|

Feature Page |

|

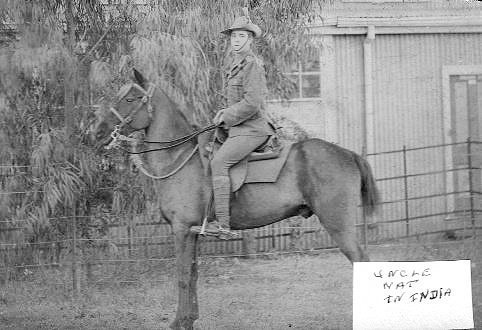

Nat was born on 14th March 1888 in Miles Platting,

Manchester. He was one of eight children born to James and Margaret

Hartley. At the age of 13, in 1901, he was living at 31 Top-oth-Green,

Chadderton, Oldham and was employed in a local Cotton Mill as a Warehouse

Boy. Tragically in May 1904, his mother died suddenly after a short

illness. Even though he was underage, Nat nevertheless enlisted into

the Army for seven years and went off around the world to try to forget

his home sadness. Nat pictured on horseback in India. |

|

When Nat returned in 1911 he went first to his sister Ada's home in Oldham. He arrived with nothing but the clothes he stood in. After a few months he travelled down to Coventry to be with his father James and brother John William in Coventry. He worked for a time at Coventry Colliery as a Bricklayers Labourer. His time in Coventry was short-lived. In 1914, WWI loomed and Nat immediately went back to Lancashire to re-enlist into his old regiment the Lancashire Fusiliers [pic shows Barracks at Bury, Lancashire]

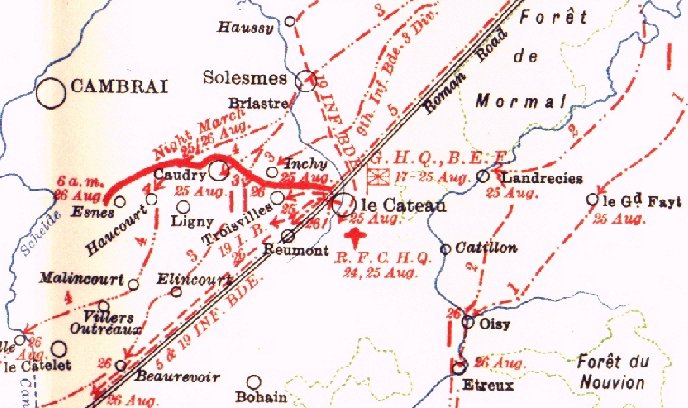

Nat in WWI The Battle of Le Cateau - Wednesday 26th August 1914

'...it is said by some that through the course of the entire war never

were British troops as heavily outnumbered'

