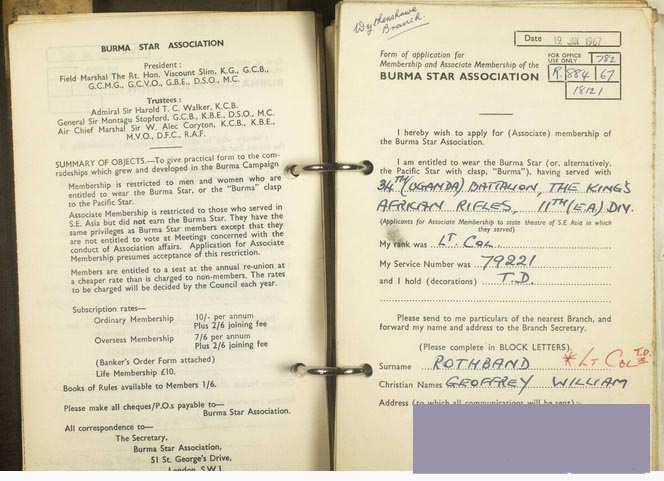

Lt Col G W Rothband TD

Geoffrey Rothband joined the Lancashire Fusiliers in December 1938 and was commissioned shortly afterwards.

He joined the 1/5 Battalion XX

The Lancashire Fusiliers (TA), and in early March 1940 the 1/5th embarked

with the BEF at Southampton for Cherbourg in France.

Following the evacuation of the BEF from Dunkirk the Bn regrouped in England.

He left England in December 1940 and joined the 1st Bn in India and served in the Far East in Burma and with the Kings African Rifles in 14th Army, before arriving back in the UK in May 1945.

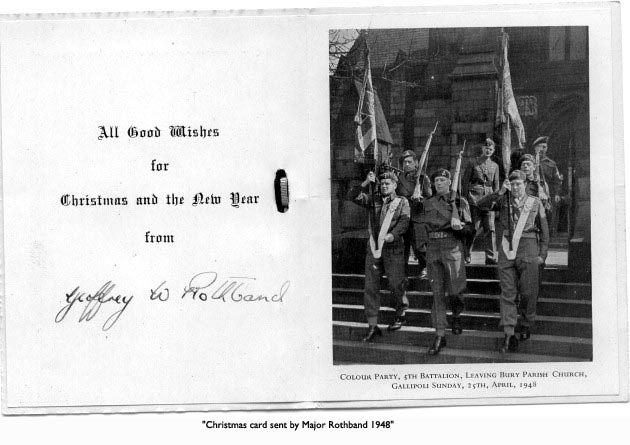

After demobilisation, he rejoined the 5th Bn The Lancashire Fusiliers when the Territorial Army re-started in 1947.

In 1959 he took Command of the

5th Bn Lancashire Fusiliers, a command he held until 1962 when he finally

ended his service.

/8FDE4A709BFE11DBA509152E52009091.jpg)

Dennis Laverick's dad 3rd from left front row

WO and Sgt Mess Lt. Col Rothband center of front row

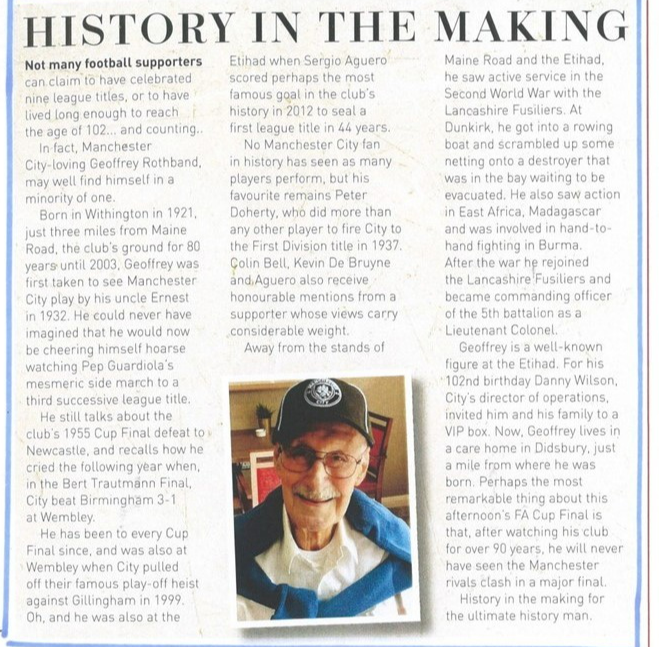

Lt Colonel Geoffrey Rothband T.D. Age 94, interviewed on 20th March 2015

A Manchester man through and through, Geoffrey Rothband followed in his father’s footsteps enlisting in the Lancashire Fusiliers peacetimeiers in 1938. Seeing combat throughout the war from Dunkirk to Burma via East Africa and Madagascar Geoffrey remained in the service in commanding a Territorial Battalion of the Lancashire Fusiliers through to 1962, reaching the Rank of Lt Colonel and being awarded the Territorial Decoration for long service.

