Reflections

on The Past

It was said that during the years between

1930 and 1939, a man joined the Regular Army because he was considered

to be a complete drop-out from Society.

This is far from the truth however, because

first of all you must remember that during these years, there were no

DHSS Handouts as we know them today, and with unemployment in the order

of 30% of the working population, most of the workers were trying to

exist on some 10 shillings a week, in terms of today's value this would

be 50 pence.

You have only to look at the living conditions

being experienced by the Welsh Miners and the workers in heavy industries

of the North during these years to understand the squalid conditions

in which they were forced to live.

Indeed, these conditions motivated some thousands of these workers to

march to London as the "JARROW MARCHERS" in an attempt to

prod the government into providing employment. Needless to add, the

Government did nothing.

Hitler had the same unemployment problem when

he came to power in 1933 and promptly solved the problem by initiating

a massive Public Works Programme, and as we were to learn to our cost,

an equally massive re-armament programme.

In England we did nothing to solve the problem.

Infact, it took a declaration of war, in 1939, to solve it by simply

introducing Conscription into the Armed Forces., for all suitable men

and women and directing the rest into War Work.

During the 1930s, a boy in so called working

class was expected to leave school when he was 14 years of age, in order

to seek employment to supplement the family income.

This was bad luck for a boy with an aptitude for further education,

because; regardless of the fact that he could be awarded a Scholarship

to attend the local Grammar School, in no way could the family afford

the extra expense involved.

As far as the girls were concerned, it was

expected they would enter into "Service", which of course,

meant drudgery, in the full sense of the word. Involving the waiting

on, hand and foot, on the more fortunate "Gentry".

The alternative was to obtain employment as waitress or shop assistant.

With these facts in mind, jobs for boys such as errand boys and other

similar dead end jobs were reasonably available, but at the age of 18

years, when he might reasonably expect an increase in his wage packet,

he in turn, was thrown out of work and into the dole queue.

It was only natural, therefore, that young

men looked to the Regular Army as a means to provide three square meals

a day. A spending allowance of some 10 shillings a week, with clothing

and accommodation thrown in for luck. Also the means to provide the

opportunity to visit all parts of the world. Such travel would normally

be completely out of his reach.

Having decided that Service in the Regular

Army could provide a better and more exciting life-style compared to

what he could expect by remaining in civilian life, the next question

was how and where to enlist.

In all big towns in the UK, were Territorial

Army Drill Halls, staffed by a Regular Army Soldier, Usually a Sergeant

Serving in his local County Regiment. This soldier was not only the

custodian of all the military hardware in the Drill Hall, But combined

these duties with that of a Recruiting Sergeant. You therefore arranged

an interview with him and made known your wish to be accepted into the

Regular Army.

At this first interview, you would probably

be asked to apply for enlistment in the Brigade of Guards Regiment.

The breason for this is the fact that he would receive a higher Recruitment

Fee. If you were accepted for Service in a Guards Regiment. Unfortunately

for him, however, the majority of potential recruits could not provide

the high physical standard required by these regiments. Particularly

the height requirement.

You were therefore faced with the problem

of which Unit to apply for. Armoured, Signals Etc.There was also the

problem that you may not possess the necessary qualifications to enable

you to be accepted into a specialised Unit. As an added problem, not

all the Units would be recruiting at this particular time. This could

mean that taking all these factors into account, you could well be persuaded

to enlist in your local; county regiment, which of course would be an

Infantry Regiment.

After all this hassle, you sat back, to await

a letter from the Regimental Depot for a medical examination and future

documentation. On receipt of this letter, you would prepare yourself

for your first experience in the Regular Army.

In the case of a boy, being 14 years of age, and wishing to enlist as

a boy musician, the case was slightly different in that he would first

require his parent's permission to enlist.

He would also have to satisfy the Bandmaster

of his selected Regiment, that he was sufficiently educated to enable

him to become a skilled musician. Care would also be exercised in selecting

such boys for enlistment, in that he would require uniforms to be made

for his particular size and special facilities would have to be made

available for his welfare.

On arrival at the entrance to the Regimental

Depot, you marched down the driveway in what you considered to be a

most soldier like attitude, to be confronted by an immaculately dressed

soldier.

From his Cap Badge to his Boots, everything

was polished and gleaming. Needless to add, he took not the slightest

notice in my arrival.

At this stage, I was yet to learn that a soldier on sentry duty was

only interested in anything that looked to be Officer Material crossing

his path, in which case, he would be galvanised into action and slap

his rifle with consummate ease, to perform the appropriate salute. The

Officer would then return the salute with a flip of his cane to his

cap. Such is the way of Officer Material when dealing with other ranks.

The soldier was not going to afford me such respect, however, and would

certainly not invite the wrath of the Regimental Sergeant Major by talking.

You therefore entered the Orderly Room, which was staffed by equally

smart soldiers; all dressed in their best uniforms, and made known the

fact that in accordance with instructions, you had arrived to form part

of their illustrious regiment.

After looking at you as if you were something

the cat had brought in, regardless of the fact that you were wearing

your best 50/- shilling Taylor's blue suit, complete with turnips. The

Orderly Room Sergeant would detail a soldier to escort you to a barrack

room containing some twentfour iron framed beds. On each bed would be

stacked three Biscuits (Not the edible type) but Hessian filled squares

which served as a mattress, three blankets and two sheets, uttering

the ominous words, "sooner you than me mate". The soldier

would then tell you to stand by for future orders.

During the next few hours, there would be further recruits arriving

at the Depot until there were some twenty-four, nervous potential soldiers

assembled in the barra ck room, all of whom had received the same reception

as you.

In retrospect, I was to learn that this number

of recruits would form a training squad and each squad would be named

after a particular Battle Honour awarded to the regiment. It is also

true to say, that each squad of potential soldiers, would represent

all walks of life. Be it tinker, tailor soldier, sailor, rich man, beggar

man and thief…

All these recruits would be wandering around the barrack room, asking

questions of each other and wondering if they had done the right thing

in joining the army.

The next phase would be for all twenty-four

recruits to be directed to the medical Officer for a medical and dental

examination. This examination would be fairly stringent, and particular

regard would be given to eyesight and feet, which were possibly the

most important medical requirement for a soldier serving in an Infantry

Regiment. A recruit who required glasses to read, or suffered from flat

feet, would not be accepted for the Service.

After this medical and dental examination

you would report back to the Orderly Room to accept what was known as

the "King's Shilling", which committed you, body and soul,

for seven years with the Colours and five years Service with the Reserves.

So came the saying, which all soldiers had said at sometime in their

Service, "Roll on My Seven".

All recruits would now report to the barrack

room to find that in their absence, they had been allocated, A Full

Sergeant, A Lance Sergeant and a Lance Corporal, all of whom had been

detailed to act as their instructors for the next six months until they

had completed their basic training at the Depot.

As soon as you had been introduced to the

Sergeant, the introduction took the form of a bellow to "Get Fell

In". You proceeded to the hairdresser for your first experience

of an Army Haircut. This was a very simple matter of running the clippers

up and over the crown of your head, after which, with any luck, you

might be left with a slight bristle on top. It is true to say that many

a recruits' vanity was left on the floor of the hairdressing saloon.

After this experience, you proceeded to the Quartermaster's Stores,

to be issued with your webbing equipment and clothing, together with

all the accoutrements which made up your army gear,

This session was an example of efficiency, never seen before, or since.

You would be issued with a kit-bag and with a stentorian voice; the

quartermaster would call out each item as it was issued. Eg.Kit-bag,

soldiers for the use of, "One". As you shambled along the

counter, stuffing clothes into your kit-bag as it was issued…

Eventually you came to the end of the counter, and then, to add insult

to injury, you were expected to sign for this lot, regardless of the

fact that you did not know precisely what you were signing for. The

only pause in this programme would be to inquire the size of your head,

and on reply, an S.D. Cap, jammed on it. (With of course), Soldiers

for the Use Of, ONE. If the size was wrong and it came over your ears,

the whole conveyor system would slide to a halt, much to the disgust

of the quartermaster.

After all this drama you would creep back

to the barrack room in order to unload all this military hardware and

clothing onto your bed, and to wonder where it all fitted and where

it went. This pause was not to last however, because you now had to

assemble all your equipment and learn how to fold all your clothing

and bedding in preparation for the morning inspection by The Orderly

Officer.

With this in mind, the L/Corporal Instructor

would come into his own and detail all recruits to look at all his equipment

clothing and bedding which had been assembled as a demonstration module

and to inform all their kits would be equally immaculate for the morning

inspection, or else.The inspection by Orderly Officer the following

morning would be the first chance to sort out the wheat from the chaff,

because however hard they tried, some recruits just could not master

the art of general cleanliness and to maintain their belongings in the

manner expected by the army.

This is when army discipline would first begin

to be applied, because no excuse would be tolerated for what, in the

Army "Jargon", would be called, "slovenly behaviour".

In fact, the army had a name for just about everything you could commit.

When all else failed, you could be charged with "Dumb Insolence".

You just could not win. The simple answer was of course, to keep out

of trouble as much as you possibly could.

To arrange your belongings for the morning

inspection, you would first of all, telescope the two parts of your

metal bed into one. Then place your three biscuits on top of each other

and stack them at the rear of the bed. You then would then fold two

of your blankets and fold two folded sheets between the blankets, and

finally encircle them with the third blanket. The resulting package

would look very much like a Liquorice Allsorts. This would then be placed

on top of the stacked biscuits.

Your webbing equipment would be completely

assembled and suspended by the shoulder straps, hung on the two protruding

pegs fitted to the wall behind the bed. The equipment would then be

opened up flat against the wall by means of a length of wood behind

the webbing belt.

Your walking out cane would be inserted through the bayonet frog and

placed over the two pegs, enabling your bayonet to be suspended in the

centre of your equipment.

Bolted to the wall behind the bed would be

a cupboard containing your belongings and on top of this cupboard would

be your mess tin, encircled by your white belt… Suspended on a

coat hanger on the side of the cupboard would be your spare tunic and

greatcoat.

Standing in a wooden shoe next to your bed would be a br4ass plate,

proclaiming to all and sundry, your name and army number.

All equipment, brasses and buttons would need

to be polished every morning in order to pass the scrutiny of the Orderly

Officer at the morning inspection. As far as cleanliness of the barrack

room was concerned, each recruit would be responsible for the immediate

area around his bed and a Roster would be maintained, appointing each

recruit a specific task is it cleaning Ablutions, Fireplace, Windows

or centre part of the barrack room floor. The floor would be highly

polished by means of a hefty piece of iron work with bristles, called

a "Bumper". This was a lethal piece of ironwork because it

was not unknown, when swinging it in a rhythmic manner across the barrack

room floor, for the operator to lose control with disastrous results

for anyone in its path.

By the end of your first day's training, you

would have learned that recruits joining the regular army would have

originated from all walks of life and from all parts of the United Kingdom.

In any particular squad under going training you would hear accents

from the Highlands of Scotland. The Geordie accents of the north, to

the cockney mimicry of London and the lilting accents of the Welsh valleys.

You would also have learned that the army

had a fascinating habit of referring to a soldier by a nickname as distinct

from his proper name, for example. A Smith would become known as Smudger.

A soldier named White would become Chalky. Equally, a Bell would become

Dinger. A tall soldier, Lofty and a short soldier, Shorty. Needless

to add that a soldier from Ireland would be Paddy. If a soldier did

not have a name that readily lent itself to a nickname, but was a bit

ungainly, he would become known as Hoppy. In the case of recruits serving

for, example in a Welsh Regiment, there might be several of them answering

to the name of Jones. In such a case it was practice to identify each

particular soldier by the last two numerals of his Regimental Number,

E. G. Jones 60. It would follow his nickname would become 60.

.

The terminology of a recruit would now begin to include foreign sayings

and words, which had been picked up by years of Service by the British

Army in all parts of the Empire. His "Bond hook" would mean

his rifle. "Possee" would mean, jam. "Panni", water.

"Chai", Tea. "Dhobi", would mean his washing and

so on. It was in fact, a language of its own.

He would be learning that Regiments would

have their own particular nickname. The 11th Hussars were the "Cherry

Pickers" because one group had been captured in an orchard during

the peninsular war. From their long Service in Ireland, the 4th Dragoons

Guards were the, "Mounted Micks" and the 9th Hussars, The

Dheli Spearmen.

Leading the Infantry of the Line came the Guards of the Grenadiers,

"The Coal Heavers". The Cold stream Guards, "The Nulli

Secundus". The Scots, "The Jocks" and The Irish, "Bobs

Own", because Lord Roberts had been their Commanding Officer

From the battle of Athera, where the Commanding Officer of The Middlesex

Regiment had exhorted his men die Hard, The Regiment became known as

"The Die Hards"The Seaforth Highlanders, from their cap badge,

were simply known as "The Kingsmen"

From their initials, The Duke of Cornwalls Light Infantry were the "Docs".

