this book was written in 2004

This book is for my granddad I'm proud of

him you see

He's been through war "n" things you know

It wasn't the place to be.

He's been to every country

Met every person too

Remembered all their names as well

Now that, I cannot do.

A photographic memory

That is what they say

So he put it down on paper

A bit he did each day.

It took him quite a while

So much of it to do

So granddad what I've done with it

Is made a book for you

With love from your very proud granddaughter

Kay x x

The True Life Story

of Herbert Ormerod

This is the true life story of Herbert Ormerod, that's me. I was born

on the 13th March 1915, at number 6 Chapel Street in Stacksteads. I later

found out that I was called Herbert by my mother who said that when my

brother Jim came home on leave from France she asked him what I was to

be called. He said, "Why not call him Herbert after my mate Herbert

Fleet who was killed at the same time as I was wounded at Hooge in Belgium?"

Well the time came when I had to attend school which was the Tunstead

C of E. The first day my sisters took me I ran back home. This went on

for months, then, after a bit, I settled down, but I didn't like it one

bit. That's why I can't spell today. Well when I was about ten and school

had finished for the day, I went up to help on a farm up on Tunstead Top

called the Folly Farm, which was owned by the farmer called Edgar Disley.

He was a nice bloke and after I'd finished my jobs on the farm he used

to let me stay in the house for a pot of tea and a bit of homemade apple

pie. My job was mucking out the shippons, the stable and the pig-sty,

and sometimes the hen cabins. It was one day after I had finished cleaning

the cabins that I found hundreds of hen fleas crawling all over me. On

seeing them, I ran like the devil home and when my mother saw me in that

dirty state and scratching, she said, "Don't you come in here. I

don't want fleas in the house!" Then she made me strip all my clothes

off in the middle of the street with everybody watching and having a good

laugh at my predicament. Well in a bit she came out with a tin bath, and

then started filling it and putting in some disinfectant of some sort.

Then after she'd finished scrubbing me, she made me get out and get dried

and told me to go inside and put some clean clothes on. After that I felt

grand. Then my mother burnt my clothes and told me never to clean out

hen cabins again or she would kill me. Well I didn't, and I never have

done to this day.

Then the time came to start mowing for haymaking, so one Saturday after

we'd finished delivering the milk, Edgar turned the horse out to graze

in the field, then went in the house for his dinner. I went home for mine,

because it wasn't so far and after about an hour and a half, I went back

to the farm and called at the house. He said, "I think we'll start

mowing this afternoon. It's a grand day for it." So I said okay and

told him that I was going to bring the horse and hook it into the mowing

machine. He said, "Mind what you're doing. She can be a devil sometimes."

Anyway I went and found that she'd gone to the far end of the field and

was standing in a corner. I was about to get hold of her halter when she

swung round and lashed out with her hind legs and kicked me in the arm,

breaking it, and knocking me down. I must have been laid there for a good

half hour before Edgar came and found me and asked what had happened.

I told him and he said I'd better make my way down to the farmhouse and

wait there until he came with the horse. Well I set off with Edgar following

behind with the horse, and when I met his wife she was very upset when

she found out what had happened. She said she would take me home and when

we arrived my sister Edith took me to Doctor Shaw in Bacup who set my

arm and put it in a sling. Then Edith and I came back home and my mother

said, "You'll get killed one of these days, messing about with horses.

Just watch what you're doing. Anyway you'll still have to go to school."

After five weeks in plaster the doctor took it off and said it was better,

but would feel stiff for a week or two, then it would be normal.

One thing that happened that year was the coalminers' strike, which made

all the cotton mills close because they depended on coal to fire the boilers.

It was the same for the railways. Then the shoe and slipper industry stopped

and that meant a general strike all through the country. At home and at

other homes in the valley people were getting desperate to keep the fires

going, mainly for heating the water for washing clothes and bedding.

So what we did was to go and get our own coal. There was my brother, me

and a few more went up to a few slag heaps on Tunstead Tops, where the

Isle colliery was, but not working. We used to take buckets, tin baths

and old hessian sacks to bring back the coal in. I remember one day, about

five of us went to a place near the Slip-In farm, where there were some

old mine workings. It was here where an old collier called Sam Collinge

started digging and broke through into a tunnel that led into the old

mine workings. He must have gone in a good hundred yards, and then the

roof came down and buried him. I ran over to the farm for help and when

the farmer heard me shouting my head off that Sam Collinge was trapped

in a tunnel, he went into the barn with another bloke. They brought some

picks and shovels and started digging. Whilst this was going on another

lad went running down to the Top-Of-The-Bank-Farm and to Mitchell Field

Nook Farm for help, and after a bit a doctor and an ambulance called at

Mitchell Field Nook and picked up two men with some timber and a few fence

posts and shovels.

They managed to get to within about 400 yards of Sam but then had to stop

because of the bad terrain. After a lot of hard digging and putting up

roof supports, they found him badly crushed, and when the doctor examined

him he said he was dead. So after a struggle he was brought out and placed

onto a stretcher and carried down to the ambulance. But still after this

tragedy, people kept going up there to dig for coal. This went on for

months, even after the strike was settled.

I then went helping on another farm called Middle Tunstead, which was

owned by Jim Pickup, who used to deliver coal with a black horse that

used to bite. He also had three daughters called Annie, Mary and Jenny,

then a son called George. I liked working here, mostly with the cattle

and the donkey. The best part was when George and I went delivering the

night's milk with the donkey. We used to start delivering at Rook Hill,

over Booth Road to Church Street. Then George would leave me to go courting,

so I would deliver in Church Street, Union Street, Plantation Street and

finish in Dale Street in Stacksteads, and then back to the farm to unharness

the donkey and give it fodder and water if it was winter time. But in

good fine weather, I would put it out to graze in the little field near

the farm house. Then I took the milk tins in for washing, and George's

mother would give me a nice drink of tea and a piece of her home-made

cake. Later, I would leave for home. Sometimes I would call at the chip

shop at the bottom of Church Street and get a bag of chips and eat them

on my way. I did this every night until I left school at 14. That was

in 1929.

After a week I got work at Olive Mill in Bacup, which was a shoe and slipper

factory. My first job was pricking and marking in the clicking room, then

cutting shoe linings on a board, then after a while I went on a press,

cutting leather uppers. After working here for a few years the firm went

on short time working, which meant the dole for the most of us. Well that

wasn't for me so I decided to go into the building trade because just

then there were a lot of houses being built all over.

I managed to get a job up at Newchurch at Waterfoot, as a labourer to

a bricklayer called George Heap. It was there that a young boy was playing

over a lime pit, trying to push a wheel-barrow on a plank when he fell

into the pit. Luckily two workmen saw him and pulled him out, then got

a water hose and sprayed him with water. The lad looked to be in a bad

way. He said his eyes were burning and he couldn't see. An ambulance came

and took him to the hospital for treatment. His dad, Jack Nicholson went

with him. Later on in the afternoon they came back and his dad said his

son was better, but he wasn't to play anywhere near the houses again.

There was another bad accident a few days after. One of the joiners who

was putting windows in tripped over a piece of timber and fell as he was

carrying a pane of glass. He nearly severed all his fingers and he was

taken in a car to the Rossendale General Hospital to get treatment.

When the houses were finished I got another job, this time working in

Haslingden for a firm called Drakes Builders. They were building a chimney

and a big lodge for holding water and a filtering plant. After that I

worked up at Crawshawbooth widening the road and covering in the river

by placing steel girders and concreting in between them. Then I worked

on widening the bridge in front of the Sunnyside Printworks and during

the dinner break we used to go into the Printers Arms nearby.