Geoffrey was interviewed at his home in Manchester on 20th March 2015

Geoffrey, Tell me a little about your family background. In 1914 my father enlisted in the Lancashire regiment. He was second in command of a rifle company, was wounded in the trenches in 1916 and invalided home. His brother, my Uncle Jack was killed in battle in the trenches just after the battle of the Somme, he was 37.

My mothers only brother, Lionel Franks went to live in Hull. Lionel joined at 18 to the East Yorkshire Regiment, went to France as 2nd lieutenant with the 8th battalion and was very severely wounded at the Battle of Arras in April 1917. He had only been in France three weeks. Lionel was taken to hospital in Rouen, his parents got to the hospital and spent three weeks holding his hand watching him die. There wasn’t a rabbi available when he died and he had a Christian funeral.

In WWII my father was pulled out of his office when the Germans were approaching the channel ports and asked to form a battalion of local defence volunteers. Father resigned his presidency of the Synagogue and formed the 46th Battalion (South Manchester & Withington) which he commanded until the Home Guard stood down.

When asked why he resigned the presidency of the Synagogue he said “I’d rather try to stop the enemy at the gates of the city than on the steps of the Synagogue”

I went to a school called Oundle. There were only half a dozens Jews at the school; some cousins on my mothers side had been to Oundle before me. I joined the Officer Training Corps and happened to be fascinated by the army section, I took to it like a duck to water for some reason. I left school in 1938 and a few months later I wandered along to Bury to join the Lancashire Fusiliers my father’s old regiment.

We went to France with the battalion and we took part in the withdrawal, the rout, we finished up at Dunkirk, we were lifted off the beaches at La Panne slightly east of the Dunkirk mole. We got into a lifeboat, I rowed out with ¾ of my platoon and we arrived at Ramsgate or Margate I don’t know which.

We reformed in Yorkshire and then a number of us were plucked out to go to East Africa so I joined two hundred 2nd Lieutenants in Blackpool, in boarding houses waiting for a convoy. After weeks in Blackpool we were taken in convoy to East Africa round the Cape. Encountered a German pocket battleship on Christmas day 1940, the only thing I remember is we saw a New Zealand light cruiser rushing through the centre of the convoy laying a smokescreen, the convoy scattered and we got to Freetown.

We were allowed ashore at Freetown and were arrested, we were 10 minutes late back on ship and we got a bollocking from the OC Troops. We went further on to Durban, were allowed 4 days ashore in Durban where I fell madly in love with a girl called Audrey Duncan I met in a restaurant. Look I was age 19, what the hell you know.

On to camp outside Nairobi where we were parcelled out to the various battalions of the East Africa Command, which was expanding like nobody’s business as part of the East African British, colonial forces, the Kings African Rifles.

When we got to Nairobi and I was given a platoon of reinforcements was sent to join the 3rd/4th Battalion of the Kings African Rifles in Southern Abyssinia. The Kings African Rifles were colonial forces with British officers, British senior NCOs and African soldiers.

I drew some vehicles and rations to drive to Mega (Ethiopia), hundreds of miles north through the Chalabi desert, I was in a strange country with African troops I had learnt Swahili on the boat going out because we spoke Swahili in the East African Command. Somebody said for Gods sake take some water, so I went to the depot and got hold of a 44 gallon metal drum and piece of hose pipe. We had to take water with us, I didn’t realise that. So we drove, it took 3 or 4 days, I didn’t know the African bush at all, I managed to speak Swahili but these fellows must have thought we were idiots.

We pushed into Abyssinia for some time meeting some of the Italians who had invaded Abyssinia in 1936 because Mussolini had to show Hitler he was strong as well, so he got a piece of Africa as well as Hitler.