From their original number The Suffolk Regiment were known as "The

Old Dozen".

Sadly, a number of these old Regiments have now been disbanded or amalgamated

into other Units.

After your first night at the barracks, you

would be awakened at 0630 hours by the strident notes of the bugle sounding

Reveille, Indeed all your future duties and activities in the army would

first be heralded by a particular bugle call. There would be a call

for every occasion, be it getting up in the morning to lights out at

night.

Over the years, soldiers have concocted certain ribald words to suit

each particular call. Some of the more well known words would be, "Come

to the Cookhouse Door Boys, Come to the Cookhouse Door", or possibly

"Fall in A, fall in B, fall in Every Company".

One of the lesser well known calls would take the form of, "You

can be on Jankers as long as you like, so long as you answer the call".

Each bugle call would be prefixed by a particular sequence of notes,

peculiar to each Regiment.

This, no doubt, originated from the time when Regiments were billeted

close together and it was necessary to determine for which Unit the

call was intended. If there were no Regimental call, all and sundry

would be rushing to answer the call with the resultant chaos.

As soon as Reveille had sounded, the Orderly Sergeant would burst into

the barrack room, extolling all to get out of bed. One recruit would

then be detailed to proceed to the cookhouse in order to collect a pale

of tea, called, "Gunfire", which all recruits would gratefully

swallow whilst they feverishly attended to their kit in preparation

for the morning inspection. You would then line up in the ablution block

for a vacant wash bowl, in order to have a wash and shave. This could

be a particularly onerous task because no hot water would be available

for shaving and all your ablutions had to be completed in freezing cold

water.

All this preparation had to be completed by

0730 hours, because at this time you had to parade for physical training,

dressed in shorts and gym shoes.

This parade would finish at 0800 hours; you

would then have to rush back to the barrack room to change into fatigue

dress and to parade at the cookhouse for breakfast. This meal would

generally consist of porridge followed by fried egg or sausage, together

with bread and margarine, and tea.

The system of messing would be for twelve soldiers to be seated, six

a side of a long trestle type table.

The two soldiers at the end of the table would act as mess orderlies,

and would be responsible for the collection and distribution of the

meal. As an example, the orderly would collect a tray of fried eggs

and he would then divide this ration into twelve portions for distribution

to each soldier. Needless to add, that ten pairs of eyes would be watching

very carefully, .the fairness and the calculation of each portion.

At the end of the meal, the Orderly Officer, attended by the Orderly

Sergeant, would inquire at every table, if there were any complaints

relating to the cooking of the meal.

It made little difference if in fact a complaint was made because the

Orderly Officer would then daintily taste a portion of the food and

would express his delight at the quality.

When you were first issued with your clothing

and equipment, all these items would have been completely new, and as

a result, would need to be cleaned and pressed to a very high standard.

The first skill to be mastered would be that of "Blancoiing"

your equipment. This task would first of all require you to strip all

equipment of brass work, then to place the webbing straps etc, on a

flat surface. You would then use a flat brush to paint the straps etc,

with a khaki coloured paste, called "Blanco". The end product

should result in a matt khaki coloured finish to all your equipment.

The brass work would now be highly polished

and fitted to the equipment. The whole operation could well have taken

a couple of hours of dirty work. Furthermore, this operation might have

to be repeated every time your equipment was used.

The art of blancoing was a skill not always

achieved by every soldier, some of whom could never attain the even

matt finish required. In such cases, it was not unknown, for a soldier,

more skilled, to undertake this work on his behalf for a small remuneration.

Your overcoat and tunic would have been issued

with general service type buttons. These would have to be removed and

replaced by a Regimental type peculiar to each Unit. With this in mind,

every soldier would have been issued with a cloth wallet, containing

needle and cotton, referred to as a "housewife". It was quite

entertaining to watch a soldier undertaking this task, because it was

more than likely to be the first time he had ever sewn a button on in

his life.

Sometimes it was possible to obtain a set of buttons from a time expired

soldier for the princely sum of one shilling. This would save hours

of work, which would otherwise be necessary to achieve a high polish.

Your boots would be considered things of

beauty, for you could see recruits spending endless hours of toil, using

all sorts of theories such as a hot spoon to remove the pimples found

on the toecaps of his new boots. The end result would be a mirror-like

finish to his footwear. It was nothing to see a recruit fidgeting about

on a drill parade in the attempt to stop a fool scraping his toe caps

with a rifle butt.

The chin strap of your SD Cap would also require

a mirror-like finish, with of course, the brass "D" piece,

which altered the length, always being on the right.

Finally, your cap badge and collar insignia, commonly called, "Collar

Dogs" would need to be highly polished, both front and back

Your Service Dress Tunic would have to be

altered by the depot tailor to ensure a perfect fit, but the recruit

would still be required to keep the Tunic well pressed with particular

regard for a crease down the back. Intelligently called a "bum

freezer".

By this time, recruit training would have started in earnest, with a

syllabus covering, education, physical traing and map reading.

With regard to education, this aspect of training would be supervised

by a Sergeant, seconded from the Army Education Corps and the whole

subject would be divided into three examination levels. .

The primary level was called a third class

certificate. And would require a pass standard in arithmetic and Regimental

history. It is interesting to note that, a recruit would not be allowed

to graduate from the depot until this examination had been passed.

The next level was called second class certificate and would probably

be equal today's "O" level. Maths and English You would need

to pass this examination before being considered for promotion.

The final level was a first class certificate.

This examination would probably be equal to that of today's GCE "A"

level in Maths and English, but would also a proficiency in a second

language. You would be required to pass this examination before promotion

to a Warrant Officer Rank.

Physical traini8ng was under the direction of a Sergeant, Seconded from

The Army Physical Traing Corps. And would consist, in general, of normal

exercise movements.

The Army was however, very keen on promoting

Sport. In any shape or form, and considerable emphasis was placed on

this aspect of training.

If any recruit showed promise in a particular sport, he would be given

every opportunity for further training and, with this in mind, he would

also be excused all fatigues,

Considerable emphasis was placed on Foot and Rifle Drill. There were

reasons for this, because after spending months and possibly years of

training on the Square, A Soldier would obey a command instantly and

without question. This obedience would stand him in good stead in time

of war, when hesitance in obeying a command could well jeopardise the

safety of not only him but other soldiers relying on his actions.

In order to maintain some measure of unison

with each other when performing a drill movement, each recruit would

shout out the timing of the movement. With several Squads Drilling at

the same time, it could be bedlam when a recruit was learning the art

of Foot and Arms Drill; there were certain hazards to be mastered.

The first might be related to the command

, "Fix Bayonets", at which command, amongst other things,

the recruit was expected to secure his bayonet on the end of his rifle

by means of a small spring operated plunger. The snag was, however,

that you were not allowed to look downwards at the rifle to ensure that

all was well and truly secured. If this was not the case , the next

time you "Sloped Arms", the bayonet would make a beautiful

arc into the rear rank of soldiers, resulting in unprintable remarks

from the Drill Instructor.

The second hazard might also be related to

the command, "Right Form". This was a highly complicated manoeuvre

at the best of times and when being executed by inexperienced recruits,

the results could be disastrous.

This manoeuvre, the right hand man to give a ninety degree turn to his

right, take two steps forward and remain Marking Time.

The remainder of the squad would make a half right turn and pick up

the dressings on the left,

If the right hand soldier botched it up however, you would be faced

with soldiers wandering all over the Square and wondering if it was

best to go home…

Weapon training would consist mainly of achieving

a high standard of proficiency with the Lee Enfield Rifle. You would

be taught to shoot accurately by following the doctrine, "Get the

Tip of The Foresight in line and in the centre of the U of the Back

sight. Sights thus aligned Focus" the Mark. You would also be expected

to fire ten rounds in one minute, with reasonable accuracy.

The highlight of this training would be a

visit to the Rifle Range in order to calibrate the Sights of his Rifle.

The rifle itself would be clean on all occasions and would be what the

army called," Clean, Bright and Slightly Oiled".

It is true to say, that a soldier seemed to

spend all his spare time with a "Pull Through" and lashings

of material referred to as , "Four by Two"in an attempt to

keep his rifle clean at all times. To accuse a soldier of having a dirty

rifle, was a crime only slightly removed from murder.

Weapon training would also include the use

of automatic weapons, such as the Bren and Vickers Machine Gun.

As a soldier was to learn to his cost, no provision was made for training

with "Anti Tank weapons.

The best the army could do in this field

was a two pounder Anti-tank Gun, manned by the Royal Artillery. This

weapon was, however completely outclassed by the famous Eighty-eight

Millimetre Anti-tank Gun used by the German army.

On the outbreak of war in 1939, there was a vicious implement called

"A Boyes Anti-tank Rifle", issued to Infantry Units.

When this gun was fired, however, it would

either break your shoulder with the recoil or land you flat on your

back. Needless to say that if you ever hit an armoured fighting vehicle

with this weapon, the round would bounce off. It was therefore the ambition

of every soldier to dump his weapon at the first opportunity. , .

The army attached a great deal of importance to the question of religion

and, with this fact in mind; there would be a Church Parade every Sunday

morning. Other than soldiers performing essential duties, everyone would

be detailed to attend this Parade. It would be no use trying to escape

this Parade by pretending you were an Atheist because you would still

be detailed to attend and then told to wait outside until the Service

was finished, before marching back to the Depot with the rest of the

troops. It was also true to say that this was the only Parade when you

would see troops crawling out of the woodwork, many of whom would vanish

equally as fast when the Parade was dismissed, not to be seen again

until the next Sunday.

Dress for this Parade would be your Best Uniform, White Belt, Bayonet

and Walking O Stick.

It would be a full scale parade, complete with Band and Drums, with

all the Pomp and Ceremony that only the army can present on these occasions.

All Officers would be present on this parade complete with the Adjutant

on his Horse. It must have been a sight worth seeing, because any number

of civilians would line the route in order to watch the proceedings…

During his training at the depot, the whole

outlook and bearing of a recruit would have changed sp much that even

if he was to wear civilian clothes, his upright stance and arm movement

would make him instantly recognisable as a Serving Regular Soldier.

However, there is still no doubt that, regardless

of the fact, the present day soldiers enjoy the advantages of a better

type material for their clothing and stay bright metal for their buttons

and badges, coupled with plastic type equipment, requiring very little

cleaning. The Pre-war soldier was equal if not smarter in appearance

and bearing than his present day counterpart.

It was regrettable, however, that some recruits

would not be able to accept the discipline of the regular army and would

have, "Gone Over The Wall" and deserted. If he were caught,

such a crime would result in severe punishment.