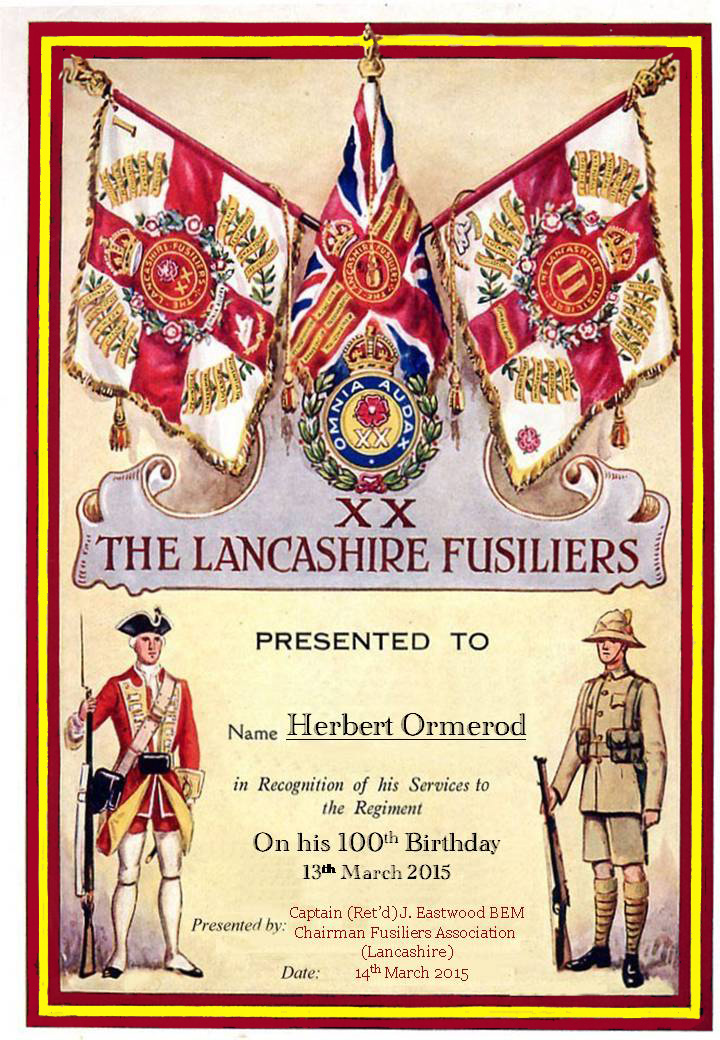

Well it was round about this time in January 1938 that I joined the 6th

Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers, a Territorial Army Unit.

My girlfriend, Alice Howarth,

who I had courted for five years and who lived in Bacup, played holy hell

when she knew I'd joined the army, because she'd been reading the daily

newspapers that told of things that were happening in Germany. I told

her that it was best to be prepared; there were a lot of lads joining

up.

We finished the work in Crawshawbooth and then I went working for the

Bacup Water Works, laying pipes up Cutler Lane in Stacksteads, then up

Thorn Estate in Bacup. It was whilst I was working in Bacup that Alice

and I decided to get married, and on Saturday the 16th of July 1938 we

were married at Saint Saviour's church up New Lane in Bacup. It was a

lovely day for everybody. Alice looked smashing in her dress and also

the bridesmaids. As we came out of church the girl guides formed a guard

of honour, which we thought was very nice. Then, after the church ceremony,

we all went to the Bacup Co-op Cafe for the reception which I think everybody

enjoyed as well. After the cake was cut and the speeches had been made,

my wife and I went to see a variety show in Burnley.

We both enjoyed it very much, and afterwards went back to our new home

which was just a back to back dwelling, but to us it was a palace. We

didn't have a honeymoon until a few years later because money was scarce,

and also because of our other commitments. The month before the wedding,

all Territorial units had been sent for special training. Our Battalion

went to the Gower Peninsular near Swansea in South Wales for a fortnight,

and then it was back to laying pipes in Bacup.

photo

This pipe laying went on for two years, first of all starting up Cutler

Lane in Stacksteads where Henry Tricket the builders had started to build

about eighty houses -it's now called Greens Estate. We were laying a new

water main from the Bacup Road all the way to the top of Cutler Lane,

and then other pipes branching off to the avenues that went round the

houses. Sometimes we helped the plumbers to fix the smaller lead pipes

inside the houses, and I sometimes had to go out with a lorry driver to

bring plumbing materials to the different jobs and that made a nice change.

After working up Cutler Greens we then went up onto the Thorn Estate in

Bacup, doing the same thing. These houses were built by Thomas Coats of

Bacup, who was well known by most of the people of Bacup as Ready Money

Tommy. Then when that job was finished, we went up Burnley Road in Bacup

to Broadclough Mill to lay a water main and to put some new water valves

in.Well, reading the national newspapers, things were looking a bit grim

and everybody was talking about Germany and the things that were happening

there. Also all the local councils were asking if they could go round

to people's houses and inspect their basements or cellars, to see if they

were suitable for an air-raid shelter. There was a lot of activity making

blackout material too, and making sandbags.

It wasn't long before a bloke at work called Jim Eagan, said that his

brother John had to report to Fulwood Barracks and rejoin his Battalion

which was the North Lancashire Regiment, or the Loyals. So I said, "It

looks like the rest of the army is being called up." Anyway that

night it was there on the table. A brown envelope with HMS on the front.

"Well," I said to Alice, "it looks like war as all the

naval and army reserves are being called up to report to their units."

That was at five o'clock at night, so after tea I made my way to the drill

hall in Rochdale and reported to the Regimental Sergeant Major, who told

us all to go to the quarter master and get issued with our kit. Then those

who lived up to ten miles away were told we could go home and report back

there in the morning. Well, that wasn't so bad. It gave me a chance to

sort things out at home and at work. The boss said it was expected, so

not to worry. He told me that my wife would still get my wages for the

first three months, and after that it would be reduced to half, then it

would cease after the next three months.

So that was my entry into the war. Please read my other writings about

my army life. I hope you like it, and some of you will remember the times

when Manchester and Salford got blitzed, and all the rejoicings afterwards.

War Memoirs Of A Bacup Lad

There had been an air of expectancy that something was going to happen,

despite the declaration of peace in our time.

"3449863 Fusilier Ormerod H, to report to the Drill Hall Rochdale

at 1700 Hours 28/8/39." This was it.

The issuing of equipment, including a Rifle, made things look grim indeed,

and having been kitted out we were sent to guard a Royal Airforce Factory

at Heywood. On Sunday the 3rd September I was on guard duty when my Officer

came along and told us to stand down, and that war had been declared with

Germany. Later that day my wife came to see me. We were given permission

to go home for the day. On reporting back to Battalion we were put on

full alert and put on special training, and afterwards we were moved to

Barrow near Whalley. The memory I have of this time is of the very severe

weather conditions. I can recall our unit and a company of the East Lancs

being sent with shovels to try and dig out a train which had been trapped

in a snow drift and stuck for four days near Hellifield.

Alice my wife was at this time rushed to hospital in Bury. My commanding

officer gave me a pass so that I could go home to Bacup and visit my wife.

There were four other lads from Bacup who had also got passes, so we decided

to travel together. Our journey started fine in a Bren Gun Carrier, but

after we'd been travelling for about a mile it happened. Yes we were stuck!

Out we got and there was nothing we could do except to walk it if we were

to get home. After ten hours slog we arrived at Bacup wet through and

dead on our feet. The following day I went to the hospital where Alice

was a patient. Unfortunately though, she was in an isolation ward and

we only managed to see one another through the window. It was poor consolation

after my trudge through the deep snow, but my father was able to go and

see her most days and he kept sending me reports on her condition which

cheered me up no end.