In Abyssinia the East African forces job was to clear the Italians out and let Haile Selassie the Emperor back onto his throne in Addis Ababa. You see Haile Selassie was an Emperor in name only, he didn’t control the place it was full chiefs, he only controlled round Addis Ababa, if that. We recaptured British Somaliland from the North East, a couple of British Indian Divisions came in from the Sudan, and we came up from the south through the straights of Bab-el-Mandeb to a port in Eritrea on the Red Sea, a terrible place called Massawa, we called it the arse-hole of the Italian empire.

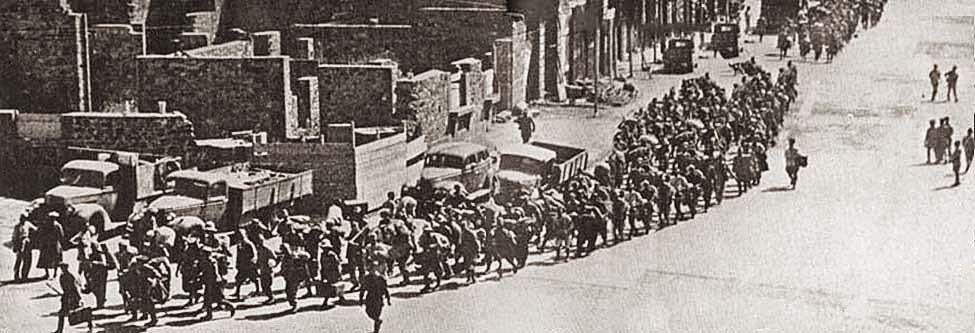

We were brigaded with two other battalions as part of the 11th East African Division and we went inland and positioned ourselves against the last Italian held fort in North West Abyssinia called Gondar.

We were formed up, two battalions forward, one battalion rear and we attacked this fort of Gondar which had 30,000 Italian troops in it. As we formed up on the start line I do remember the fellow next door to me got a bullet through his head, must have been a sniper. We started a long advance over open ground, hilly grassy. An Italian artillery shell landed, a small one 4.7 inch, it fizzed like a firework not going off properly, if it had gone off I wouldn’t have been here, several of my mates wouldn’t have been here. A bit further on I saw a wire, so I told the company signaller, give me a telephone and strip the wires, I plugged in and there were two Italians, we used to call them Wops, the Italians were Wops, two Italians very, very excited conversation. I cut the wire.

As we approached the fort, the whole lot, all the Italians came out with their hands up. They were all put into sort of cages, barbed wire, temporarily and they pleaded with us to give them more barbed wire and stakes to make a Zuma so that the Fuzzy Wuzzys wouldn’t come and cut their balls off, which they would have done. We took up our position in the town garrisoning it because the war there had finished, the Italians were finished.

I saw our commanding officer Col Frank Clifton of the Royal Fusiliers standing looking at a group of bedraggled white women. These were the prostitutes who had been imported to service the Italian officers; we didn’t have that sort of thing at all.

I heard that another subaltern David Sloane of the Suffolk regiment, a territorial officer, had been given a 3 ton lorry and some rations and had been told to take these women to Asmara the capital, its about 200 miles to Asmara and it took him 3 weeks to get there and back, I don’t know what he did with the women on the way.

Italian prisoners marching through Gondar under escort

We then had an extraordinary drive from the Red Sea right down through Abyssinia, skirting Addis Ababa, we were hoping we would have a couple of nights in what was the capital, we didn’t, right down past Mount Kenya, into Kenya for training. After some year or so training we crossed to Madagascar where we had to take the Island off the Vichy French and hand it over to the De Gaulle French.

Very long island Madagascar, off the East African coast, 1000 miles long 300 miles wide. We pushed slowly, two brigades of the Kings African Rifles, a South African Brigade and an extraordinary all British Brigade, 1st South Lancashire’s, 1st East Lancashire’s, 1st Royal Scots Fusiliers, 1st Royal Welsh Fusiliers, all pre- war regular soldiers and that took some months.

Then back to Tanganyika now Tanzania for training and then over to Ceylon for jungle training because the Far East war had just started by then and it caught the British Army out because we’d done no jungle warfare at all.

While this was going on of course D-Day hadn’t started, we’d cleared the Germans out of North Africa and pushed into Italy but this was a new ball game. The training was sudden and it was absolutely frightful, traipsing in the jungle with a full set of equipment as part of an infantry battalion, the footsloggers. Very hot, very humid, thank God we didn’t wear tin hats like some of the other divisions, we wore Australian slouch hats, you did everything in them sometimes you’d even have to shit in them when there was no other way, when you were in a fox hole, it was another world you know, you can’t imagine actually, it was another world.