The next phase in the progress of a soldier

would be a Posting to a Regular Battalion of his Regiment and then to

undertake specialised training in Signals, Driving, etc. Who knows,

he might be offered promotion to the dizzy heights of Lance Corporal…

************************************ . .

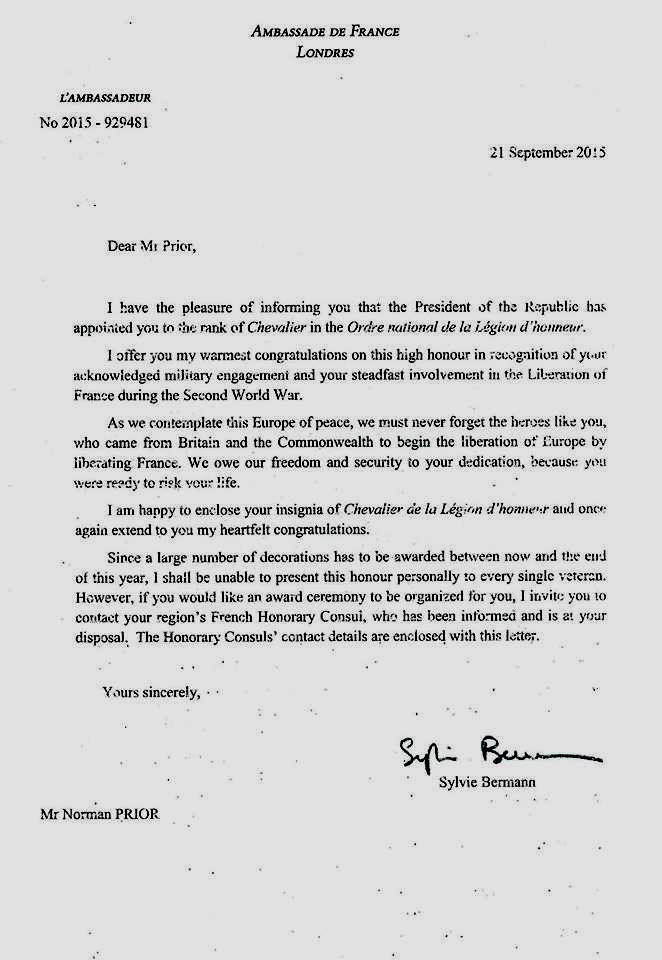

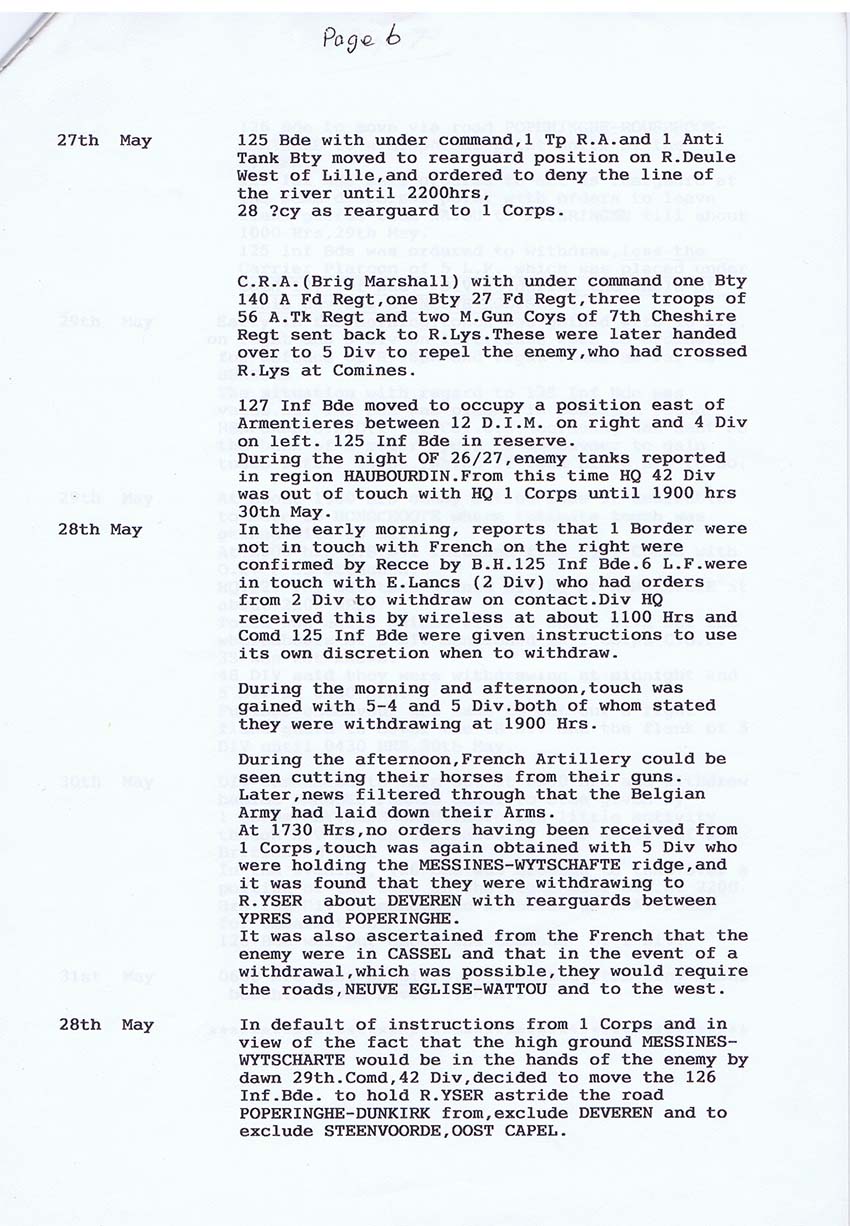

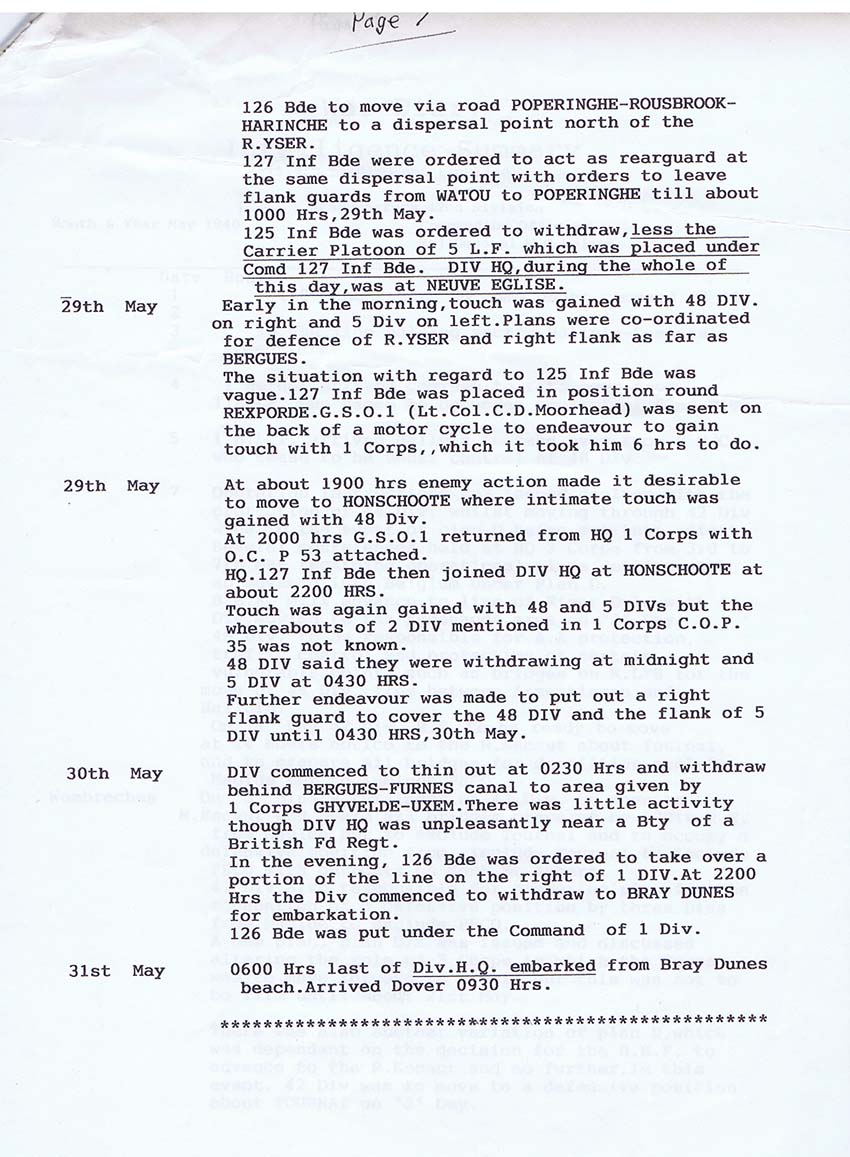

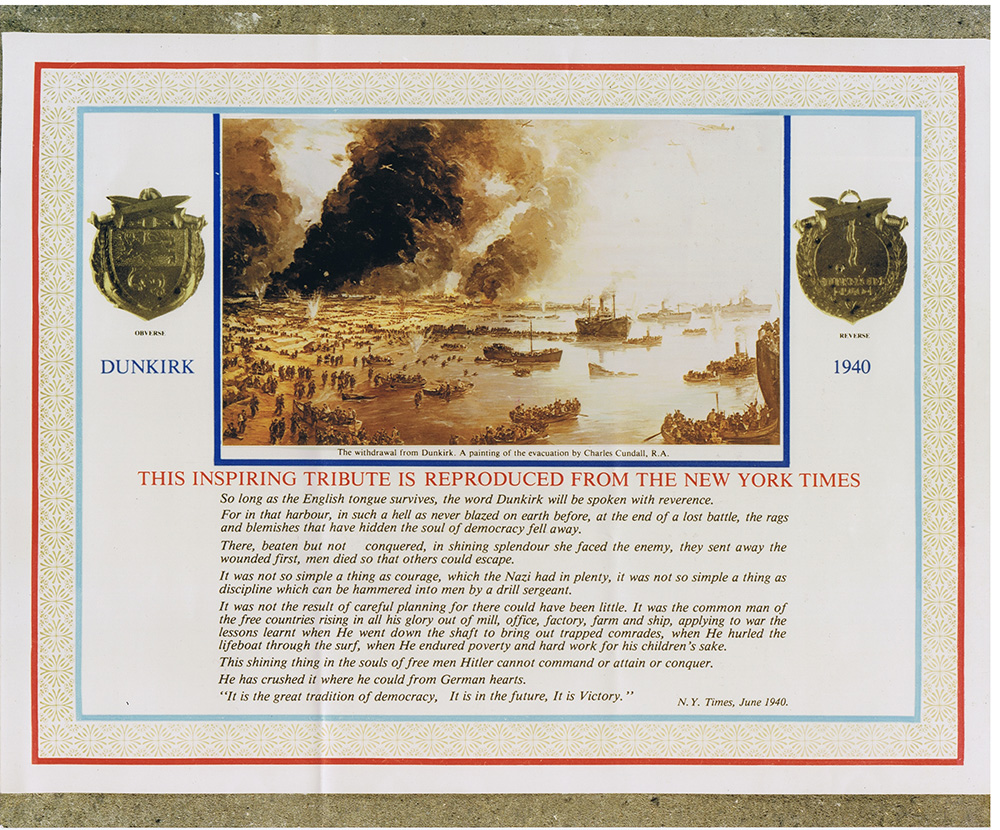

The 'victory' of the little

ships

Don Frame

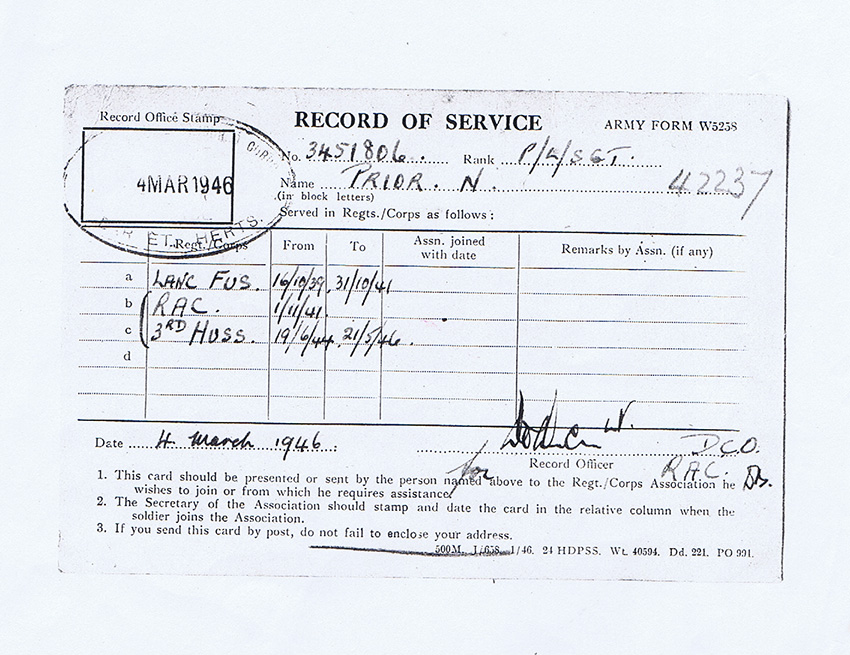

HERO: Norman Prior

Second World War.

The Victory of The Little Ships.

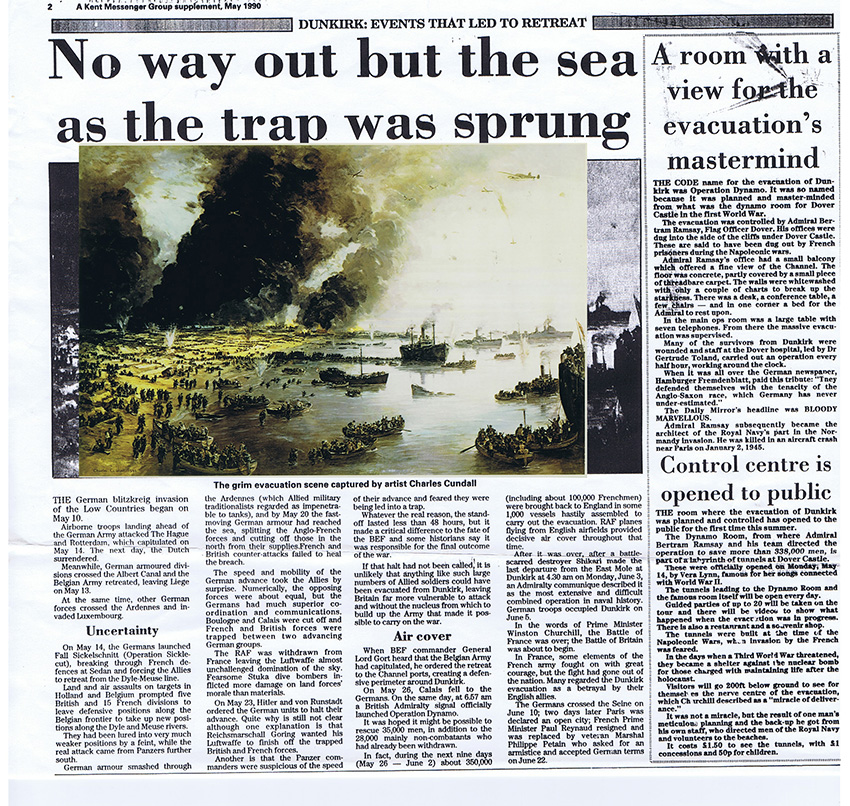

It has been described as the worst defeat

suffered by British Forces during the Second World War. But the evacuation

of Dunkirk was also something of a Miraculous Victory.