The Campaign. South of Mons is a cluster of mining villages, then the Forest of Mormal and the vast rolling open spaces of the Cambresis. The weather was fine and warm. On the Western Front Smith-Dorrien's decision to turn II Corps around from retreat, and to stand against the German advance at Le Cateau, paid off handsomely. Serious losses were inflicted on the Germans, and another delay imposed on their Paris timetable. I Corps was able to move further away from the advance parties of the Germans. However, a serious rift grew between Sir John French and Smith-Dorrien as a result of this action. What happened? By nightfall of the 25th August 1914, the retreating II Corps was being closely pursued by the German 1st Army. I Corps was some way away to the East, and although the newly-arrived 4th Division was moving up alongside II Corps it was clear that the disorganised and greatly fatigued units faced a calamity the next day if the withdrawal was forced to continue. Corps Commander Horace Smith-Dorrien ordered II Corps to stand and fight. The units of the Corps were arranged in the open downs to the West of the small town of Le Cateau. The town of Le Cateau lies deep in the narrow valley of the river Selle, surrounded on all sides by open cultivated country, with never a fence, except in the immediate vicinity of the villages, and hardly a tree, except along the chaussées. The river, though small, is unfordable. The heights on the east, crescent shaped, slightly overlook those on the west, the highest ground of which is roughly a T in plan : the head [the Reumont ridge], running north to south, from Viesly to Reumont, and the stalk [the Le Cateau position or Caudry ridge] east to west from Le Cateau to Crévecoeur. The reverse or south side of the Caudry ridge drops sharply to the Warnelle stream, with higher undulating country behind it, dotted with villages and woods, admirably suited to cover a retirement, once the long slope from the stream up to the edge of the higher ground marked by Montigny and Ligny had been passed. The front or north side is broken by a succession of long spurs running northwards ; the western end drops to the Schelde Canal. Except for this canal with its accompanying stream, and the Selle river with its tributary the Rivierette des Essarts, the country was free for the movement of troops of all arms, and, from its open character, generally suited to defensive action, though there were numerous small valleys up which enterprising and well-trained infantry could approach unseen. Beetroot and clover covered part of the ground, but the other crops had mostly been cut and partly harvested. Here and there were lines of cattle, picketed Flemish fashion, in the forage patches. Crops had been held so sacred at British manoeuvres that there was occasionally hesitation before troops, particularly mounted troops, would move across them. The town of Le Cateau on the right of the line of the II. 4:00am: Early morning August 26: The men of II Corps were arriving in Le Cateau. They were tired, worn, and in generally low spirits. Here the word was given , they would stand and fight. They hurried to set up a skirmish line but found little cover. They were forced to deploy in the open ground, on a forward slope along the Le Cateau-Cambrai road west of town. Vulnerable and exposed the men started to dig in. To the north lay the high ground and the Germans. From here their heavy guns could pummel the British in the open ground. The men and artillery of the BEF were badly exposed. Several of the British batteries were right on the firing line with the infantry. Other batteries were only a short distance to the rear. Enemy pressure had made it impossible to dig anything other than the most rudimentary defenses. The inadequacy of these excavations would soon be apparent. Small valleys and dead ground permitted the enemy to approach without being observed. To the left of the lines civilians had dug a few trenches that were readily used by the BEF. The men of the 5th Corps held the right wing of the defense. It was their job to cover the crossroads west of the town where they were located on both sides of the Roman road leading to Reumont. To their left was the 3rd Division, and further to the left was the newly arrived 4th Division. The 4th Division had placed itself under Smith-Dorien's command for the battle. In reserve was the Cavalry Division of the 19th Infantry Brigade. Other infantry units in the area consisted of two companies of the East Surreys, Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry, 1st Queens Own Royal West Kents, 2nd King's Own Scottish Borderers, and on the road to Reumont facing to the north were the King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry. Artillery consisted of the guns of 122, 123 and 124 Batteries. To the right were the guns of 52 Battery, 37th Battery with its howitzers, 80th Battery, and 11th Battery. They were positioned in the open on the high ground at Rambourlieux Farm, 2 miles northwest of Le Cateau. 6:00 am: Gray and cloudy, a mist hung in the overcast sky as the German guns opened fire from northeast of Le Cateau. This continued off and on until around 8:00 am. Soon small-arms fire was directed at the British from west of Le Cateau. Under the cover of mist and fog the Germans tried to advance against the British right flank; they had walked into a hornet's nest. The volume of accurate British fire was devastating. Field artillery joined in and soon the Germans were forced to fall back. 10:00 am: The German guns unleashed a maelstrom of steel inflecting heavy losses to the besieged British forces. The men of The King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry, and the Suffolks who held the front line were literally pulverized by high explosives and shrapnel. Now the Imperial German Army began their attack. Like a great gray sea the Germans advanced on a 2-mile front from the valley of the Selle to Rambourlieux Farm. These huge formations proved deadly for the Germans. What followed can only be described as a massacre. The rifles and field guns of the BEF took the lives of many brave Germans. The toll was also great on the British. The unceasing artillery, machine gun, and rifle fire flailed the men of the BEF. Only one gun of 11 Battery was now operational. The guns of the remaining Batteries rained death on the advancing Germans. The guns 122 Batteries wiped out a whole platoon of Germans. The others broke for cover. 12:00 Noon: Machine gun fire and rifle fire was battering

the Suffolks, and the final gun of 11 Battery was now out of action.

Hastily the men of the 2nd Manchesters, the Argylls, and Sutherland

Highlanders were ordered up to help the beleaguered Suffolks but they

were strafed by enemy fire and suffered severe losses. Steadily the

German attack continued. Towards the left flank the Germans mounted

an attack but were repelled by the rifle fire of the BEF. Again the

valiant Germans rallied and charged. Under a hail of bullets, some determined

forces made it across the Cambrai Road but were chopped down by the

machine gun of the Royal Scots near Audencourt. To the far left the

British were under heavy attack from artillery and machine gun fire.

The King's Own Royal Lancasters had 400 casualties. The Lancashire Fusiliers were being hit hard by

some of the 21 machine guns the Germans had in that sector.