I reported back to my unit in time to move camp to Ripon where we joined

the 9th King's Own Royal Regiment and a company of the Scots from the

Gordons and Seaforth Highlanders, for intensive training with grenades,

machine guns, rifles and bayonets. After we had passed out we were allowed

leave for 48 hours, but whilst I was away, the unit, at a moment's notice,

moved south, and when I got back to Ripon I found the Royal Welsh Fusiliers

instead of my own unit there. I was put up for the night in a hut full

of Taffies all speaking Welsh, and I was glad when, the following morning,

I was issued with haversack rations and a travel warrant to catch up with

my own unit in the south. The journey, including three changes, was very

tiring and seemed to take forever, but at last I rejoined my unit at Godstone

in Surrey. Our billet was a large barn, or what was left of it - no doors

and half the roof missing! We were camped here for a fortnight, then to

our relief things began to happen. We were issued with rations and ammunition

and marched to the railway station about a mile away to board a train

for Southampton, where we then boarded a troopship for France.

But just before we started to go up the ship's gangway, I met a soldier

called Jack Haworth, whose parents kept a chip shop in Bacup. He wished

me good luck and a safe journey and said he hoped we would meet again

in happier circumstances.

The troop ship was a small transport, which used to sail between Liverpool

and Belfast and also to the Isle of Man. After a trouble free crossing,

we arrived at the French port of Le Havre, and after disembarking we had

to help to unload another ship. Then we marched to the station and boarded

cattle trucks to a small town called Fauville, but we didn't go into the

station, we had to walk a mile, after which our company left the rest

of the battalion and we carried on for another mile and at last arrived

at a farm. Each platoon was shown to their billet and ours was in a big

dutch barn. To get in you had to climb a ladder. Well, each one of us

was given orders of some kind. The first thing was getting a meal, which

was corned beef stew and some nice French bread and a pot of tea. Then

a guard was mounted and the company officer came round and told us to

keep out of trouble. Also he warned us to be careful whilst staying in

the barn. If we wanted to smoke, we had to go outside.

We hadn't been there long when the heavens opened and we all made a dash

for the barn. We got settled down for the night, but it couldn't have

been more than ten minutes when there was a bloke shouting,

"Get up! There's rats all over the bloody place!" Then somebody

struck a match and lit a lamp. You could see the blighters running along

the ledges and feel them under the hay. Most of it was horse bedding by

the smell of it, so me and a lot more of the lads got out and spent the

night sleeping under the trucks. Although it was raining hard, it was

better than being eaten by the rats.

I was glad when it came daylight and a call came from the farmhouse. Me

and two of my mates went over and who should it be but the farmer's wife,

holding a large jug full of hot coffee and milk and two boiled eggs each.

I think she charged us six francs for the lot. After we had cleaned ourselves

up, we went down into the town and had a good look round. It was a lovely

place, with nice gardens and shops and a couple of cafes where English

was spoken.

About ten days later the battalion got orders to move again, so it was

back on the cattle trucks to the station and we travelled to a big mining

town called Lens. Just going into Lens we went past some sandbagged dugouts

from the First World War. They had, in big letters, the names of regiments

who had served in them. Half a mile further on the train stopped and we

all detrained to get a wash and some grub, which was the same bully beef

stew and tea.

To get a wash we lined up at the end of a railway shed and the water barrel

we washed in had about an inch of scum on the top. Well, I thought, I'm

not washing in that muck. So I went looking for a bucket or something.

Anyway, after a lot of scrounging I managed to find an old biscuit tin

and went up to the engine driver for some hot water. He motioned me to

hold the tin under a steam pipe until it filled up and it was grand to

get a good wash and shave in hot water - the first wash we'd had for two

days.

After that brief stop, the train pulled out of Lens and took us to another

mining town called Vermelles, ten miles away. Here the Battalion HQ Company

was billeted and the four rifle companies were in the small mining village

of Bully-les-Mines, where a lot of fierce fighting took place during the

First World War. Our platoon's quarters were in some derelict houses,

and others were in an old granary swarming with mice. There was also a

massive war cemetery where thousands of British soldiers, French and Germans

were buried. There were a lot of Lancashire and Yorkshire lads amongst

them, some of them only nineteen years old.

One day all the company had to parade with their towels, and be marched

to a big colliery on the Béthune Road. The colliery was called

Philosophy and we arrived sweating. Then we all filed into the pit baths

and each one, after undressing, had to wind their clothes up to the ceiling,

then go under the showers. The best thing was when the women came round

giving you soap, which was a brown colour, they didn't seem to mind seeing

us in the raw. I think they liked it. As they were going away the lads

were giving them wolf whistles. Well, after we all had our baths, we formed

up again into three ranks in the colliery yard, but just then an overhead

waste bucket started tipping colliery waste, which blew all over the place,

making us look like minstrels as it stuck to the sweat.

We marched back into Bully-les-Mines and started preparing to move once

again. This time to Lille, ten miles from the Belgian border. My company

was billeted in the next town, called Tourcoing and the others in Roubaix.

Here we went out to dig trenches and deep dug -outs in all the three towns,

most of them in parks and near to main cross roads, but also in places

road blocks were set up and manned by us. Meanwhile more troops were moving

up near to the Belgian border, all home leave was cancelled and we were

confined to our billets until further orders. But before these orders

were given, me and my mate went up into Lille for a stroll and to see

what the place looked like. We went into a couple of cafes, then decided

to go to see the town of Armentières. We hadn't long to wait for

a tram. We arrived and had a good look at the place, but the time was

getting late so we set off back as we thought, but the tram went another

way and the conductor said that was as far as we could go, so we had to

get off. We walked for a good half hour until we came to some crossroads,

where two Belgian gendarmes wanted to see our papers. They asked us the

name of our unit and when we refused to tell them, they took us into a

police post and took possession of our pay books. They kept us for at

least two hours, then a British Army Truck came and picked us up and took

us back to our company. When we got back we had to report to the orderly

officer and explain where we had been when the Battalion was on orders

to move. Well we told him the truth, and after a good dressing down he

told us to get our kit ready, and after waiting about eight hours we eventually

moved out in company order and joined the rest of the Battalion just outside

Lille. The time was just six o' clock in the morning of the 10th May 1940.

We moved in convoy with a lot more of the 42nd East Lancashire Division

and came to a town called Tournai, which was in the middle of a bombing

raid. The houses were on fire and the railway station was partly demolished.

I saw a large steam locomotive that had been lifted and flung onto the

platform with the bomb blast. Luckily we all got through and carried on

into Belgium. On and on we went, going through a lot of flat country and

small villages until, after going through the village of Lessins, we pulled

off the road and went up a farm track where we got down from the trucks.

Each platoon was told to dig in and try to get some rest. Our trenches

were right near to the farm house, and just as we had finished digging

we heard a lot of gunfire coming over from our rear. Our officer said

they were our guns that were firing on German positions, and not long

after German guns started to retaliate and we could hear the shells going

over, bursting a mile back.

Our cooks made some effort to make us a meal and the farmer came out of

the house bringing some hot coffee and home made bread and hard boiled

eggs. After we had eaten, the guards were posted and the rest of us settled

down for the night. It must have been about two o'clock in the morning

when a lot of gunfire was heard up towards Brussels and over to our left.

Shells were going over us and bursting about two miles away. Then the

farmer came out with his wife, carrying bits of furniture and bedding

and anything they could carry. He came and asked us if we would help him

to load the cart and bring the cow from the field and tie it to the back

of the cart. Well we all mucked in and they said they were heading south

towards the Somme. It was terrible to see the old farmer and his wife

having to leave their home and all the cattle and the fields of corn and

everything they owned.

When morning came, we were off again, going towards Beauregard, when we

halted because of a big traffic hold up. The road ahead was littered with

smashed vehicles of all kinds by a bombing raid and a lot of refugees

had caught it. Some were badly wounded and one or two killed. Then it

was our turn to be hit by Jerry, but not by bombing. This time it was

by low flying fighters, machine-gunning everything on the road. I saw

a cart load of women and children being shot up, also their horse had

been shot and was lying in the road thrashing about, trying its best to

get up onto its feet.