Over the course of ten days, the Royal Navy,

along with a flotilla of small vessels famously known as "the little

ships" rescued thousands of battle-weary soldiers from the French

beaches in the face of hostile fire.

By the end of Operation Dynamo - 64 years

ago tomorrow - 350,000 troops had been evacuated, enabling the Allies

to continue the war with Nazi Germany.

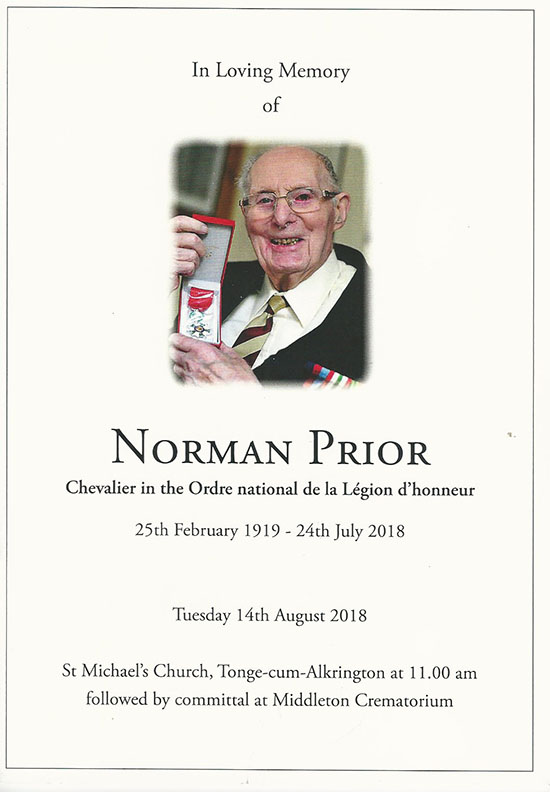

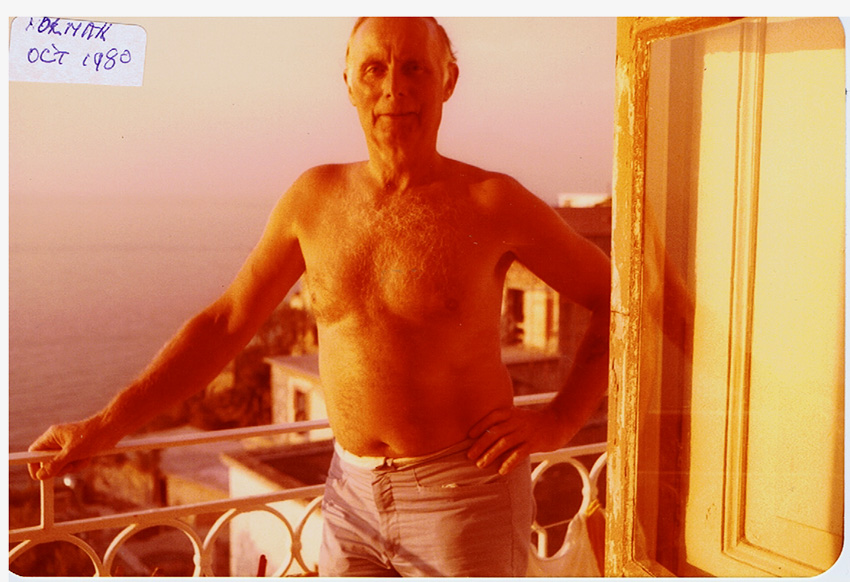

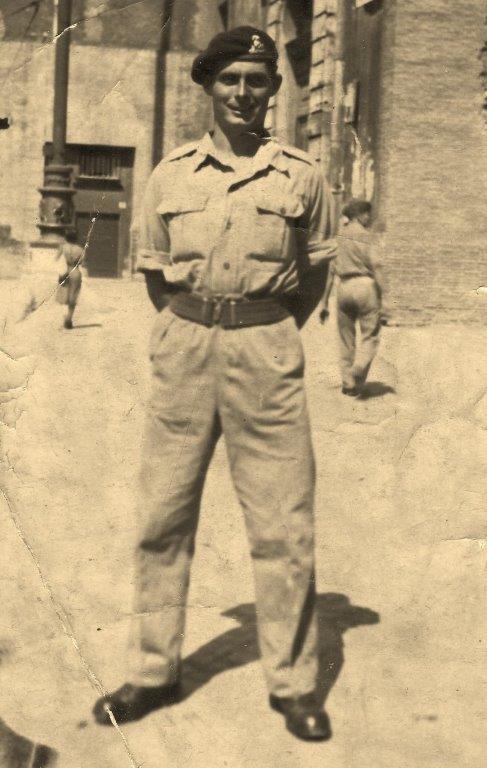

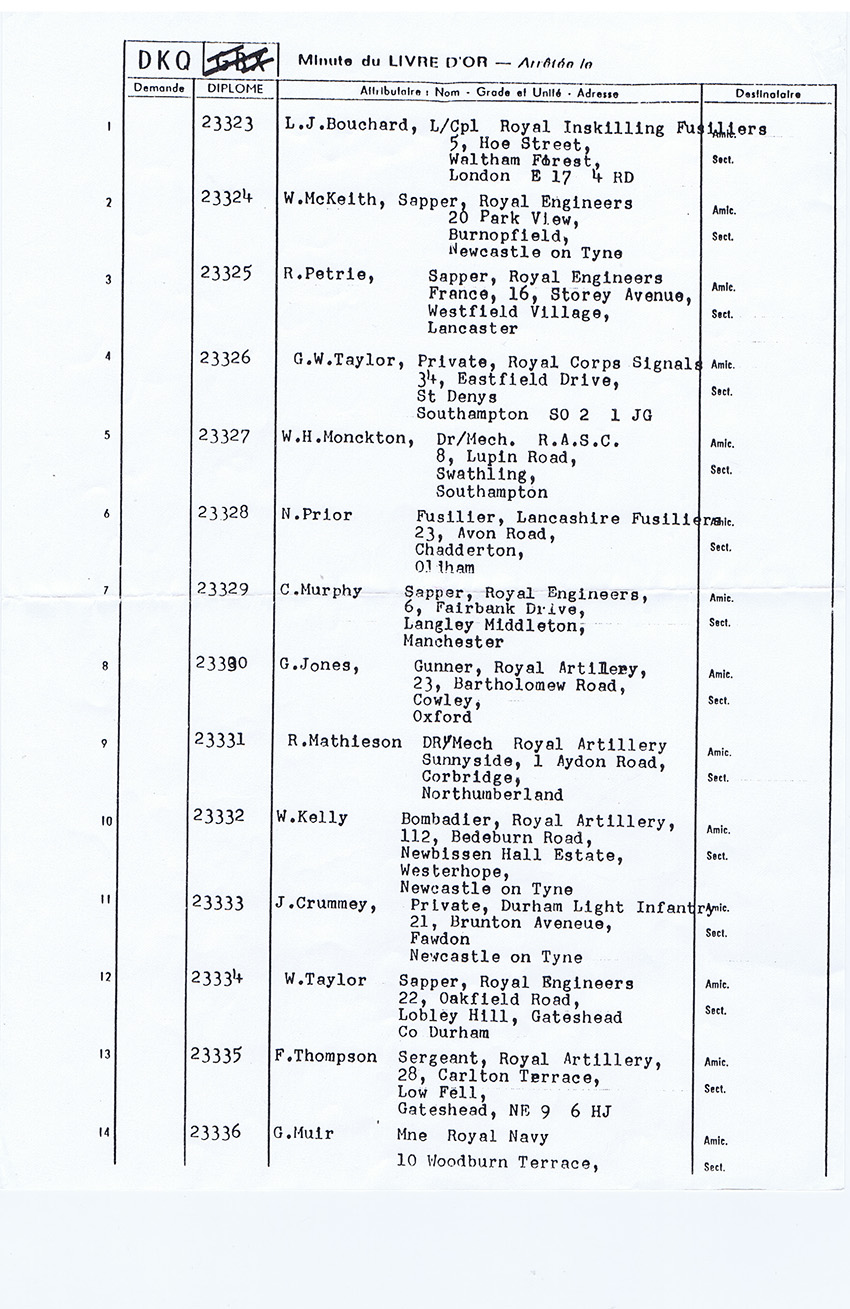

Retired works director Norman Prior, President

of the Manchester Dunkirk Veterans Association was among them. And as

the Nation remembers D-Day Norman and his comrades recall their feelings

during a week they will never forget.

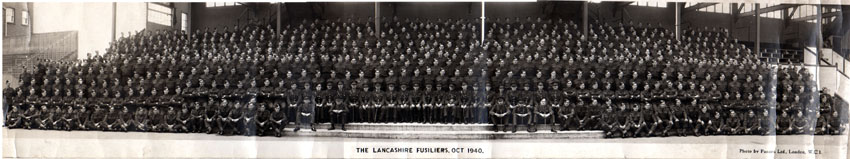

A 21-year-old fusilier with the Lancashire

Fusiliers, Norman had only been in France a little over eight weeks

when he found himself, along with tens of thousands of his comrades,

hemmed in on the beaches at Dunkirk.

"There were so many people, I never thought

I would get on a boat" he admits.