Malaria in the African war and Far East was rife , it would go through a battalion of 850 men and decimate them, out of action for 4 days, more malaria casualties than battle casualties. They brought in this Mepacrine stuff which you had to take and it stopped the malaria while you were taking it, you had to physically force each man to take his Mepacrine once a day. Of course when you came home the Mepacrine wore off, you got on the boat in Bombay and by the time you got home you started getting the malaria.

Then the whole East African division went to Burma. Nobody knows about Burma, it’s a most fascinating campaign. There were about 12 infantry divisions, ours, an East African division, two West African divisions, there were the Gold Coast Regiment and the Nigeria Regiment, the Sierra Leone Regiment and there were 6 or 7 British Indian Divisions.

A British Indian Division was two Indian or Ghurkha Battalions and one British Battalion, most of the gunners were British. The Indian Divisions had a very, very long and a very tough war.

We came in after the biggest battle of the Far East where the Japanese attacks on a place called Kohima Imphal (March – July 1944) were repulsed with a great loss of life, a hell of a lot of hand to hand fighting over 3 or 4 months when the British were supplied by parachute drops. Some of which fell into the enemy positions.

Our battalion spent 4 months in the combat area, no such thing as a line pushing through the jungle, just advancing to contact, keeping going up the bloody hills and the streams and God knows what until you bumped into the Japanese who were withdrawing slowly down the length of Burma and they weren’t going to give it up easily.

Rations came on four jeeps for the battalion of 800 men, up and down this track until it was too muddy for them and then the reserve battalion humped them up. When the monsoon was on we couldn’t have any transport, the jeeps would sink completely and then some poor battalion would have to corduroy the road behind you, lay these trees out of the forest and then the Jeep would go over it and then the Jeep would sink again so we were supplied by air for long periods. There was one occasion when the RAF were coming from China, hundreds of miles away.

We were on half rations or quarter rations for about a week and the only food dropped to us was tinned bacon. Now what would you do? Of course you bloody well eat it. You’ve got to laugh, well we laughed like a drain, the chaps knew I was Jewish and they laughed.

The rations were very good, apart from this bacon week, you had what was on your back, there were no beds, no weekends off. You were there the whole bloody time

So we were in our company positions carrying all our kit, we only took our boots off when we got to a stream or a river, you were in combat all the time if you like, you were in the forward area all the time so we slept fully dressed and as soon as we arrived at a position we dug, we had a small spade, so we were below ground, every day.

The Japanese were very brave, very brave indeed. Where we were was like a very thick wood, you could see through parts of it and you can’t keep 150 soldiers in a rifle company silent. The Japanese, having crept up and found our positions, they would shout out before they attacked “Hello Tommy, Tommy where are you?” They’d form a line of sorts and suddenly come charging at us. I’ve had them come up to me there (an arms length) on more than one occasion if you had a rifle you put a bullet in his belly, some fellas used their rifles as clubs you see.

And eventually we got down to a place called Kalewa on the river Chindwin. We were going down one track, the 5th Indian division were coming down a parallel track 40 miles away through the jungle, we could here their gunners, eventually after at least 4 months the leading platoon of our 11th battalion met the leading platoon of the Jat regiment of the 5th Indian army at Kalewa. The 5th Indian had been in the Western Desert, then they moved to Syria, then Burma, they were never stopping.

We formed up and did a river crossing of the Chindwin the whole of the East Africa Division had now arrived on the banks of the Chindwin, half a mile wide not terribly fast flowing but fast enough and we all got our orders to cross the river, the enemy were on the other side, not in large numbers, they were spread out, but they were there.

Crossing the River Chindwin.

We were part of the British 14th army and the staff had decided of course that we would eventually reach the river and need some boats so the Royal Engineers were cutting the trees down and making them into wooden boats, they got loads and loads of outboard motors from somewhere. This is the staff doing their job properly, supplying us at the right place at the right time.

And in the dead of night you crept through the

bushes with your face blackened with a mixture of rifle oil and mud. We

got into the boats, started the outboards and went straight across the

river, it took us a mile down stream. Pitch black. Can you imaging a battalion

crossing the river, pitch black and it was pitch black, its never pitch

black here, you can always see a town 20 miles away, trying to sort out

into Company’s and Platoons. We did it and we formed a bridgehead

and we pushed inland a bit, to keep the bridgehead out of range of Japanese

artillery.