1:00 pm: The situation was now critical. The guns of 122, 123, and 124 Batteries were in jeopardy. A call went out for volunteers to retrieve the guns. Captain R.A. Jones of 122 Battery gathered his men and six fearless teams of horses and was ready to attempt the task. Jones inspired his men by leading them down the battered hillside towards the guns. German machine gun fire tore through the teams. Eight men, including Captain Jones, and twenty brave steeds fell. The other teams reached the guns and limbered up three of them. One team was shot down in the road. The other two galloped up the hill past the men of the West Kents. They waved their hats and cheered wildly as they galloped by. "It was a very fine site", stated one British officer. Acts of courage filled the battlefield but none were more daring than the story of Captain Reynolds of the 37th Battery. With a hand full of volunteers they charged forward to rescue two howitzers that had been left in the open. With the Germans only 200 yards away the men limbered up the guns. They galloped away but one team fell to artillery fire. The other team of Reynolds and drivers Luke and Drain made it back. For their bravery in the face of death they received the Victoria Cross. 2:00 pm: It was now evident that the British could not hold out much longer. Plans were being made for a general retreat. The guns of 123 and 124 Batteries could not be saved. The sights were smashed and the breeblock removed making them, worthless to the advancing Germans. All across the lines, the BEF was being over run. The men of Suffolks and Elements of the 2nd Manchesters, the Argyll, and Sutherland Highlanders were under heavy attack and were suffering severe losses. 2.30 pm: The end was near. The Germans had the Suffolks' on the ropes. They countered, fighting back fiercely. In company with the Argylls, they fought like warriors from the days of old. Scotsmen made a final stand next to Englishmen. All ancient feuds were put aside. Two of the Highland officers started counting aloud each one of their kills; alas, it was no use. They had taken artillery fire throughout the battle. Now the determined Germans rushed their position and, after fierce fighting, the Suffolks and Argylls were finally silenced. The Germans now turned their attention to the men of the King's Owen Yorkshire Light Infantry. All across the battlefield the order was being given to fall back but they had not received this message. From the right rear and from the Cambrai Road, the Germans attacked with rapid rifle and machine gun fire. The Yorkshire men took a pounding but held on. Finally, the Germans rushed their position and they were overwhelmed. Their last stand made it possible for the 5th Division to start its retreat. Some members of the 3rd Division's West Kents and the Scottish Borderers were captured because they never received the order to fall back. 4:40 pm: French Cavalry had finally arrived. They set up a line to the left rear of the British forces. Their rapid-fire artillery began to pound the Germans' flank. This diversion allowed 4th Division to slip away. To the north and east, many British Divisions had not received the order to retire, and fought on. The BEF was now in full retreat. General Smith-Dorrien had already moved his HQ to St. Quentin. Late afternoon 26 August: Darkness was falling on the battlefield, and with it came a drizzling rain. Isolated pockets of the BEF held out, forming a rear guard. These selfless deeds allowed the remaining forces to escape. Except for long-range artillery that did little damage, the BEF retreat was uncontested. Tactical victory belonged the Germans; moral victory to the BEF. II Corps had not been overwhelmed, nor had they been destroyed. Loses were high for the British - Casualties The total British casualties amounted to 7,812 of all ranks, killed, wounded and missing. 38 guns were lost. German forces had suffered even heavier losses. The

uncontested retreat of the BEF gave the Allies breathing space and time

to regroup. Smith-Dorrien had disobeyed Sir Johns' order to retreat

and Sir John never forgave him. Yet his brave decision, although costly,

had saved the war for the Allies. On the German side, it became evident

they could not afford another victory like the one at Le Cateau.

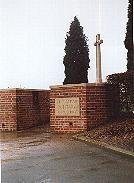

Cemetery: Grave Reference: I at Esnes Communal Cemetery,

Nord, France. Esnes is a village in the Department of the Nord, 8 kilometres

south-east of Cambrai. The Cemetery is north-east of the village on

the road to Langsart. The British cross of sacrifice can be seen in

front of the poplars, behind the pyramid of a German unit memorial.

Esnes witnessed fighting in the Battle of Le Cateau

[Wednesday 26th August 1914] and it was eventually captured by the New

Zealand Division on the 8th October 1918. In the corner of the Communal

Cemetery, are five graves; one [marked also by a French memorial] contains

the bodies of soldiers of the 4th Division who fell in August, 1914,

and in the others are buried soldiers who died later in the War. There

are now over 100, 1914-18 war casualties commemorated in this site.

Of these, over half are unidentified and a special memorial records

the name of a soldier who fell in the Battle of Le Cateau and is buried

in the cemetery, but whose grave cannot now be traced. The British graves

cover an area of 214 square metres.

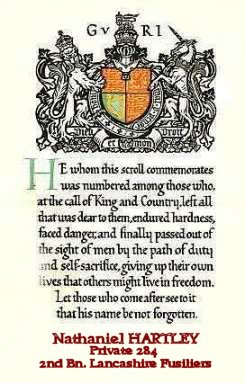

WWI Memorial Scroll and Plaque It was decided during World War One that all next of kin of service personnel who lost their lives as a result of the war would be presented with a memorial plaque and commemorative scroll from the King and country. I believe [but I am not certain] that none of the commemorative plaques and scrolls were delivered to the bereaved families until the early 1920's. The designer of the plaque was Mr. E. Carter Preston of Liverpool England. The manufacture of these plaques was under the direction of Mr. Manning Pike at the Memorial Plaque Factory in London. There were difficulties in the manufacture with due to the casting process as each plaque had the late serviceman's or woman's name individually applied. Sadly the scheme ended before all the bereaved families received their plaques and scroll. The plaques were cast in bronze and were approximately five inches [250 mm] in diameter. The photograph of one of these plaques which would have been sent to the next of kin of a John Mills, also a copy of a [blank] "honour scroll". On the plaque itself no rank was given as the intention was to show equality in their sacrifice. In Memory of Private Nathaniel HARTLEY 284, 2nd Bn., Lancashire Fusiliers at approximately noon Remembered with honour

|