Later on when the road was cleared we were just about to move off when

a car pulled up with two adults and a young girl in. The driver must have

overheard some of the lads talking in broad Lancashire. He asked our officer

if he could find him some petrol, just to get them to the coast. He said

they'd had to leave Brussels in a hurry and that the petrol tank was showing

empty. He said he was the under manager at the Courtaulds factory in Brussels

and his real home was in Tottington near Bury. The officer gave him two

tins and filled the tank and also gave him about fifty woodbine cigarettes

and wished them a safe and comfortable journey.

Well, after that little incident, we started to move forward to a place

called Ninove, about fifteen miles from Brussels. It wasn't long before

we were again under enemy attack from the air. We were bombed and machine-gunned,

but the only casualties were about eight soldiers of the Middlesex Regiment

and a few civilian refugees. All the troops in the column opened up with

small arms fire, from Bren guns and rifles. Later we came across a lot

of smashed trucks and horse drawn carts and hundreds of people fleeing

from the Germans. Just before entering Ninove, our platoon took up positions

at some crossroads. Six of us broke through a wall in a corner house to

fix up a machine-gun and whilst we were doing this a woman came into the

room and started to pack clothing and other things into suitcases and

bedding into a pram. She told us that she was leaving and that we could

stay and have as much food as we wanted. She said her husband was in the

army fighting in and around Liège. Well we thanked her and hoped

that she and her young daughter had a safe journey, and that her husband

was safe and would come through the fighting okay. Then we watched them

go, with the pram piled high with their belongings and tears streaming

down their faces. It was a pitiful sight to see them having to leave their

home and their most treasured possessions. I've often wondered, and still

do, if they ever came through and got to safety.

We fixed up our Bren light machine-gun and waited for the enemy to appear.

Some more of our company were in positions at the other side of the cross

road giving cross fire with their machine gun. There were also some of

our three inch mortars positioned in vegetable allotments. We didn't have

to wait long before we came under enemy shelling. Most of the shells went

well over us and burst on the Royal Ulster Rifles positions, but then

Jerry started dropping his shells short with some landing just in front

of us. Part of the house we were in got a direct hit, blowing in part

of the gable end and part of the roof. We were very lucky not to have

been killed or injured. The only thing was the plaster and parts of the

roof coming down on us.

Soon the shelling stopped and in the distance we could see the German

infantry moving down a street about five hundred yards distant. Then they

came under intense small arms fire from one of our companies. I think

it was B Company. Then it was our turn to open fire. There must have been

at least two hundred of them who tried to get over the crossroads. We

let them come on to about one hundred yards than let them have it. You

couldn't miss. They were shot to pieces. I think out of two hundred, only

about twenty made it across and they were taken prisoner.

We stood fast to our positions. Then Jerry made another attack, this time

with tanks. They broke through on our right, causing us to fall back under

brigade orders. We waited until dark then moved further back into some

corn fields on the right of Ninove. Here we dug trenches alongside another

infantry unit called the Middlesex Regiment. We saw a lot of wounded riding

on all kinds of vehicles and most of the soldiers were from the Guards

regiments, who were fighting along the canal banks east of Louvain and

Brussels. We could hear tremendous explosions all along our front where

the Royal Engineers were blowing up bridges that the Belgians had failed

to destroy. But it was too late to stop most of the German heavy stuff,

such as guns and tanks from crossing. That was the trouble. We hadn't

anything big enough to stop his advance. He also had dive bombers to bomb

at will.

Well we dug away like mad and were expecting the enemy to put in another

attack when a dispatch rider came to our position and handed the officer

some letters and dispatches and a parcel for me. The orderly sergeant

came down the trench to me and said,

"You lucky sod Ormerod!" The lads came round and had a good

look and when it was opened their eyes bulged out when they saw the cake

and other things. The cake was a bit squashed, but was lovely after not

having anything to eat for twelve hours. About ten of us had it and the

officer said it was the best he'd ever had. We said our thanks to those

at home for all the other things too, which were socks, scarf, sweets

and cigarettes, and a nice letter wishing me and the rest of the battalion

good luck.

Not long after we came under more shelling and heavy mortar fire. It caused

a few casualties but not serious, just shrapnel wounds. The order was

then given to pull out and withdraw to new positions and dig in again.

We set off towards a town called Oudenaarde. About a quarter of a mile

from the town an officer from the Royal Engineers told us to hurry, because

they were going to blow the bridge. Everyone started to run although we

were very tired, and we'd only just crossed when it went up with a hell

of a bang causing everybody to scatter and duck. There were things flying

everywhere! This bridge was the main bridge over the River Schelde into

the town.

The troops lining the river banks were a machine gun battalion of the

Manchester regiment and a battalion of the Lincolnshire regiment. We were

then ordered to dig trenches about a mile further back in case they had

to pull back. As we were moving through the town there was a big air raid.

German Stukas came over, dive bombing the town, hitting a large church

where a lot of refugees were sheltering and tending to their wounds. When

we looked again the church was blazing so our officer detailed a dozen

blokes to go with a sergeant and try to help the refugees. Some had been

killed outright and some badly wounded.

After about an hour the lads came back to join the company and later we

halted to dig in. A German fighter plane came over as we were digging

and started to machine gun us, killing our sergeant and wounding seven

privates of another platoon. Then the enemy started shelling us again,

hitting some of our trucks and setting three on fire. Then, on our immediate

left, a battalion of the Royal West Kent regiment put in a fierce attack

on the enemy positions where the mortar fire was coming from. Trying to

avoid being captured, the Germans came in front of our positions, right

into our gun sights. So we opened fire with everything. First the mortars,

then with rifles and machine-guns. The Germans lost many, killed and wounded,

though we lost none. But later the enemy brought up tanks, something we

all dreaded, because we hadn't anything to stop them - only the artillery

two miles to our rear, who gave us good support as we were ordered to

withdraw and to take up new positions further back.

On our way we came across some of our troops who had been wounded and

couldn't go any further. They hadn't any transport so what we had left

we gave to them. That left us a few short. The ones we kept were for the

rations, ammunition, anti-tank rifles, big packs and medical supplies,

as well as a water tanker. We carried on until we arrived at a town called

Kortrijk. There we dug more trenches and afterwards the cooks managed

to make us a warm meal of bully beef stew and some bread they had managed

to get from a bakery. There was also some tea and it was the first warm

meal we had had in three days.

Then we moved on again to a town called Mouscron. Here we had to make

a big road block under a railway bridge and take up positions on the railway

embankment. Again we were bombed and machine-gunned from the air. We could

see some of the houses nearby were on fire and others were completely

demolished. You couldn't see anything for smoke.

Some of us were ordered to bring anything heavy to make a road block.

In one house we went into we found an old woman in bed. She was a cripple

and was unable to move. We set about trying to get the bed through the

door, but it wasn't possible, so we had to smash a window and break the

frame and part of the wall to get the bed out. Then one of our drivers

took her to a large building where some medical staff could look after

her. We also came across some houses where the occupants kept pets, such

as rabbits, cats and dogs and also canaries. We released them to the wild,

though not the rabbits. These were killed for eating. The cooks, with

a few defaulters, skinned them and made us rabbit stew. It was a nice

change from bully beef and biscuits.

Not long after, the enemy started to shell us and their infantry put in

an attack on the railway station where the West Yorkshire regiment were

in position. Then they came down and over the banking trying to cut the

West Yorks off. That's where we went into action. We let them come nearly

to the bridge, then all hell broke loose as we fired all our mortars until

their ammunition ran out. Then our artillery opened up. At that the enemy

were stopped in their tracks and started to fall back. All our brigade

then started to go forward and pushed Jerry back for over a mile before

digging in again, expecting the enemy to counter attack.