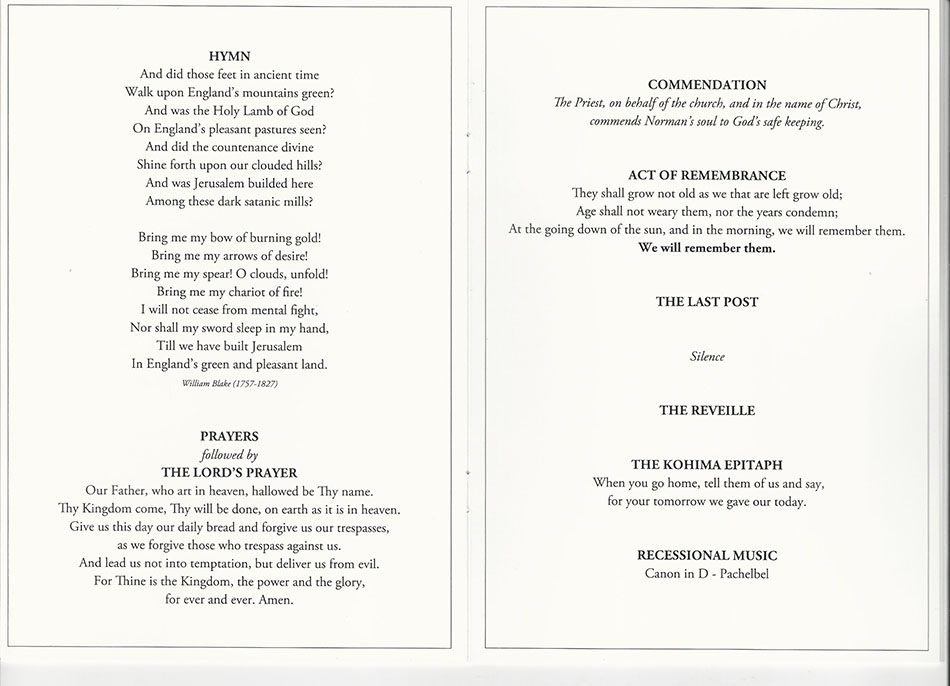

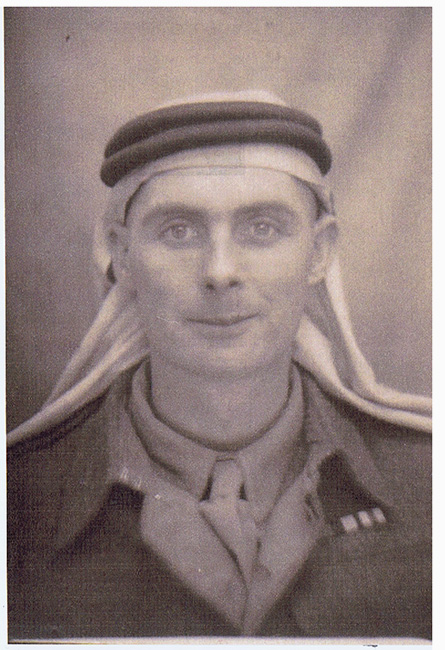

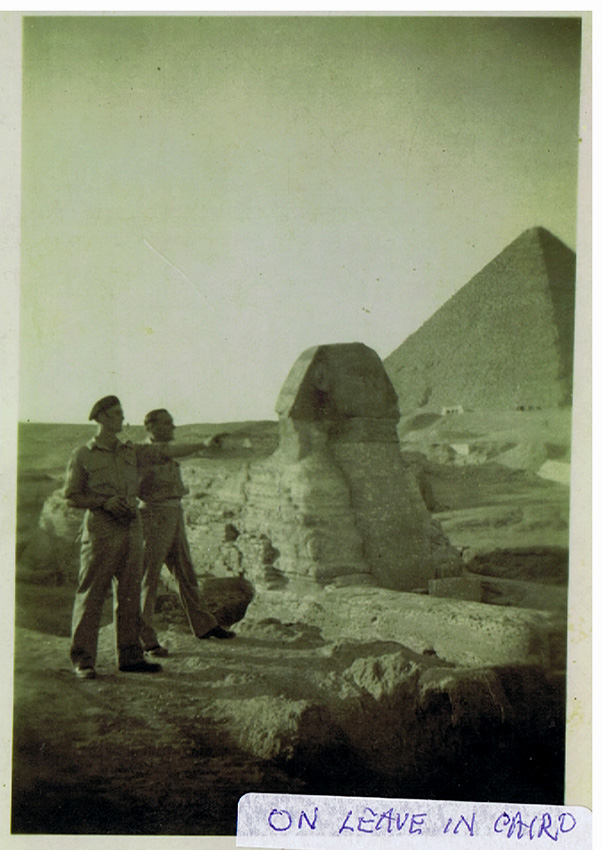

YOUNG SOLDIER: Norman in uniform

"And never for a second did I think we

would be going home. We assumed we were simply being moved further down

the coast to renew the fighting. "We lined up trucks in the water,

filled them with sandbags and then laid planks across to act as a makeshift

jetty to get the lads out into deeper water," he said.

"It wasn't too successful however, and

we got most of them away by loading the boats in the shallows then wading

out chest-deep into the sea to push them away from the beach.

"It was exhausting work, and we were

both hungry and thirsty, but we did that umpteen times." One dark

night he helped row a collapsible boat carrying a dozen men half a mile

out to sea in the hope of finding a ship to take them.

"It was back-breaking" he said.

"We hadn't a clue where we were going, but suddenly this huge black

shape materialised in front of us: a destroyer."

Now aged 84, a grandfather and great grandfather,

he recalls: "We hadn't had a square meal in days.

"I was with a Bren carrier crew in the

Fifth Battalion. We had been fighting rearguard actions across France,

and we were 30 miles outside Dunkirk when the evacuation began on May

26th.

Click on Photo to enlarge it

"Our last meal had been simple cheese

and biscuits which one of the lads managed to find on a foraging mission

at a town where we stopped."

Hear Norman Talk about the Evacuation on,

http://menmedia.co.uk/manchestereveningnews/news/s/118/118675_the_victory_of_the_little_ships.html

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Chapter 3

Arrival in Co. Durham

June 1940

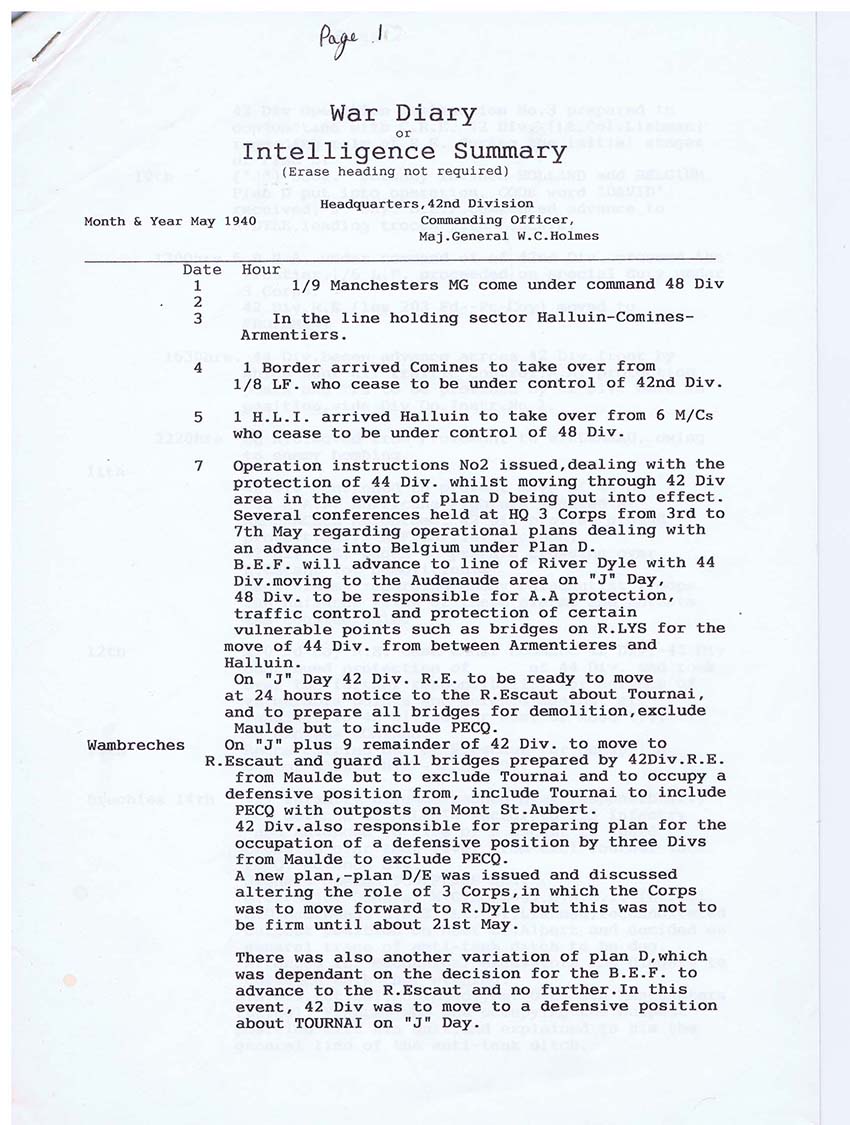

Following our return from Dunkirk and our short stay in Bristol we rejoined

the Regiment which was spread in various locations around Ushaw Moor

Co. Durham and then to Wolsingham with My Company, (HQ) in a large house

on a large estate. Harpurley Hall, with the river Wear a few hundred

yards away where some of use to a swim in the afternoon but only for

a short time as we had to move off to a new area.

The next step was to be re equipped and retrained.

My clothing was almost threadbare from our

time in France and being soaked in sea water, so a complete new set

was issued by the QM from a warehouse in Durham which we found out later

was infested with lice. Not having experienced lice before we thought

the itching was caused by the newness of the clothing and carried on

scratching.

Seventy-two hours leave was granted and a

special train lay on to the Manchester area. Early in the trip and still

suffering the itching it was quite funny to see everyone having a little

scratch. We stripped off to check but again our lack of experience led

nowhere.

When I arrived home my mother saw me having a quiet scratch and said,

have you got something on you? Of course I said no, had a meal, a good

wash and change of clothes. My mother inspected the uniform and was

shocked at the lice she found. Without further ado, she put the clothes

in a bucket and covered the lot with paraffin.

I went with Dad to the club and on our return

was invited to view the bucket of clothes which had a layer of dead

lice floating on the top. Then came the washing to remove the smell

of paraffin. When dry a lot of the colour had come out with the lice.

However, I did extend my seventy-two hours to seven days and did my

seven days "Confined to Barracks" (Jankers) as punishment.

It appeared almost everyone else had done the same.

Mid July and the next move was to Matfen Hall, Matfen, in Northumberland

on foot, Marching off at about 9-30/10pm and Marched through the night,

a distance of 38 miles with all Kit.

Matfen was a very small village with one pub and a church. Life seemed

to be dominated by Matfen Hall.

Bell Tents had been erected by the advance

party who had gone by road, and after a meal we were allowed the pleasure

of a few hours rest.

Training restarted and included practicing

rapid deployment to intercept expected German Paratroops. Coaches were

commandeered for quick movement of troops, this included embossing and

debussing in the fastest possible time.

Night Guards included "Lookouts" from the Clock Tower of the

Church. This kept us awake as the clock chimed each quarter hour and

on the hour. We helped to improve the sound by hitting the church bell

with our Rifle Butt as the Hammer came down on the Bell on the hour

stroke. That made the villagers cross with us if it happened late in

the night.

I never went into the pub, just could not

afford to. One reason was that even though we had not been paid before

and during The Evacuation from Dunkirk the "Records of Accounts",

IMPRESS had not caught up with us so we could only have the basic weekly

pay and in my case, from my pay of 14 shillings per week, I allotted

7 shillings home each week which left me with only 7 shillings (35 pence).

The Carrier Platoon moved about two miles

to Great Whittington, reputed to be the original home of Tom Wittington

or was it Dick Wittington and his cat. some of us on the floor of the,

by this time, disused small Methodist school or Chapel. Others were

in the stables of a small farm across the road and where there were

facilities to house the few vehicles we had. The chapel itself was still

used for Sunday evening Service.

On the first Sunday we heard the Organ start

playing for the Service, after a quick discussion four of us went to

join them on the back row.

We were given a warm welcome and hymn books.

It was the best decision we could have made

because apart from enjoying the service we were invited by a farmer's

family to go with them for the evening meal. On arrival at the farm

we found the large kitchen table already set out with an array of home

made farm food we had not seen in a long time. They were lovely people,

helpful and generous with an invitation for the following week…

It was not to last.

2nd August we moved to the area around Newcastle.

With the Battalion spread in Throckley, Walbottle, Newburn and Heddon

on the wall.

The Carrier Platoon was in Westerhope, a small mining village with a

pub, a club and a cinema which changed the film twice each week.

Our billet was one of a semi detached house

belonging to two brothers and a sister who had a Pie making factory

in Gateshead. Their business had actually started in the house we occupied

and a very large oven, almost up to the ceiling high, was still there.

We had rations sent from the QMs store and one or other was detailed

to be the cook but again we were lucky, because each night the brothers

would return home from the factory with a tray full of pies for us.

12th September

We moved to Northallerton in North Yorkshire under canvas.

On the first Sunday, four of us went by 15cwt truck to Newcastle station

to collect two new Bren carriers and return with them to Northallerton.

On arrival back in camp, we found the main body had already left for

the railway station to put the existing Carriers on the Railway Flats

for transporting to Newbury in Berkshire because of the threat of German

Invasion. ( The German Code word, Operation Sea Lion) .

The great Invasion Scare came then, the code

name CROMWELL was received. Within a few hours the Battalion had packed

all stores and entrained for an unknown destination.

The few of the rearguard left to close the camp gave us the message

that should we arrive back before the train departed we must go and

join the other Carriers at the railway station. If we were too late

for that, we must make our own way by road to Newbury. Someone had their

wires crossed as that message was not strictly true. But who cares,

a journey so far by road sounded fine.

The two Sgts in charge of us decided that

we would travel via Bury and Ramsbottom where most of the crew lived.

During the journey, the Ford V8 engine of one Carrier stopped and we

realised that we would have to switch over to the reserve fuel tank.

It would not start so the Sgt decided to "Prime it by putting some

petrol down the carburettor, Some petrol was spilled and the engine

caught fire, from a short from the Spark Plug, fortunately the fire

extinguishers were effective and we were soon on our way again. We arrived

in Bury early on the Monday morning and I was instructed to have a few

days at home outside Wigan and I would be picked up on Wednesday about

5pm.This was too good to miss.

They duly arrived on time , Stayed for about

an hour drinking, chatting and we gave the children rides on the Carriers.

Demonstrating the capability of both the carriers and the drivers.

We set off on our journey to Newbury complete with sandwiches and beer.

The journey was quite eventful when one carrier

ran out of fuel and the other carrier found an army depot and succeeded

in obtaining a two gallon can of petrol but the Sgt had to stay behind

as hostage until the petrol can was returned.

Air raids were encountered as we travelled through the Midlands but

nothing serious.

15th Sept 1940

On arrival on Newbury racecourse, the Sgts were called into the C.O.s

Office to give an account of what had happened. One Sgt was reduced

to Corporal and the rest of us back to normal duties.

The visit to Newbury in September was much more enjoyable than in Jan

1940 during the big freeze. Our billet was under the Grand Stand, still

on the floor. Was much more comfortable than the freezing horse boxes

we occupied on our previous visit.

