First Person is your column, in your own words. There

we no restrictions on topics, but preference will be given to articles

which are bright, concise, of general interest and not more than 650

words. Send your article to First Person, The Courier-Mail. GPO Box

130, Brisbane, Qld, 4001.

First Person

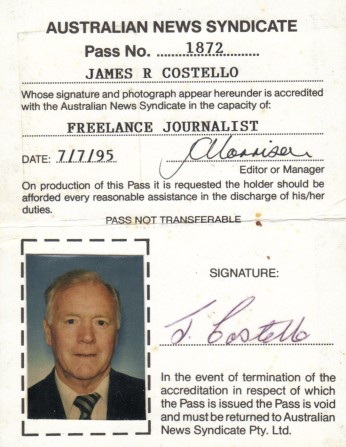

By James Costello

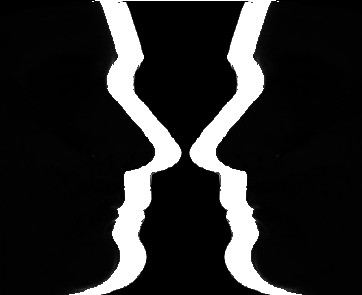

Face to face, two metres apart; one of us was going to die. His eyes

were full of hate, but I could smell his fear, or was it mine? I had no

more rounds in my rifle, just a bayonet on the end. He, the same.

I lunged at him, he jumped back. He lunged at me, I jumped back. Then

we stood as two breathing statues, each waiting for the other to make

the next move.

The noise of the battle around us seemed to subside. Explosions, machine-gun

fire, the screams of the dying. All faded away as though in another world.

Only he and I were in this world, and one of us was going to die.

He came at me again. I parried, knocking his rifle down only to feel a

scalding-hot, stabbing pain in my right thigh. For a brief moment our

bodies touched as we continued our dance of death.

I brought the butt end of my rifle up and smashed it into his face. His

blood splashed into my open mouth. It didn't taste salty, the way people

say it does.

Mother of God, why in hell's name did I join up?

Mother, where are you now when I need you most? You always said that you

were proud of me the way I could look after myself. But, if I'm going

to survive, I need you now.

He Jumped back again and brought his rifle up to the on-guard position.

Once again, we stood facing each other, his blood

in my mouth, my blood on his bayonet.

My right leg gave way slightly, but I quickly stiffened it up. Mustn't

let him see me weaken. Then his eyes spoke to me. I've got you, I've got

you now. His confidence, my fear; not much of a match really.

Where are my bloody mates? Some of them should have been behind me when

I jumped into this trench.

I remained frozen in the Turkish heat as he made his next move. His bayonet

slid into my stomach.

Mother, how did you manage to bring us five kids up during the depression?

With Dad dead and us always short on food and clothing. It must have been

a struggle for you. Yet, you were always there to wipe away our tears

and fears.

Mother of God, where are you now?

With his bayonet in my belly, he was very close to me. So I pushed my

rifle upwards and watched my bayonet slice into his throat. I'll never

forget the vivid look of surprise in his eyes, .the look of a man in the

last moments of life.

He must have had a mother as well; is he thinking of her now - now that

he's dying?

He slumped to the floor, the momentum pulling his bayonet from my guts

as he fell. I wonder who he was? Still he's dead, I'm alive.

Mother, you'd be proud of me now if you were not lying in that damp, cold

cemetery. I can still look after myself.

I made my way to the end of the trench that was bathed in sunlight I must

get out of this bell. Strangely, I felt no pain as I walked; maybe I'm

not seriously hurt after all.

As I moved into the sunlight, I turned to look at him and was shocked

to see my body slumped across his.