After this action we were again ordered to fall back, this time going

through places where there had been fierce fighting in the 1914-1918 war

- such places as Halluin, Menen, Ypres and Kemmel. At Kemmel we stopped

at a big wood and dug in some old First World War trenches. We dug up

all sorts of soldiers' equipment - broken rifles, old webbing, steel helmets

and some old rifle ammunition which had gone rusty. Whilst we were digging,

I spotted someone crawling through a ditch. I told my mate what I'd seen

so he said,

"You try and get round behind him whilst I keep him covered."

Well that's what I did. I came at him from behind. He didn't hear me coming,

and when he saw me he burst into tears he was so glad that I was British

and not a German. He had been wounded in both legs and was in a bad way.

I called out to my mate and between us we got him into the trench, then

shouted for someone to bring a stretcher and the M.O. After about five

minutes the lad was seen to by the M.O. and the company officer, who asked

him which unit he was from and where it was in action when he got wounded.

He told them his regiment was the Fifth Battalion the Royal Scots, and

was cut off about a quarter of a mile away. After they had taken him away

Sergeant Gale, our platoon sergeant, took me and two more up onto a hill

and into a small wood to see if we could spot the German positions. We

sat up there for a good half hour but the only thing we saw was a few

gun flashes in the distance.

We came back to our trenches and reported to the officer. Not long after,

a German spotter plane came over, circling our position, but before this

happened a farmer, as we thought, had come round selling hard boiled eggs

and was later seen in a ditch with a radio, transmitting our position

to the enemy. All hell broke loose as enemy bombers came diving down,

dropping bombs and setting fire to the wood and blowing up three of our

trucks. Then Jerry fighter planes followed and started machine-gunning

us. There was nothing we could do only drop flat and take cover. I dived

under a truck and thought, well, this is it! There were bomb fragments

flying all over the place. One piece went right through my pack and mess

tin, and another cut the heel off my left boot. When it was all over,

I looked around and saw that the truck I'd been sheltering under was riddled

by bullets and bomb fragments. It was very frightening. I would sooner

be shelled than bombed any time.

Later on our officer came with the sergeant major to see if we were all

okay. About ten of the lads had been hit but only one, a lance corporal,

was in a bad way. He was called Frank Brennon and came from Liverpool.

The M.O. did what he could for him, but unfortunately he died during the

night; when it broke daylight we buried him near to the road and put a

cross over the grave with his name, rank and number, his age and also

his regiment.

Later that day we were ordered to move again. The first thing I did was

to find the quartermaster and get a fresh pair of boots and also a pack

and a mess tin. Well he found me the things I wanted, but the boots hurt

me after walking a mile and were causing blisters and rubbing the skin

off my heels, so I sat down and said bugger this for a lark and hoped

a truck would come along to give me a lift. Soon M.O. came and saw me

sitting at the roadside and asked me how I was. I told him what had happened,

so he made me take my boots off and then he just put plasters on and said,

"Just stick it out until we stop at the next place and if they get

worse I'll try to get you on a truck with the wounded." I carried

on walking in agony for another three miles, then a lot more of the lads

fell out of the column and a three ton truck stopped and picked us up

with some of the wounded who had to lie on some army packs and ammunition

boxes. We hadn't gone more than a mile when we came under heavy shelling.

One shell burst under our truck, blowing the bottom out and smashing the

front axle and the offside wheel. The only thing that saved us was the

soldiers' packs and the ammunition boxes. Luck was with us. None of the

ammunition was hit and we all managed to get out safely and got down in

a ditch. The quartermaster then came to us and told us to get our mess

tins and go into a broken down barn where the cooks of another unit were

dug in. They gave us corned beef and biscuits and a mess tin of nice hot

tea. By now my feet were feeling better, so I went with a few more to

bring the wounded their meal. We stopped there about five hours then moved

off again, but we had to leave the wounded who couldn't walk because we

hadn't any more transport.

We'd gone another four miles when we stopped near a farm for a rest. Most

of us had no drinking water, so me and a bloke called Jim Hacking who

came from Royton near Oldham went to the farm with six water bottles each

and we were met near the door by the farmer's wife who must have known

what we wanted. She let us come in and fill our bottles. Then she filled

a bucket and followed us to the ditch and let the others fill theirs.

Just then the officer came and had a word with her. He told us that she

would make us some tea and coffee if we could stay, so me and Hacking

went back with her and waited in the kitchen until it was made, and whilst

we were waiting she gave us two big slices of home-made bread with jam

on. It was the best thing I'd eaten since my wife sent me the cake. It

tasted lovely!

The tea was in a bucket and there was coffee in another. I offered to

pay her, but she shook her head to say no. When we got back to the ditch,

we had no sooner started to dish the stuff out than Jerry started to shell

us. This was the worst shelling we had experienced so far. Most of the

shells were dropping in the fields amongst the cattle, killing them. We

lay flat in the ditch for a good ten minutes, then we got up and started

to take the buckets back, but we had only just started across the field

when a shell came over and hit the farm buildings. Then another one dropped

in front of the farmhouse and started a fire. When me and Hacking heard

the shells coming over we dived flat on our faces. We lay there for a

bit, then I got up and looked at Hacking who was still lying there. He

said he had been hit in the shoulder and the elbow. I helped him to his

feet and saw part of his elbow had been blown off and part of his shoulder.

A couple more lads had also been hit, but only slightly wounded. I called

out to the lads to get the M.O. and I helped to get Hacking down onto

the road where he could be put on a truck and attended to. It didn't take

them long to get him on a truck. I took his rifle and ammunition and another

lad carried his webbing equipment, and another his steel helmet.

Then we were off again. This time to a small mining village where we dug

big tank traps across the streets and, with the Royal Engineers, we dug

more trenches where the engineers laid explosive charges and waited for

the enemy to show himself. During this operation we heard a lot of planes

going over and looking up we saw about twelve German bombers. I thought,

here we go again, another bloody bombing. It never seemed to stop. We

had been bombed and shelled every day for over a fortnight, and had never

seen any of our planes since we left England. Then, instead of bombs coming

down, we saw they were leaflets, hundreds of them. I picked one up and

it said: "Englanders, lay down your arms. You're surrounded. You

will be treated as brave soldiers. Your Belgian allies have given up and

laid down their arms and also the French are falling back on all fronts.

If you don't lay down your arms now you will be taken prisoner, or annihilated."

Things looked very grim. We were in a dangerous position. The Belgian

troops, who were on our left, had thrown down their arms leaving our left

flank open to a German attack, which could cut us off from the rest of

our troops. On our way to the coast we came across more units as bad as

ourselves. They were all mixed up. All making their way to the coast.

We met a French artillery battery in action. They were using all their

ammunition up and then blowing the guns up. They were also shooting their

horses. For miles and miles, in fields and on roads there were smashed

trucks, guns and all sorts of military equipment. We also met a battalion

of French infantry digging trenches. They looked to be in a poor condition

but they were all drinking wine of some kind and eating bread. As we passed

the Frenchies we met a bloke from the Royal Navy who was looking for his

brother who was serving with the Royal Warwicks. We told him they were

in positions further back, near to the town of Kemmel, but that was yesterday,

they could be anywhere by now, things were moving so fast. We asked him

how far it was to the coast and he said about seven miles. He also told

us that there were thousands of troops trying to get out of the French

port of Dunkirk - the navy and all kinds of craft. Well, we left him looking

for his brother and continued towards the coast. We were all on our last

legs and it was here that I had to go and relieve myself in a ditch. I

had dysentery badly, and whilst I was there another of my mates came looking

for me. He was the same, suffering from dysentery. His name was Pat Walton

and he came from Bury. He was after a cigarette and a match. He looked

terrible. He had been in a shell hole with two dead French soldiers. One

had no face and the other had half his side blown away.