Our roll was to prepare for the expected German invasion. (Operation

Sealion), so everyone was on full alert.

We spent a few happy months here until the

whole of the 42nd Division's next move in November, to East Anglia on

coastal defence with the Battalion spread out in Southwold, Walberswick,

Dunwich, Bulcamp and Halesworth. The 1/5 Battalion were in Southwold

in Suffolk where the Duke of York's Annual Camp for boys was previously

held.

Battalion HQ was at St Felix School for Young

Ladies. There were no young ladies there then of course as most of the

population had been evacuated. The QM's Stores was at Bulcamp, (In the

Workhouse) along with the Carrier Platoon. The Rifle Companies were

based along the coast at Southwold, Walberswick and Dunwich.

This was an ideal situation for the Carrier

Platoon who at night time was responsible for Guard Duties. The cookhouse

acted as Guard Room and it was next to the QM's Store so it was an easy

matter to break into the QM's store to get extra rations during the

night and have a Fry Up between spells on guard. (Two hours on, four

hours off.)

All our moves were for Home or Coastal Defence

so it was always important to be at state of alert and ready to move

at a moments notice.

In all cases the beaches were mined and barbed

wire entanglements in place except for designated places left clear

for access.

We stayed there until the End of February 1941 then moved to Roman Way

Camp near Colchester. This was well equipped with new wooden huts built

originally for the Militia in 1939.

It had a very large Square for Parades and garages around the perimeter

where we were able to do maintenance on the carriers and trucks.

In May 1941 we moved again, this time to Clacton

on Sea in Essex. Again on Coastal Defence. The night before we arrived

there was a heavy air raid but everywhere was fairly peaceful during

our stay.

The Billets were very good .Most of the troops were in evacuated Boarding

Houses on the sea front.

Commandeered by the Army

The Carrier platoon billeted in a house which had been evacuated. A

large civilian garage was also vacant so was used for the Bren Carriers.

For PT one morning, someone had the bright idea of going into the sea

for a swim, after all it was May.

We wended our way through the gaps in the barbed wire defences onto

the sands and all made a dash into the sea. We came out faster than

we went in. It was ice cold so we returned to the billet quickly to

get warmed up. Back to PT.

It wasn't to last, in June 1941 after only

a month there the Battalion moved to a place called " Duke's Ride"

,near Thetford, Norfolk. We were under canvas over a dry pit about three

feet deep, in a large forest. miles from anywhere. This was another

of those out of the way places that the army were good at finding.

The weather was very hot and dry; everything

was covered in a thick layer of dust. It was an ideal training area

and we worked very hard but that dust was everywhere,. Yet there was

one respite. Each morning a number of Land Army Girls from a Hostel

a few miles away would pass the camp in trucks on their way to farms

or forestry duties. As they came by they started throwing things at

the troops who in turn would make sure they got them back the following

day. That broke the monotony a little.

But with the Carrier Platoon we could usually

find an excuse to break the monotony by taking the carriers out for

driving instruction of non drivers.

One Friday afternoon while driving along,

two Land Army Girls were on the roadside trying to hitch a ride to Bury

St Edmunds railway station. Of course it was not allowed but after a

short discussion and a bit of pleading from the girls we agreed. After

about two miles we were overtaken by a vehicle which stopped in front

of us and woe and behold, out stepped the Adjutant from our own Unit

on his way to the station, going on a weekend leave.

He ordered the girls out and gave us a severe

talking to with the promise we would hear more. We were up for "Orders"

on the Tuesday morning

This is where the fun comes in. In the army they have this rule that

in the absence of an NCO, the Senior Soldier takes responsibility.

Fortunately for me as the driver and in control

of the Carrier the same with the other carrier driver we each had a

longer serving soldier who each had served in the TA, and were deemed

responsible for allowing civilians to be carried without permission.

We argued this, knowing it was a bit unfair and saying we thought that

being Land Army, they were classed the same as us but that excuse did

not wash so two trainee drivers under instruction received seven days

each, confined to camp. It was really a most unfair decision but it

did have its funny side. One of them, Jimmy Dentith nearly cried. It

was his first offence. Until that time he had had a clean record.

Even in the worst situation troops always

make the best of it and find something to keep them amused and the mind

occupied.

It was not long before we were on the move

again .We stayed until July before going to Long Melford and Sudbury

in Suffolk where we celebrated "Minden Day"1941.

This move coincided with the War Weapons Week in Sudbury where funds

were being raised for the war effort. We enjoyed the week giving help

and support and lots of rides on the Carriers for the locals. This was

very much appreciated by everyone. Especially the children.

At the end of August 1941 we moved to Colchester

again, this time to Le Cateau Barracks. Wherever the troops go, training

continues but in the barracks an additional stint was Fire Drill with

the barracks own fire fighting equipment. This was a nice change and

something else to learn about and of course it was always easy to make

sure the hose slipped and gave someone a soaking. All taken in good

part.

Between these dates I attended an advanced

course in Leeds on the latest Tanks, this was for only two weeks but

was followed shortly afterwards by a few weeks course in Eastern Command

REME Workshops. The Instructors decided that my engineering skills and

knowledge could be put to better use and made me an Instructor for the

rest of my time with them.

Before leaving them to return to my Unit

I was asked if I would transfer to REME. and backed that up with a letter

to my Unit to that effect. I said I would consider it.

On my return, I was called into the Office

and pointed out to me the advantages of staying with my Unit and the

increase in pay I could expect as we changed over completely to a Tank

Regiment. I agreed to stay. I realised later that promotion would have

been higher and quicker in REME but I had not realised that at the time.

I had made my choice and I don't regret it because I stayed with comrades

I knew and the later training was valuable in my civilian work after

coming out of the Army..

It was at this time, October 1941 that the

War Office decided that the 42nd Infantry Division of which we were

a part, would be changed over to an Armoured Division.

Training for this began by selecting personnel

for the various new roles. Such as tank driver /mechanics. Wireless

Operator/Gunners etc. Everyone had to be reclassified under all the

different headings and jobs to which they were most suited. Each man

had to be skilled in more than one job.

Anyone not happy with the new role were given

the opportunity to stay as Infantry but join other Regiments or where

possible go to one of their Regiment's other Battalions.

I was quite happy and looking forward to the change. Some men were sent

down to Bovington and Lulworth, some to Farnborough, places which were

established Schools for armoured fighting vehicle training.

I was selected to go to Martin Walters of

Folkestone. International Coach Builders and Motor Engineers for three

and a half months on a Vehicle Mechanics Course along with another man,

Ernie Ramsbottom from Heywood, who was from the Transport Section and

me from the Bren Carrier Platoon?

We were given rations and travel warrants

and travelled down from Colchester, through London threading our way

through loads of fire brigade hose pipe,carrying all our equipment as

bombing had taken its toll. Then by Southern Railway to the home of

Mrs Reynolds of 64 Morehall Avenue in Folkestone. Mr and Mrs Reynolds

were nice people with a son in the RAF and a daughter; a nurse in Canterbury,

then Betty who was the youngest and worked in the local grocer's shop.

Perhaps by working in the local shop a few extras would become available.

We met up with men from other Units of the Division who made up the

small class numbers.

This was almost home from home, working at

Martin Walters during the day and doing lots of homework at night ready

for the following day.

But it was very valuable learning from experts. Some of them were Professors

in the chosen subjects.

It was very rewarding training which would be useful later in life.

Occasionally we would go to the cinema and

call at a café for supper afterwards. Being in a vulnerable area,

the café's seemed to have more rations available than some places

we had served in.

Small Sprats from the local fishermen came

up regularly in Mrs Reynolds household as did a Hare or half a Hare.

On those occasions it was important to be aware of lead pellets in the

flesh; there would be a little pile of these on the edge of each plate.

Lunch was taken in the Martin Walter's canteen

and was free to us.

Sometimes at weekends we would do our turn

at Fire Watch against air raids plus if one of the workers wanted to

miss their turn at fire watching they would offer us about five shillings

which to us was a good pick up.

The works closed for Xmas so I was able to

go home for a few days after which it was back to work.

Eventually the three and a half months training finished we returned

to our Units, our reports and results sent to the Units separately.

By this time our Unit had moved to Barnard

Castle Co. Durham so that was our destination.

This was a new camp of wooden huts, still under construction with mud

everywhere, but this is where we would try out our new found skills.

On the moors was the Battle Training Area where live ammunition was

used. It added a bit more excitement into training.

I had only spent about three weeks there with

the Unit and of that I had 10 days leave due. On my return from Leave,

I learned that because of the excellent results I had received from

Martin Walters of Folkestone I was to go to Tom Garners, Motor Engineers

of Manchester, but we were based at Knott Mill in the Deansgate area.

This was an Upgrading Course and would last Eight Weeks.

This was an opportunity not to be missed

We were billeted in a house in Raby Street,

Moss Side in Manchester and even though meals etc were provided by the

owner we had Sergeant Mathias in charge to keep everything up to army

standards and Discipline and of course to march us to the works each

morning.

After four weeks and complaints about the food we moved to Acker Street

not far from Manchester Royal Infirmary where Actors appearing at theatres

in Manchester would stay. Here the food was much better.

We made many new friends among the other trainees and one, Dennis, and

I went out on the Saturday night to Belle Vue Speedway and afterwards

around the other leisure areas including the dance hall. I was not a

dancer but Dennis being a typical cockney soon made himself known to

two girls, Elizabeth and Edna with whom we struck up a friendship.

As the buses were not always reliable and

it was late, Dennis, being the hero of the hour volunteered that we

would walk with them from Belle Vie to Rochdale Road so they could catch

the all night bus service to Middleton. This we did, saw them safely

onto the no17 bus and then made the long journey back to Moss Side and

our Billets.

We arranged to meet and go to the pictures

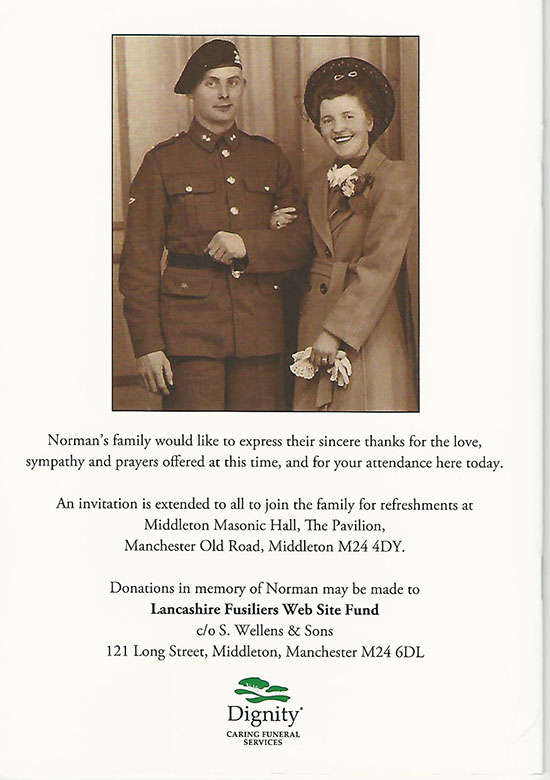

on the Tuesday night in Manchester. Elizabeth and I carried on the relationship

and a year later we were married. The best decision I ever made, thanks

to Dennis who was probably more outgoing than me.

I never met him again after the end of the training.

Our Love and our marriage and the happiness we share have stood the

test of time including by celebrating our Diamond Wedding.

We were very fortunate that no serious accidents

occurred during this period where men were learning to drive tanks.

Not that it was all trouble free. The road from camp to the village

of Staindrop was a good long stretch and many learned to drive there.

One tank had the misfortune to veer off the road at one point and went

straight into one of about four houses which were luckily unoccupied

at the time. A few days later and another learner driver did the same,

fortunately without casualties.

The 125 Brigade of 42nd Infantry Division

now became the 108 RAC. of 10th Independent Armoured Brigade of 42nd

Division.

Now it was time for another move, this time to Rufford Abbey, Edwinstowe,

Near Worksop, and Nottinghamshire. Of course this was Robin Hood country

with the "Major Oak Tree " that would easily hold two or three

men.

An area known as The Dukeries, consisting

of Welbeck Abbey, Rufford Abbey and Thoresby Hall, a lovely area where

during that summer in addition to our army duties we were called upon

to help out the local farmers harvest the Flax which had to be cut by

using scythes etc.

After training so many troops into tank crews

the War Office decided that 108 RAC and 10th Independent Armoured Brigade

were now longer required. After Hundreds of men had been trained and

sent abroad to join various armoured regiments the Brigade was to be

disbanded. This was a sad blow for everyone but the decision could not

be changed.

The 10th Armoured Brigade went up to North

Yorkshire to be disbanded. This took some time The 108 Regiment RAC

was stationed at Wensleydale and Middleham,

near Leyburn.All the equipment was handed over and postings instructions

were issued to everyone

Embarkation Leave was granted and on return and along with many others

went by train to Glasgow for the move abroad…

This took some time and the remaining troops posted abroad.