The Bombay sappers and miners

behind us started to build a bridge. The only way for them to build this

bridge was with big box girders and they pushed a pontoon full of kapok,

a bloody great pillow that floated into the river and then pushed the

girder onto the Kapok pillow, then another Kapok pillow and another box

girder and screwed them together and then planked the floor.

The first week they did it a Japanese shell actually landed and buggered the whole thing up but they got across the river and a couple of weeks later we were told that we had done our job, 11th East African Division had done it’s stuff and would be withdrawn to rest behind the front in Assam.

I do remember when we finally pulled out, coming over the top of the hill and seeing the original crossing point. When we had crossed there was jungle and river, jungle and river. It took my breath away because a whole town had come up. Divisional HQ, Corps HQ, Corps engineers, all sorts of follow up units. A bloody great town, I just went good God. Anyway the night we pulled out, we were relieved by another division, the British 2nd infantry division and I was sitting on the perimeter at about two in the morning with a fellow who was a lecturer at Makerere College Uganda and another of our 3 inch mortar sergeants called Battler Harrison an old territorial Sergeant from the Loyal Regiment North Lancs. we hadn’t spoken for hours, there was nothing else to say, we were tired, we’d had enough, there was nothing to say. Eventually we saw a file of men in tin hats coming quietly passed on the track about 20 yards away and then another file of men on the other side of the track following them and all of a sudden Sergeant Harrison says “What fucking heap is that” and out of the darkness a very offended high pitched voice of some very keen young 2nd Lieutenant says “We are not a fucking heap, we are B company, 2nd battalion the Durham light infantry” as they passed through our position and continued on the track towards Mandalay, Rangoon and then the end of the war.

We were pulled out back to Assam to rest and a few months later our number came up we were due to come home. Quite a lot of the fellows I went out with on the boat originally were on the boat coming home, in fact one was a great friend of mine Peter Faulkner whom was a regular office in the Devonshire Regiment. I spoke to him a month ago on the phone. He finished up commanding the Devonshire Regiment and I finished up going into the family firm in Manchester. He continued in the regular army after the war, I continued in the Territorial Army after the war, because apart from the nasty parts I liked the army I was happy in the army,

I don’t know why, there was hardly any anti-Semitism at all. There are Catholics who don’t like Protestants you know and vice versa, we think we’re the only people who get it in the neck, but we don’t.

When I finished active service my rank was Captain,

I joined the Territorial Army as a Major and 12 years later I was given

command of a battalion in Bury, the 5th Lancashire Fusiliers. I was a

Lancashire Fusilier, my father was a Lancashire Fusilier. I had a regular

Adjutant and a regular training Major, all the soldiers and three Sergeant

Warrant Officers as a permanent staff. I commanded the battalion from

1948 until 1962. Of course in the TA were liable to be called up so it

was a genuine rank, I progressed from Major to Colonel. I was awarded

the Territorial Decoration so you can describe me as Lieutenant Colonel

Geoffrey Rothband T.D.

.

Do you talk to the younger generations of your family about your experiences To an extent but it’s another world and its history, my eldest son is interested , my younger son is interested. Actually a few months ago, my grandson, he went to Shrewsbury school and couldn’t continue in the OTC, he hurt his back playing rugger, he’s a smashing lad, he said to me a few months ago Poppa I want to hear all about it so we have had a few sessions just him and me. Surprising but he really wants to know.

My wife who was much younger than me and an absolute stunning beauty if I may say so, there she was a young girl when I became CO, she handled it wonderfully talking to the senior officers. The officers of the battalion couldn’t keep away from her, the non-Jewish officers. How do you explain the differences between a Major and a Regimental Colonel? She took it on board wonderfully.

Does the world today meet your expectations No. You see I found from an early age that I was a Tory. I came out of the war and was faced with this dreadful Atlee government, which in some ways did a lot for the working class, but I found these working class left wing cabinet ministers, how can we have any respect for these people and I was very disappointed with the number of people who were left wing and they irritated me and annoyed me.

Do you think the younger generations understand what you have experienced. They wouldn’t know anything about the war, that’s history. A few people are interested but very few. Its history

What legacy do you feel you leave. Nobody leaves a legacy, the only thing people leave if they die is a reputation, and that doesn’t last very long. The only thing I regret of course was the end of Empire, I knew it couldn’t continue but I regretted it. That’s me, I have no pretence.