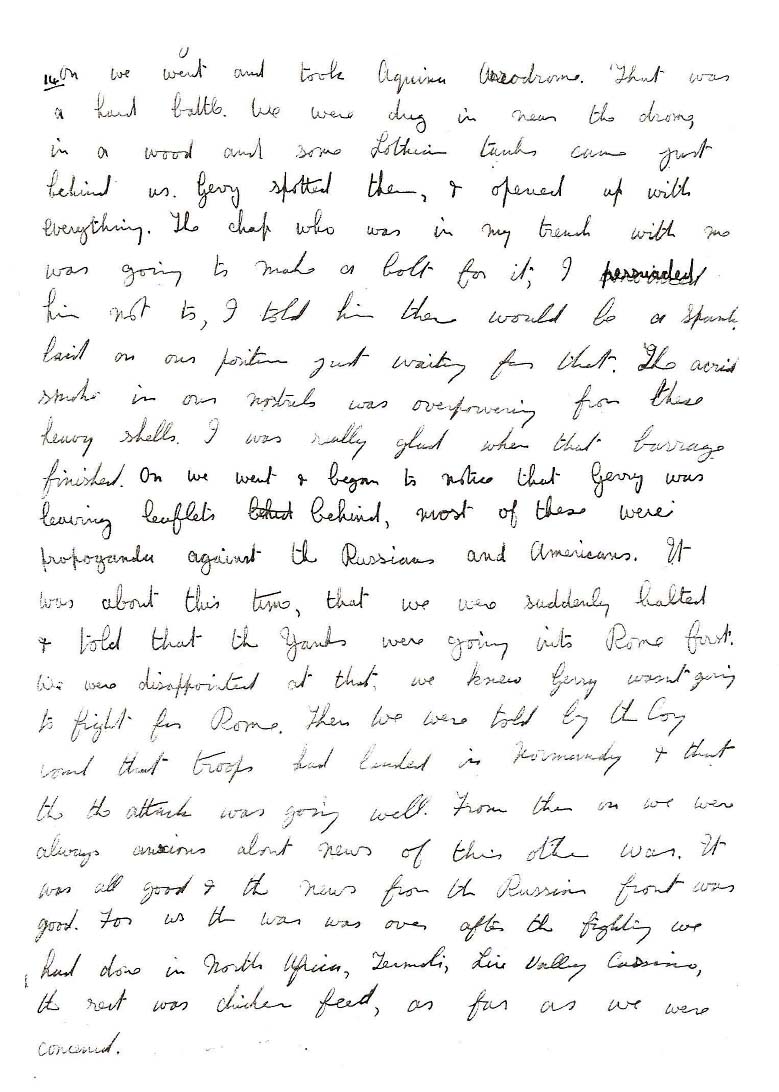

Just one period in the service

life of this fine soldier.

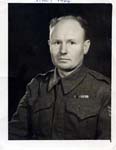

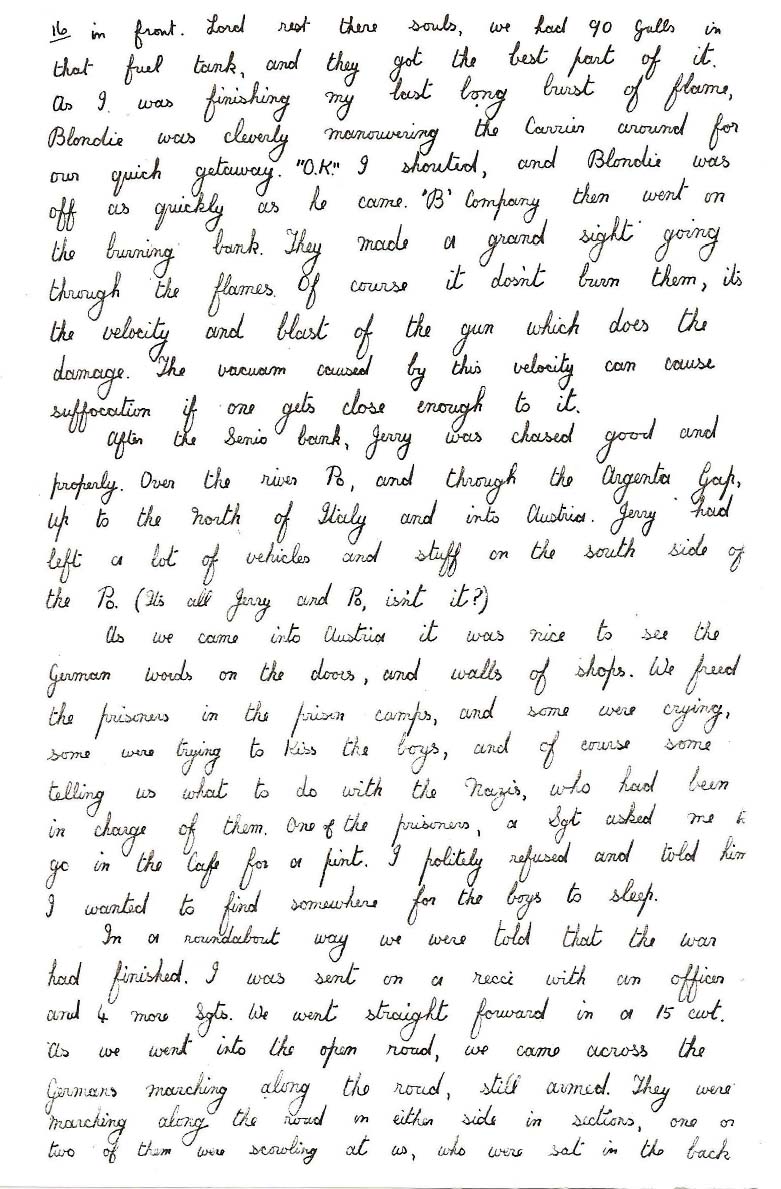

This photograph dates from June 1948

- just four years after the Battle of Monte Cassino – and

shows the original crosses that were placed in the cemetery following

the campaign.