But first all the vehicles, tanks trucks, stores etc. had to be handed

over to various depots.

We boarded the ship whose name I don't remember

and sailed out past Northern Ireland in convoy into the Atlantic, zigzagging

our way south. The sea was rough; some men were out of circulation for

several days. That didn't matter to the rest of because we got their

rations as well as our own.

We saw a few depth charges being discharged into the sea and the explosions

that followed.

Eventually we turned east into the Mediterranean

Sea and docked at the Port of Algiers then south to the dirty, dusty,

little town of BLIDA.

Under canvas once again.

After a short stay there, we went to the outskirts

of Algiers for a few days before boarding a train which had no windows;

the seats were just wooden slats. From the outside.apart from the lack

of windows we looked quite normal.

This was quite a long journey with frequent

stops for the engine to fill up with water etc… At each stop a

crowd of tribes people would come charging from the hilly areas begging

for whatever we could give them.

These people were obviously very poor, their

clothes were just rags really and the food must have been very scarce.

The strange thing was that they all knew the words biscuit and cigarette.

When the train set off again they would disperse.

We travelled through many tunnels and the

smoke from the engine filled the carriages so that we were gasping for

breath and glad to reach fresh air again.

We eventually arrived at our destination which

was the dirty little village of

El Guerra about thirty miles from Constantine.

Apart from the police station and several houses, most of the rest of

the inhabitants lived in huts made from any bits and pieces they could

find including old tins, opened out to cover the roof. Some had bits

of rag or hessian covering the roof which was only about feet high.

Or less.

We had search lights in watch towers to assist

us on guard duty against the thieves who prowled at night time. Thieves

who could take your blankets while you slept leaving you to waken up

shivering and wondering what had happened.

Away from the camp entrance but on the pavement

was a man with a mobile charcoal burner cooking Kebabs. The meat on

the skewers was really an apology for meet, something the average person

wouldn't look twice at. To walk past it meant a step into the road and

at that moment a battered old car came passed and hit a soldier, knocked

him to the ground leaving him with a deep wound to the side of his head.

The car didn't stop so we returned the man to camp for treatment. He

went to hospital and we never saw him again.

Training never stops of course and in my case

I attended a Course on the General Motors Two Stroke Diesel engines

as fitted in the Sherman Tank. These diesel engines replaced the original

petrol engines which were so prone to catching fire. The Course lasted

eight weeks and was equal to a City & Guilds qualification. As with

other Courses I passed with flying colours.

The knowledge gained was so valuable and so necessary in a Tank Regiment.

The camp was close to the Atlas Mountains

and the weather was atrocious with snow at night melting during the

day and making the ground into a quagmire, so much so that in the whole

of the war years it was the only time we ever received a Rum ration

and had a spare pair of boots issued. One pair worn while the other

pair was drying around a slow combustion stove made from a 40 gallon

oil drum and burning wood from trees which had been cut down by the

troops.. This was housed in a special wooden hut.

It was also the only place that a supper was

available to combat the cold and damp. This was always cheese melted

into a liquid and a thick slice of bread to dip in it.

The lumberjack team was a Fatigue Party, detailed each morning for the

Job.

Mid morning we were issued with half a large cup of delicious Dates

which were very welcome.

Our camp was part of a larger one with one

part for British and the other for Canadians and they too had their

own Tanks and parking area. .

Each week a ration of two bottles of Canadian beer arrived, The Canadians

had a similar ration and would come offering to buy ours at a good price.

Quite a few did sell.

The Order came for a move to Italy, one we

were looking forward to and we watched the Eruption of Mount Vesuvius

spewing out flames and red hot ash, then onward through Caserta (a US

Main Depot,) Avelino, Benevanto etc and ended up in the Apennines.

Our equipment had gone astray including blankets

etc, so we were each given a two man Bivouac which appeared to be made

of rigid sail, cloth to keep out the freezing cold but they were almost

useless.without our blankets.

What a terribly cold night it was, Needless to say, we were up most

of the night walking and jumping about trying to keep warm.

The following day our kit was located and returned to us.

Volunteers were called for to assist in the cookhouse. This was one

job not to be missed, with the possibility of getting extra rations.

I found that food was available and in reasonable quantities but up

to that time was being ruined by over cooking and lack of care on the

part of the cook.

In spite of the fact that we were so isolated, poor ragged Italians

came at meal times begging for food and even when the troops had thrown

any scraps into the 40 gallon waste bin there was a scramble by the

Italians to retrieve it and where possible intercept it before it dropped

in the bin. Then we realised their plight and handed it to them.

Soon we were on our way down to lower ground where it was much warmer.

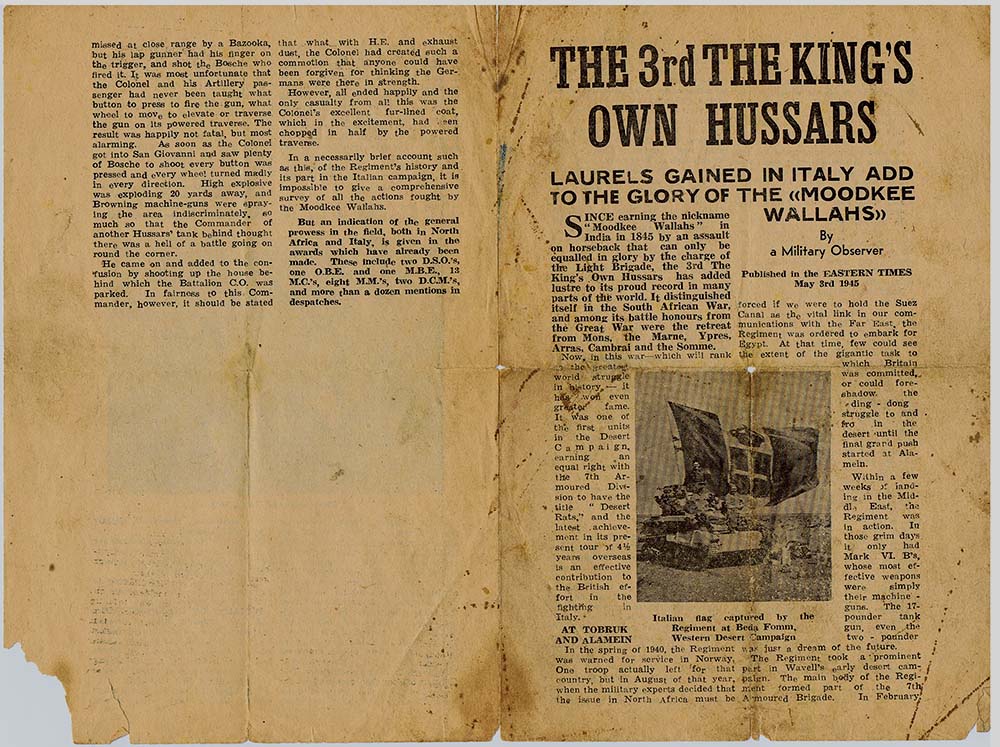

We set up camp where we became a Reinforcement Unit with three tanks

with Captain Riley of 3rd The Kings Own Hussars in Command and me as

his tank driver.

Our roll was to replace casualties in the Regiment and prepare for the

attack at Cassino. We watched the bombers doing their part but our roll

was to await the Breakout from Cassino and continue the assault from

Cassino and through the Leri Valley towards Rome but there was much

fighting to be done before reaching Rome.

.

. The only practical approach to the city was via the Liri Valley but

that road was still blocked by the town of Monte Cassino with the Benedictine

Monastery on top. This was known as the Gustav Line. A great defensive

position for the Germans to see everything for miles around.

The Allies had tried three times in terrible weather, during the first

three months of 1944 to break through the Gustav Line without success

but with heavy losses in manpower.

Behind Monte Cassino was the Adolph Hitler

line constructed across the Liri valley. Behind that the Allies had

made a landing at Anzio.

On May 11 the Allies began the final phase of the battle for Rome By

the 18th May the town of Cassino had been cleared of the enemy and the

Poles had raised their Flag on the ruins of the monastery.

The 3rd Hussars went into action at Coldragone

Wood Nr Arce

It was here we had our first casualties on the approach march from Cassino

when HQ Reconnaissance Tank was blown upside down on hidden pile of

Teller Mines. The crew of four were killed and Col. Farquar was badly

burned when he tried to drag their bodies from the blazing tank.Another

officer Lt Ashworth was wounded when he put his hand on a pencil mine.

During the next two days the 3rd KOH were

ordered acoss the Liri river to join the 78th Division near Ceprano.

More than 100 Germans were killed and twenty-six taken prisoner for

the loss of one Infantry man

4th June. Rome fell and two days later we drove through the eastern

suburbs on our advance north. It was disappointing not being allowed

to stop in the city.

News came through on the 6th on the Allied landing in Normandy.

The enemy retreated until third week of June

when they made a stand about 100 miles north of Rome east and west near

Lake Trasimino.

Battles were fought at Civita Castellana,

Gallesi Castiglioni, and Orvieto which was only twenty miles south of

Lake Trasimino where Kesselring had rallied his forces. The resistance

was much tougher, the opponents were the Elite German Paratroops who

had orders to hold the line at all costs.

Progress was slow due to the numerous craters and concrete road blocks

covered by concealed anti tank guns and Bazookas. Ficule was taken on

15th. Capt Riley, I had been his driver, was killed while leading the

advance north of the village and at Montelenone on the 16th, two tanks

were "Brewed Up" by Bazookas but no further casualties.

We reached Citta dalla Pieve at dusk on 16th June but it was too late

to attack so pulled back to laager, leaving the East Surrey Regt to

keep watch.

9th Armoured Brigade Headquarters were confident that the defenders,

reported to be a Battalion and a Half of German paratroops would withdraw

during the night and one squadron would support an attack by East Surreys

at first light.

But far from withdrawing the enemy were strongly reinforced. "A"

squadron paid a heavy price for this misfortune.

We started off up the road and met only small

arms and mortor fire but as soon as we entered the narrow streets of

the town, hidden anti tank guns and bazookas opened up from every side.

The Hussars Tanks fought back as best they could in the confined space,

but lost four tanks with five men killed and ten wounded before the

Royal Wiltshire Yeomanry were sent to take over..

From this action where much bravery was shown

there, where awards were made.

P l Jarmaine of "A" Squadron was mentioned in despatches after

taking care of the wounded and hiding wounded comrades in the basement

of a house for two nights and a day.

Later on 16th the Regiment was withdrawn five

miles, back to the village of Santa Maria and visited by the Divisional

Commander Mjr, Gen Keightly.Here he consoled them for their losses and

praised them for the confidence and inspiration they had inspired in

the infantry battalions of the 78th Division to whom they had shown

they had the gallantry and dash to defeat the enemy at every turn.

We rested up at Santa Maria during forty-eight

hours of constant rain.

For their part in fighting the German paratroops from Orvieto to Citta

Della Pieve, the 3rd Hussars were awarded their first battle honour

of the Italian campaign.

The next action, at Ripa Ridge, a few miles

east of Perugia, was equally deserving more battle honours, for it was

there that great courage was shown but it was also a feat of tactics

that was reported to be unique in Armoured Corps history.

Ripa Ridge, five miles long and rising to 1,000 feet, marks the beginning

of the rugged, mountainous country between the river Tiber and Chiasco

river.

From the top and its steep slopes to the north,

the Germans, heavily dug in, cotrolled the approaches to the main road

running along the left bank of the Tiber to Umbertide.

Opposite them was the 17th Infantry Brigade of the 8th Indian Division,

who on 18th June began a series of sharp actions that secured Ripa but

failed to drive the Germans from the higher ground beyond .Even the

gallant Ghurkhas had to fall back due to the fierce artillery fire and

the Brigade's casualties were heavy.

That was the situation on 22nd June when the 3rd Hussars and The Chestnut

troop of RHA, after fording the river in darkness with tanks and guns,

joined the 17th Brigade to support another attempt to open up the Umbertide

road.

The key was to advance and attack a steep

hill, point 450 on the right front which the Regiments predecessors,the

North Irish Horse had failed to do and said it was a tank obstacle and

impossible to ascend.

Sir Peter Farquar,CO 3rd Hussars was more confident. After flying over

the ground in a Spotter plane with Mjr Bell of "B" Squadron

he was sure the tanks could find a way up

The 8th Indian Division were reluctant to

risk further casualties so the Corps Commander agreed to allow the 3rd

to make the raid alone, supported by the Divisional Artillery to draw

the enemy fire and gain information

It was a great success. As "A" Squadron

was moving forward under a bombardment .The Germans were taken by complete

surprise and withdrew in disorder, believing their line was broken and

they were almost surrounded..The enemy were pushed back five miles at

no cost except for a random shell which landed in "C" Squadron

B Echelon area, and sadly killed SQMS Dixon.and Cpl Sellars and wounded

four other men.