I didn't have any cigarettes or matches, so we walked on a bit with a

lot more of our blokes, and we saw a signpost saying Dunkirk. I said to

Pat,

"Look, we're nearly home!" He said,

"I bloody well wished we were. Bugger this for a lark!"

Later, we came across a French soldier who looked to be asleep against

the bridge wall. Pat went over and asked him for a cigarette, but got

no answer. So Pat just touched him and he fell over. He was dead. We looked

him over but couldn't find any marks on him. He must have been killed

by the blast from a shell. Anyway we looked through his pockets, but could

only find a pipe and some tobacco and a few matches. Pat lit up first

and nearly choked, then I had go and I nearly choked.

It was here that we had to form up into our platoons to see who was missing.

We had some that were wounded taken on trucks and a few that had dropped

out on the march. After the roll call we stopped at a deserted farm. It

had got dark, so we took up defensive positions for the night. It must

have been about three o'clock in the morning when one of the platoon sergeants

came round and told us to get ready to move and not to make a noise, but

to follow him in single file. He said we were going to the beaches at

De Panne near Dunkirk.

In the dark it was murder trying to miss walking into things the other

troops had left behind. Now and again you stumbled over a dead bloke or

tripped over barbed wire or fell into shellholes. In the meantime, up

on our right near to Ostend, we could tell there was a big battle going

on by the noise and flashes of gunfire. Every minute it sounded to be

coming nearer. We managed to get to the town of De Panne and make our

way down to the sand hills where we just dropped exhausted.

The first thing we did was to dig shelters. A few of us went looking for

doors and other things that would make a roof. We went into houses that

had been damaged by the shelling and came back with roof timbers, doors,

and tins of sardines. One bloke brought back an army pack full of potatoes

and another bloke brought a pile of pillows to make sandbags. Then we

all mucked in, some filling sandbags and making a dug-out and others peeling

spuds and boiling them in a bucket that we found.

Later on Sergeant Gale from our

platoon told us to try and find some of our lads who hadn't turned up

and our company officer also sent a runner to get in touch with C Company

of our Battalion, which was in positions over the bridge in Rosendael.

We had got down to the farm where we started from, when Jerry started

shelling again. There were a lot refugees sheltering in a barn, and an

officer from a signals unit told me to give my emergency ration to some

children who were screaming and frightened of the shelling. These rations

were designed to feed a soldier for forty-eight hours when no other food

was available, and you weren't allowed to eat them without an officer's

consent.

Well we had travelled about a mile when we spotted nine of our lads; one

was being helped along by two of his mates. They said they just managed

to get out of Rosendael before the Germans broke through, and it was there

that they'd seen Private White, the runner whose home was in Skipton,

talking to an officer of C Company.

We started back and came down onto the sands. There must have been ten

thousand troops at the beach and long lines of troops up to their necks

in the sea all waiting to get on boats. We later met our officer who told

us to try and keep together but if not, to make our own way to the boats.

"Good luck to you all," he said. Then we went up to our dugout

and we were given some boiled spuds and a sausage each, washed down by

a mess tin of tea. Next to us there was a company of the Cheshire Regiment

and about twenty from the East Lancashire Regiment. We also saw two companies

of a Guards Regiment marching in step as though they were on the parade

ground.

Not long after enemy bombers came over dropping their bombs, mostly on

the town of Dunkirk and on the dock area, hitting a ship taking on troops.

Then German fighter planes came over us, machine-gunning troops on the

beach and those wading out in the sea to get to the boats. We were lucky

being in the dugout. Up on the promenade three heavy ack-ack guns opened

fire on the enemy fighters and hit one as it flew towards a ship loading

troops. We watched it crash into the sea, just missing a boat loaded with

soldiers. Everybody started cheering when they saw it crash.

Soon an officer came and asked us to help to get some wounded out of some

cellars and bring them down to the sea and help them onto the boats. They

had been blinded and their eyes were bandaged. There were about thirty

of them and some had other wounds besides being blind, but they managed

to walk. We left them to the care of some of the Medical Corps and went

back to the dugout. Soon after a bloke in our platoon came running to

us and said he had seen a ship's lifeboat stuck in the sand further up

the coast, and it needed a lot of us to get it moved into the water. Well

about twenty of us set off to try to move it, but it wouldn't budge no

matter how much we tried. So I said we should just sit in it and wait

until the tide came in and floated us off. We got in and waited a good

two hours, then the boat started to move, and me and a few more lads got

out and started to push it into deeper water. The only snag was that we

hadn't any oars to row with, so those with rifles used those and the rest

with anything they had. Well we started off heading for a large ship,

but it was slow going, though we must have gone at least a mile when water

started coming in from the side. We were over-loaded and the rate the

sea was coming in I thought we would never reach the ship. Then those

of us with steel helmets started to bail out. One bloke in the bows from

our platoon called Collier who came from Doncaster started to panic and

said he couldn't swim, then somebody said,

"Well now's the time to learn!" Not long after the boat filled

up, and it was everybody for themselves. I thought the nearest ship was

too far away, so I started swimming back to the beach with the tide to

help me. Some more poor swimmers did the same, but a lot of them didn't

make it. We never saw them again.

During all this the enemy was knocking hell out of Dunkirk, setting fire

to buildings and the docks. Me and about ten more who had swum back started

to go towards Dunkirk when a Royal Engineer officer asked us to help him,

with some of his own men, to get some of the wounded onto a kind of a

makeshift pier that they had made by driving trucks into the sea and lashing

planks and doors to them to make it easier for small boats with shallow

draughts to come close. Well we started, with one of us at each side lifting

them up onto the jetty. Some of them were in a bad state, and looking

at some of the worst wounded made you wonder what future these young lads

had when they got back home. Some of them were blind, some had limbs missing

and others were shell-shocked. But they kept coming, and now and again

the bombers came over and dropped their bombs and went back for more.

We had been up to our waists in water and sometimes up to our necks for

hours when the officer told us that it was time for us to try to get a

boat. He thanked us for our help in getting the wounded away and we started

to go back to our dugout, and some of us went into De Panne looking for

food and something to drink.

After a short while we heard a lot of singing coming from a cellar. We

went down and found about a dozen blokes from the Lancashire Fusiliers,

drinking wine from bottles, and there in the middle of the floor was a

big pan of corned beef stew. There were also two lads out of the Lincolnshire

Regiment who had been wounded right back in the action at the bridge in

Oudenaarde, where we had run before the engineers blew it up. Well, they

were glad to see us. Our regiment was the King's Own Royal Lancaster Regiment

and some of us had served with the Fusiliers, so they said we could join

them and have some grub and some drink which they had found in a wine

shop. Nearly everybody had filled their big packs with the stuff, and

also hundreds of cigarettes. We had a good couple of hours down in that

cellar. Then we decided to try our chance at getting a boat, so we set

off down the beach and looked out to sea.

The time was about ten o'clock at night when, in the distance, a destroyer

started signalling to us to wade out as far as we could and they would

try to pick us up. Well we set off, but we hadn't got far when Jerry started

shelling the boats. Then the destroyer which had been signalling turned

and headed out to deeper water. When she was out of German shelling range,

she turned again and started to shell the enemy guns. Then, after a quarter

of an hour the shelling from the Germans stopped and the destroyer turned

again and came to pick us up. She stopped and lowered two of her lifeboats,

manned by four naval ratings, who came and pulled us into the boats then

one of them towed the other behind and went over to pick up some more

troops who were waiting, up to their necks in water. We arrived at the

destroyer and had to climb up nets, which was hard and difficult when

carrying a rifle, ammunition and equipment. I got to the top of the scrambling

net and a naval rating grabbed me and pulled me over the side. He told

me to get below to the engine room.