This photograph dates from June 1948

- just four years after the Battle of Monte Cassino – and

shows the original crosses that were placed in the cemetery following

the campaign.

In the background Monte Cassino,

which was bitterly fought over, looms large over the cemetery.

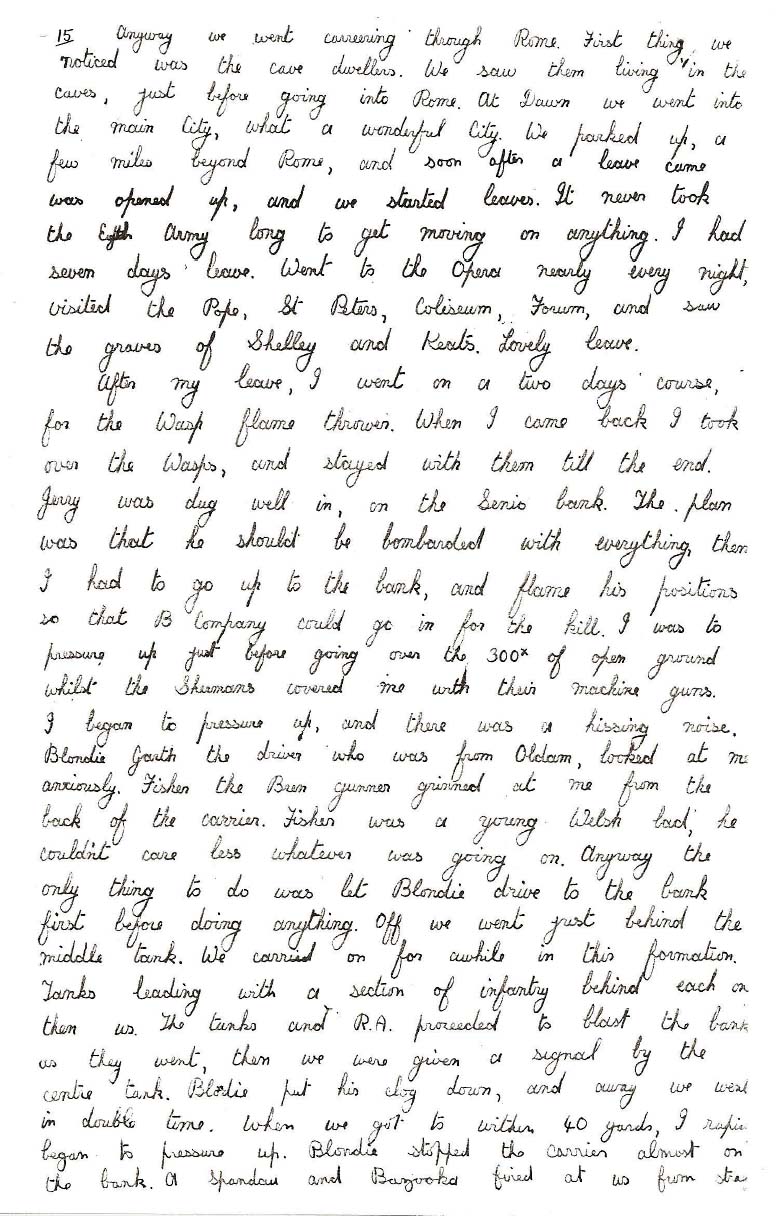

|

|

|

A

|

B

|

C

|

D

|

|

1

|

|

|

|

|

|

2

|

|

|

|

|

|

3

|

|

Tommy was obviously a mate of

John's

|

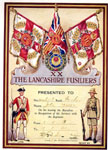

John's leaving Certificate from

1st Bn at the end of 1939 to go to the 2nd Bn |

|

|

4

|

|

|

|

|

You will see that throughout

his service with the Lancashire Fusiliers he remained a shining example

to all around him.

We extend to his family our

deepest condolences and respect.

Stand Easy Sergeant .

Captain (retd) J Eastwood BEM

CQSW.

The Tooth

Brush story or how John meet his wife

John went to a dance in Bournemouth

with another Lancashire Fusilier, Buddy Rogers, in 1941 before going

overseas for the war. He saw my mother and thought she looked lovely

but was afraid to ask her to dance as she was 'too good for him'. An

excuse me dance came on and his mate said 'come on Onmia Audax!' After

the dance was over he asked to walk her home but she told him she didn't

walk home with soldiers. During the evening, he had got the information

out of her that she worked in a chemist shop so the next day that he

had off he took a circular route of about five miles visiting every

chemist shop. He had just about given up when he found her in one of

the last shops. He then turned out his pockets to show her he had bought

a toothbrush in every shop he had visited!

|