The 3rd counted their bag; 11 guns and many

vehicles destroyed, three bazookas and one Field gun and Field kitchen

captured, at least one hundred Germans killed and sixty taken prisoner.

More Italy and beyond

Later, as we were moving forward and we were ambushed and came under

heavy fire, George Needham driving the three ton B Echelon Truck with

Sgt Parsons along side him in the Cab and L/Cpl Dixon and me sitting

at the front of the bodywork with the Tarpaulin Cover tied back to get

a free flow of air through. Dixon was on the left, me on the right,

chatting and enjoying the fresh air and sunshine as the short, sharp

attack started. And all hell let loose.

Dixon was hit on the side of his head with

a lump of shrapnel. George worked frantically to drive the truck out

of trouble as I dressed Dixon's wounds . We cleared the area and took

Dixon to a Casualty Clearing Station (CCS) we had passed earlier, from

there he would be taken hospital. I don't know if he survived.

We continued forward through many hazards and always prepared for the

worst.

We fought our way North to Florence but further progress was halted

as Winter approached and the winding, rising roads were similar to going

over the Alps so were not considered suitable for tank

warfare at that time . Instead we were moved over to the Adriatic. side

We had received an allotment of Valentine

Amphibious Tanks. These were only three men Crew. Driver, Wireless Operator

/Gunner and Tank Commander. We Trained in these on Lake Bracciano with

very tight security for an intended assault across the wide stretch

of the river PO on the Adriatic Front.

with Headquarters Squadron in Senigalia with "A" Squadron,

my Squadron in Brunetto.

One night during the training where we were

to make a landing on the other side of the large lake, The

Vertical air tubes which supported canvas surround which enabled the

tank to float, had to be inflated. and steel strips fell into place

and locked in position. This took approximately four and a half minutes.

On reaching the landing zone the canvas supports

were deflated, this only took about four seconds.

Unfortunately, half way across the lake, the canvas of one tank somehow

deflated, the driver and wireless operator were trapped as the tank

sank in seconds, never to be seen again and it was assumed it was in

volcanic ash as the Lake was the result of a Volcanic Eruption from

hundreds of years before.

Each tank was fitted with a Bouy which remained on the surface in such

accidents. It was said it was too deep for divers and In daylight a

Spotter Plane flew over but could not see anything. Such bad luck.

A few days later, the two black and bloated bodies surfaced. These were

buried at the lake side.

I

In time for Christmas. I was now a Corporal and,in a Three Ton truck,

I went with two Troopers and Lt Thawnton in Charge to lay signs to act

as decoys in the Faenza and Forli areas south of Bologna, to give the

impression that a large Force was being assembled for an assault on

the German Lines. We drew enough Rations from the area QMs Stores which

had some Italians employed there to make it all real .

Then came the news that men who had served

four years abroad were being sent home on the Python and Liap scheme.

(Leave in addition to Python).

As the 3rd Hussars had been in the Middle East since August 1940 and

there were up to Seventy in number. involved It meant the Regiment would

have to be reinforced from other Regiments. and retrained.

This was completed but we did not get the

chance to continue, instead we left our comrades who were going home

and went South by road to Taranto in the foot of Italy. From Italy,

next stop the Middle East.

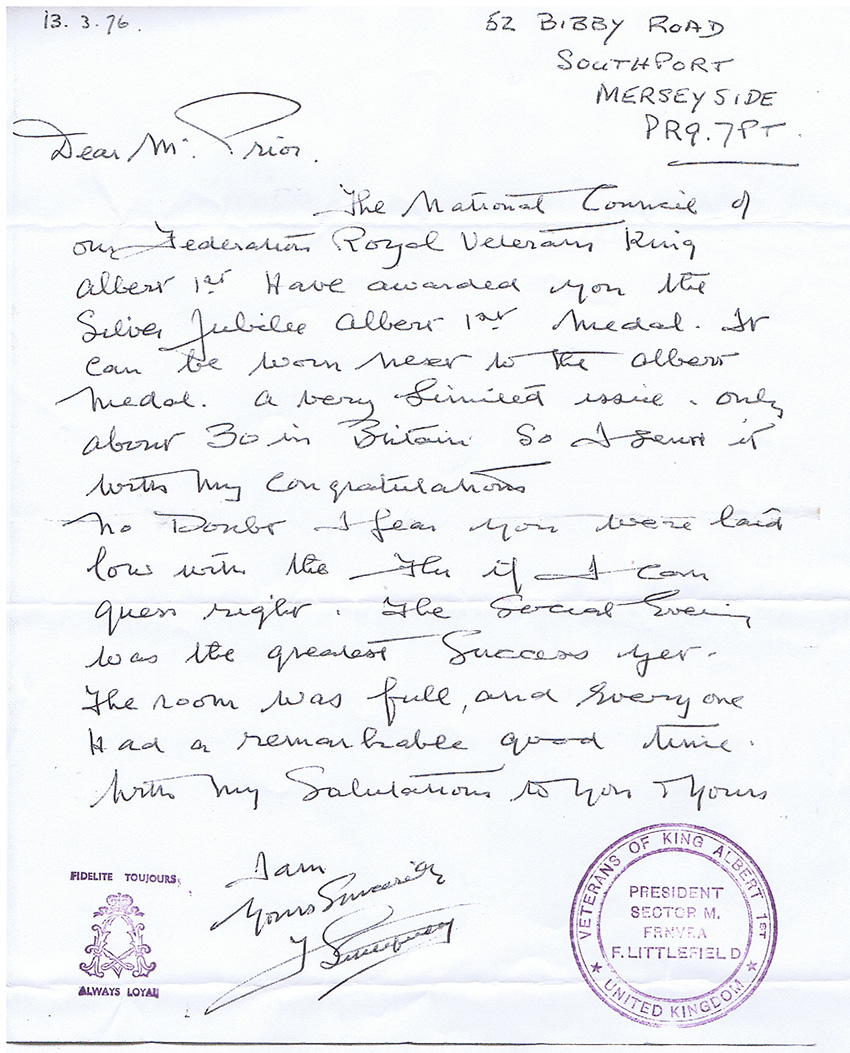

We travelled by road from Senegal on the Adriatic Coast down to Taranto

,the foot and after a few days in a filthy Transit Camp, boarded a ship

to Port Said, Egypt, and then across the Suez Canal and the Sanai desert

stopping at Gaza Station to fill the engine' water tank before going

to a Camp at Adloun, about eight miles south of the Capital, Beirut.

Our New Roll was Internal Security. This was to include Syria and later

Palestine.

This was peaceful and a nice change. It was right by the sea and after

daily duties we were able swim in warm calm waters. and visit Beirut

regularly by truck. During the day we visited various reported sites

that drugs were being shipped. We never found any.

We held Manoeuvres' with the Indian Brigade tanks on the Syrian Desert.

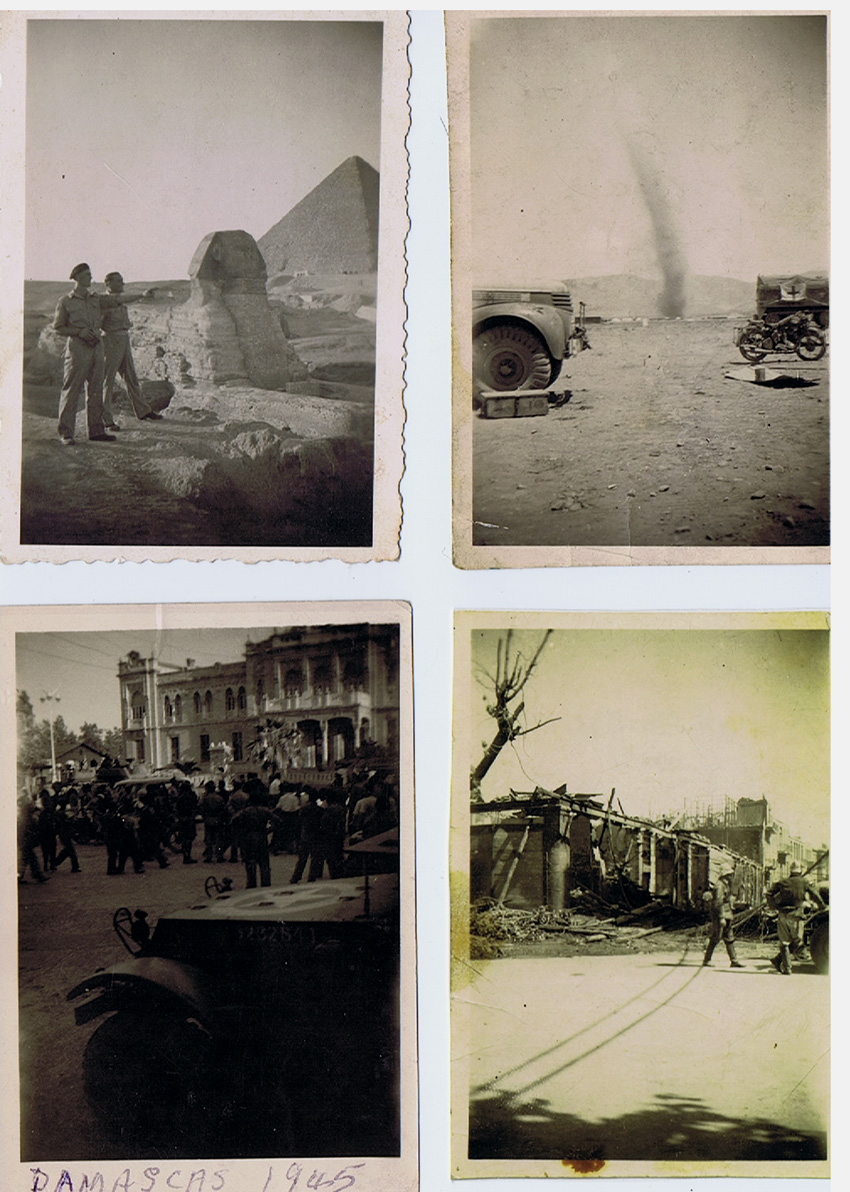

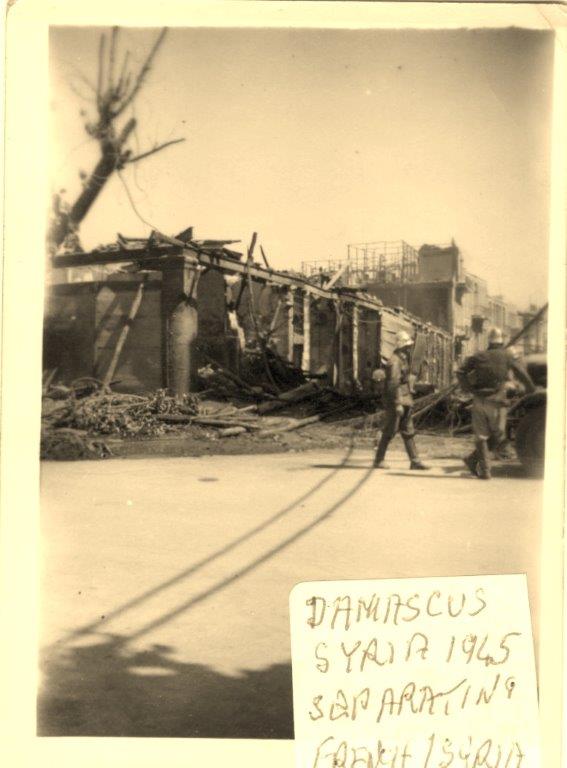

It was at this time that the uprising by the

Syrians against the French started and we moved to various places to

intervene. We made camp at Jebel Maazar a few miles from Damascus when

the Signal Sergeant fell sick with suspected Meningitis and went to

hospital We were placed in quarantine for ten days.

During this time a plague of Locusts descended . The sky was black with

them for miles . Even though we were in the middle of them, they ignored

us and stripped all the available greenery before disappearing in that

same black cloud to find new ground.. Peace at last.

It didn't last, the fighting between the French and Syrians had spread

to Damascus and the quarantine was forgotten as we received orders ordered

to intervene.

Damascus was shelled from two French Forts and strong points in the

hills bordering Lebanon. As well as the army barracks in Damascus and

the shopping area of Straight Street and a Red Cross Train at the back

of the Station burned out, the damage in other places was also substantial.

However, we restored order and the area declared

safe. Time for a Brew. As the water in the billycan T started to boil,

I bent down to switch off and drop the tea in and as I did so, a machine

gun opened up from the area of the barracks and missed my head by inches

if I had been standing, my head would have disappeared.

Back to Action Stations.

Eventually, all was declared safe. On entering

the Barracks, the first thing to attract my attention was the body of