When I got down there the place was packed with troops, some fast asleep

and exhausted and some covered in oil from sunken ships. I looked around

for a safe place to sleep and found a spot close to a steel ladder that

went up to the deck. I thought it would be handy if we should get hit.

Well the next thing that happened was a rating came round collecting our

rifle ammunition for their twin Lewis guns that they were firing against

low flying enemy aircraft. After that another rating came round with two

buckets of hot tea laced with rum, which warmed us up. It wasn't long

before I was fast asleep, then all at once there was a hell of a bang.

The ship's guns had opened up. Some of us went up on deck to see what

was happening. The enemy artillery was firing at ships leaving Dunkirk

loaded with troops. Some had been bit and were on fire. I saw the ship

that brought our battalion to France from Southampton hit by a number

of shells, and later a dive bomber dropped a bomb down one of her funnels

and blew parts of her boilers out of her starboard side. Luckily she hadn't

picked up any troops, but the crew must have suffered looking at the state

she was in as we got underway.

That was just after midnight on Saturday 2nd June 1940. I saw the town

of Dunkirk in flames and heard loud explosions, caused by the Royal Engineers

blowing up oil tanks and other installations. Well we were still on action

stations and making good speed. One of the ratings I was talking to, who

came from Stockport, said that if everything went to plan we should be

in Dover by about six o'clock. We were going along nicely when all at

once the ship came to a stop and all the lights went out except the torches

that the crew had. Then a ship's officer told us the reason we'd stopped

was that there was a German bomber overhead. We had stopped because if

the ship was moving he would see the ship's wake. A bit later when the

bomber had gone we got underway again. It was just breaking daylight when

we caught up with a trawler, overloaded with troops. Some of them were

wounded so we hove to and started picking some of them up - at least forty.

The skipper thanked us and asked our captain if he would escort them to

the nearest port. The captain said he was going into the port of Dover

and should be there in about two and a half hours time, but we reduced

our speed so the trawler could keep within sight of us and by the time

we got to Dover it was nearly six thirty on Sunday morning.

What a grand sight it was to see the docks, full of all kinds of ships

though mostly naval craft. To get to the quayside the ship had to tie

up to the next destroyer on our port side and to reach the quay we had

to go over four other naval craft. It was like a football match loosing.

There must have been a thousand of us making our way the best we could,

some helping a wounded mate, others being carried on stretchers with labels

pinned on them, stating the kind of wounds they had.

I went with the crowds to the railway station and lined up at a lot of

trestle tables which were full of sandwiches and cakes and pots of lovely

hot tea given to us by the Salvation Army, God bless them. They also gave

each soldier a packet of cigarettes and a box of matches, and a field

service card which you just had to put your name and home address on saying

that you had arrived in England safely.

The train we got in was a steam train. All the wounded were put into special

coaches at the rear of the train and after waiting about half an hour

we pulled away, not knowing our final destination. The first place we

stopped at was the historic town of Bath. Here we were given more drinks

of tea and sandwiches and also a packet of Player's cigarettes each. Then

they took the wounded off and transferred them to waiting ambulances to

be taken to hospital in Bath. After things had settled down we then proceeded

to a place called Tenby on the South Wales Coast. We arrived there round

about six p.m. Sunday 3rd June after leaving Dover, which had taken us

over eleven hours. We were then ordered to fall in onto the platform in

three ranks by a sergeant major from The York and Lancaster Regiment,

who was all spit and polish and a voice like a foghorn. Because some of

us couldn't fall in to his liking he got a bit annoyed and told his sergeants

to put them on a charge. Well that did it. We all shouted,

"Bugger off and polish your brasses! That's all you bloody lot's

fit for!" Then an officer who had been with us at Dunkirk took charge

and told the sergeant major that he would be responsible for the men and

would see that they were taken to the camp at Penally, about two miles

away.

We started to march the best we could, some of us in all kinds of clothing

that the Salvation Army had provided us with. We were all dead beat, and

ready for a good sleep and a bath. We hadn't had our clothes off for five

weeks and most of us were lousy and in need of fresh under clothes and

uniforms. On our way to the camp hundreds of people lined the streets

cheering, and some were crying when they saw the terrible state we were

in. We came into the camp in small groups and when we had all arrived,

we had to fall in and the camp commander gave us a short talk about the

camp and told us that food was ready in the large building and the canteen

was open until midnight as well. The bell tents that were erected were

sleeping quarters for six occupants and reveille was at seven a.m.

Well the first thing I did was to go for a meal. It was a big potato pie

with red cabbage followed by rice pudding and a pot of hot tea. It was

nice to sit at a table instead of sitting on the ground or queuing in

the rain for your meal. After that satisfactory meal, I went looking for

my mates - Pat Walton, Tom Duckworth and Jack Bolton, and a Lancashire

Fusilier who came from Todmorden. We found a tent and turned in for the

night. It was grand to get our boots and clothes off and to have clean

sheets and blankets to sleep in. As soon as my head touched the pillow

I was unconscious. It was sheer bliss. I hadn't slept so long in my life.

Some got up for breakfast, but it was dinner time when I woke up and after

getting a good wash I felt grand and refreshed.

I just managed to get some dinner, then it was on parade again. This time

to give your name rank and number, then your home address and next of

kin, then the name of your Regiment. After all that we had a medical and

then went to be deloused. We were then issued with new clothes and webbing

equipment, after that we were paid and given passes and travel warrants

for fourteen days leave.

After being inspected we marched down to the station. There were some

who lived near and didn't need a train, but most of us were from the northern

counties and also the Midlands and London areas. Well it must have been

about an hour before a train came and about three hundred of us caught

it. It stopped at ten stations before we arrived at Swansea, then we changed

and continued on a faster train which was a corridor train, packed with

troops and naval ratings. The next stop was at Llandeilo then Llandovery

and Llandindrod Wells; then on to Shrewsbury where we stopped for ten

minutes to change drivers, then off again, stopping at Whitchurch then

Nantwich and then Crewe, where we had to change trains for Manchester.

Here a lot of the troops who had been at Tenby had to report to the Regimental

Transport Depot on the station for information concerning where we had

to report after our leave expired. All the 9th King's Own had to go to

Barmouth in Wales.

The train was crowded with military personnel as we pulled in at London

Road Station and those who were going towards Bacup walked down to Victoria

Station. Here we had to wait about twenty minutes, so we all went into

the station buffet for a drink of tea. There were twelve of us for the

train - one for Whitefield, four for Bury, three for Ramsbottom, one from

Waterfoot, me from Stacksteads and two from Bacup. As the train was entering

Stacksteads station, my brother spotted me as he was filling coal from

a railway wagon, and shouted to me to meet him on the coal siding before

I went home. A few people came and shook my hand and said they were glad

to see me, and asked me what it was like. Well I said it wasn't so bad.

There were a lot never came back, so I'm one of the lucky ones, thank

God. I managed to see my brother Fred and he gave me a good hug and took

me for a home coming drink in the Railway Tavern next to the station.

The landlord whose name was James Flanagan welcomed me with open arms

and treated all of us to a drink. Then my brother said it was time he

got back to work, so we came out of the pub and he went back to filling

coal sacks and I came home and gave them all a big surprise. It felt grand

to be back and to see Alice my dear wife who I hadn't seen since my last

leave, which was nearly three months before when I was at Ripon Camp.

Everybody was glad to see me and I to see them. I had a smashing leave,

but unfortunately good things come to an end and after a few goodbyes

were said, l returned to my unit in Barmouth.

Here we were made up to fighting strength and the battalion was split

up. Each rifle company was scattered in different parts of the town. Our

company was across the bar estuary in the small village of Fairbourne,

the place where the Ghost Train film was made. Well after we were settled

in our billets, which were in people's houses, the battalion was paraded

on Barmouth promenade and our commanding officer spoke to us all, thanking

us for the courageous and splendid way we had conducted ourselves in the

action we had been in. Then, after being inspected, we marched to the

parish church for a thanksgiving service for our safe deliverance. It

was a very moving service, the Last Post was sounded by one of our buglers

and the hymns were played by the regiment's band, whose job in action

was to serve as stretcher bearers.

The battalion got reinforcements from the Lincolnshire Regiment and some

from the South Staffordshire Regiment. Two of the Lincolns were in my

billets so we made friends right away and we went everywhere together

unless we were on different duties. Whilst we were here, we did a lot

of firing and route marching to the coastal town of Harlech, which was

eleven miles away. We also did guard duties on a French flying boat which

was anchored in the bay. After three weeks the battalion was ordered south

to Bournemouth on the south coast.

It was one night as I was doing headquarter guard there, that a large

German bomber force came over, dropping bombs and also parachute mines.

Our guard-room was in the lounge of a big mansion in Charnley Chine in

Bournemouth and all at once there was a tremendous explosion. I dived

flat under some bushes in the garden. Then I heard windows being blown

out and parts of the roof of the house coming down. After the raid was

over, I got up and went in the guard-room to see how the rest of the lads

were. What I saw made me laugh. The lads looked like the Black and White

Minstrels because of the soot falling from the smashed chimney and the

plaster that had come down when the large ceiling collapsed. Luckily no-one

was injured in the raid, though later we heard that a large mansion further

up the Chine had been completely demolished by a parachute mine and twenty-eight

soldiers of the East Surrey Regiment had been killed. They were later

given a military funeral in Winton Cemetery, just on the outskirts of

Bournemouth. A small detachment from every unit in the immediate area

took part in the military parade, and today, fifty-five years after this

terrible incident, the local people still put flowers on their graves.

Things were quiet for a short time, but the people down there weren't

as friendly as up north. Only the Salvation Army did anything for us;

but for them we wouldn't have had anywhere to spend our bit of leisure.

I remember it was one Sunday night that me and my mate called Jack Owen

from West Bromwich called in a pub for a drink and a packet of cigarettes.

I think between us we had about five shillings. Well we got our drinks

and cigs and as we were sitting down at a table where an elderly couple

were sitting, Jack's respirator swung round his neck and accidentally

knocked over the couple's drinks. Jack said he was sorry and went up to

the bar and explained to the barman that we couldn't pay for the spilled

drinks, but on our next payday we would pay for the damage. The man whose

drinks Jack knocked over came and spoke to Jack and told him not to bother,

it was just an accident. He also asked us to join him and his wife and

said,

"We know you don't get much pay." We both thanked them but we

said we had to get back to our unit. So we left and went further down

the road. We hadn't gone far when we heard a lot of singing coming from

some kind of a school. I said to Jack,

"How about going in to see what's going on." Well we had just

got to the door when it opened and a young woman said,

"Hello. Would you like to join in the singing? There are some more

soldiers in and shortly there will be refreshments." We looked at

each other and said,

"Why not? There's nowhere else to go." So we ventured in and

joined in the singing of hymns. It was the Salvation Army who welcomed

us and told us to come again. There were one or two more of our lads joining

in the singing and between us we had a good do. We were each given a mug

of tea and a sardine sandwich and five cigarettes. Soon after it was time

for us to go and we thanked them for the refreshments and cigarettes,

and for the help they gave to me when I arrived at Dover from Dunkirk,

when they found me a good pair of boots.

The day after our company was sent further down the coast to Boscombe

and Southbourne and our platoon to Hengistbury Head where we started to

dig trenches and strong dugouts, and helped the Royal Engineers to erect

barbed wire defences all along the sand hills and the beach right into

the sea. The engineers also laid land mines, wired to each other and more

underwater obstacles. We had a small train pulled by a wire rope on pullies

to move anything heavy that we and the engineers needed. You see, the

positions we were in were among large sand hills and not suitable for

vehicular traffic.

There were a lot of enemy aircraft in the area and one night as we were

standing looking out to sea over towards the lsle of Wight, we could hear

a lot of anti-aircraft fire and see the searchlights looking for the enemy

planes. Then we saw in the distance about fifty German bombers heading

towards Southampton, followed by night fighters. It wasn't long before

we heard the crashing of bombs and the anti-aircraft guns firing. After

about two hours we heard then returning, but only in small batches. I

remember one enemy bomber that never made it back to Germany. It came

right over our positions heading out to sea. One of our fighters was on

his tail and shot the Jerry down. As soon as it hit the water it blew

up, scattering wreckage all over the place, some just missing our trench.

A few days after the bomber crashed we noticed one morning as it was breaking

daylight that something was hanging on the wire in front of our positions.

After another look we saw that it was an airman with his torn parachute

entangled in the barbed wire. Our sergeant at once told the officer in

charge of the engineers what we had seen, so with two of his men carrying

wire cutters and a plan of the mines they had laid on the beach, they

went slowly down, taking extra care until they got to the body hanging

there on the wire. After studying it for a while, the men started cutting

the wire until he was finally released, then between them they carried

him up to where the little train was and laid him onto some duck boards.

He looked all bloated and green and when they turned him over his back

had about twenty bullet holes in it. They looked through all his pockets

for anything that they could find that was of military importance and

also to find out his identity and the name of his unit. After they had

satisfied themselves they took him away for burial - I think in the cemetery

in Christchurch.

We manned this coast for another two months, then the battalion moved

to Littlehampton on the West Sussex coast to man the concrete pillboxes

that extended from Bognor Regis to Worthing - a distance of fifteen miles.

Our platoon manned two large pillboxes, one at the mouth of the river

Arun and the other one at Rustington. All the beach was mined and three

rows of barbed wire were laid in the sea. Behind us was the small promenade

and a number of bungalows. One of them was the home of the well known

actor and comic Arthur Askey, who had had to leave his home like all the

other people who resided near the coast. The only persons allowed near

the coast were the military and we were expecting the Germans to attempt

to invade any time, so we had to be vigilant night and day.

Just about fifty yards distant from our pillbox was a six-inch howitzer,

manned by ten gunners of The Royal Artillery, who, when not on action

stations, slept and had their meals in a wooden army hut just behind the

gun. Well it was decided that whoever was on guard when it was time to

stand-to would waken everybody up. This particular morning it was my turn.

I don't know to this day what made me wake the lads up a bit sooner, but

it was lucky I did. If I hadn't they would have all been killed, because

out of the morning mist came a low flying enemy bomber and dropped a bomb.

I think he was after blowing the gun up, but missed and hit the army hut,

blowing it to bits. In the meantime everybody jumped down into their trenches

I dived into the pillbox to join my mates. Lucky I did, because after

it was all over I had a look at the damage the bomb had done and there

was nothing but a pile of smashed timbers that was once an army hut. All

the gunners' kit and their personal belongings were gone, as well as the

place where I'd been standing near the pillbox, which had large chunks

of concrete broken off by the blast. Well after we had cleaned things

up our officer came and. asked us if we were all okay. Then he told us

to keep a good look out for two motor torpedo boats who would give us

a recognition signal, which, if there was fog, would be two short blasts

on their fog horn and if visibility was good, they would signal us by

flashing two flashes or by calling us on their loud hailer.

It was getting a bit lively all along the south coast. The Battle of Britain

was being fought and every day enemy bombers came over us - some heading

towards Portsmouth and some trying to bomb the three Royal Air Force bases

which were at Ford, Tangmere and Angmering, all within a twelve miles

radius of Littlehampton.

Nearly every night, if visibility was good, we watched our bombers going

out over the English Channel to bomb targets in Germany and the occupied

countries. We used to count them going out and watch them returning in

the mornings. Sometimes they used to come home badly shot up, and in twos

and threes, but one morning we saw one limping home with a German fighter