|

Sergeant Alfred

Richards VC

The Gallipoli 'Lancashire Landing'

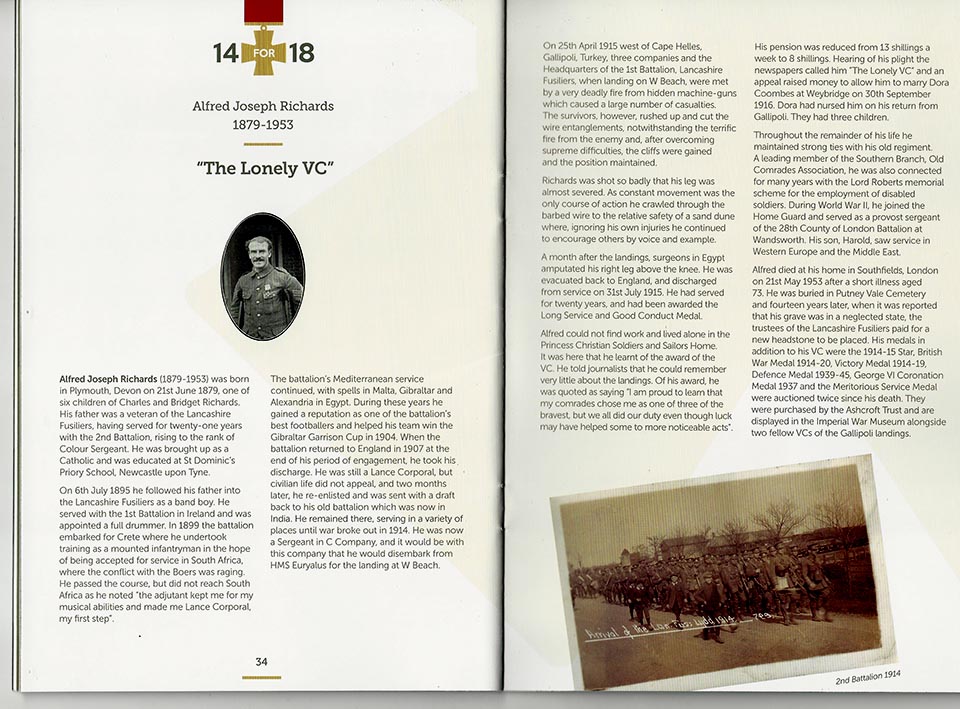

Victoria Cross Group of Seven to Sergeant A. Richards, 1 Battalion Lancashire

Fusiliers,

one of the famous 'Six Before Breakfast'

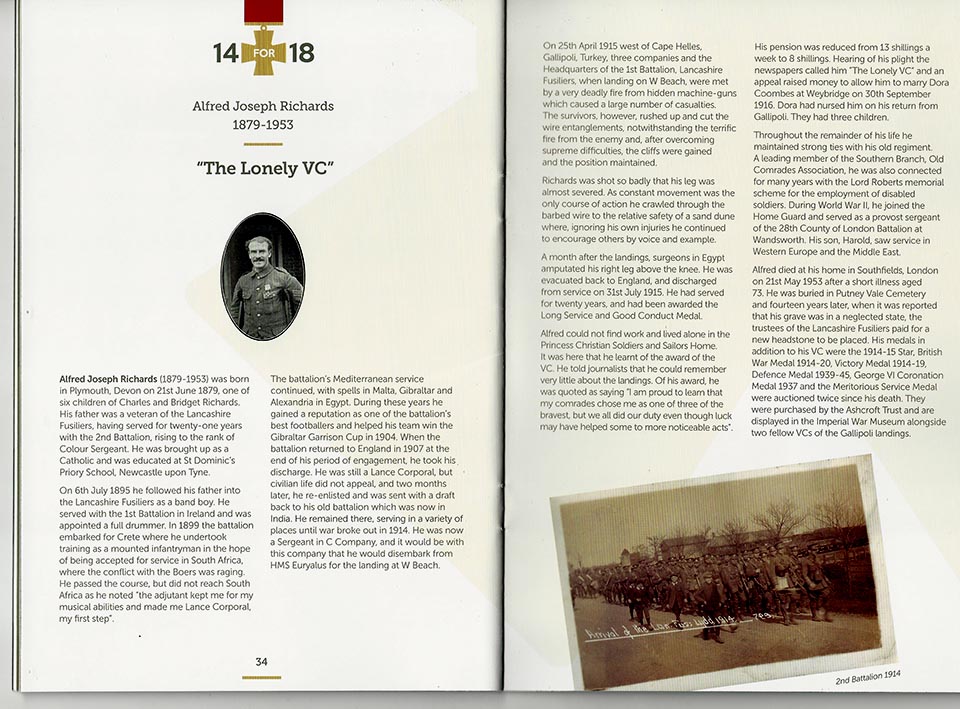

(a) Victoria Cross, reverse of suspension bar engraved 'Sergt A. Richards,

1st Bn Lancashire Fusrs', reverse of Cross engraved

'25 April 1916', the arms of the cross additionally engraved 'Sergt

A Richards 1 Battn Lancs Fusrs'

(b) 1914-15 Star (1293 Sjt. A. Richards. Lan. Fus.)

(c) British War and Victory Medals (1293 Sjt.A. Richards. Lan. Fus.)

(d) 1939-45 Defence Medal

(e) Coronation 1937

(f) Army Long Service & G.C., G.V.R. (1293 Sjt: A.Richards. V.C.

Lanc: Fus, the group good very fine

(g) A Silver Cigarette case (Hallmarks for Birmingham 1914), the outside

cover engraved

'Presented as a Token of Esteemed Regard to Sergt. Alfred Richards V.C.

1st Batn Lancs Fus

from the Sergts 7th (R) Batn Lancs. Fus. 3rd June. 1916.'

(h) Box for 1939-45 Defence Medal addressed to Mr A Richards, Southfields,

Wandsworth

(i) A quantity of original documents, including Certificate of Discharge

1906 and Character on Discharge 1907,

Certificate of Discharge from Second Enlistment 1915, 'Small Book' ,

various Certificates of Attainment, etc. (7)

Estimate ? 130,000-150,000

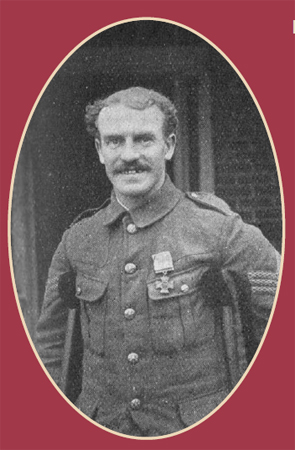

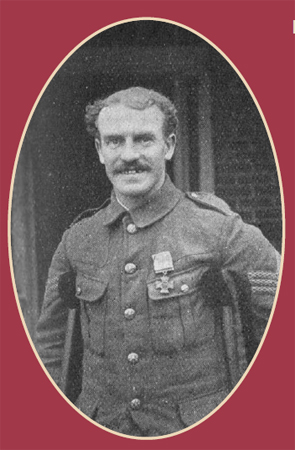

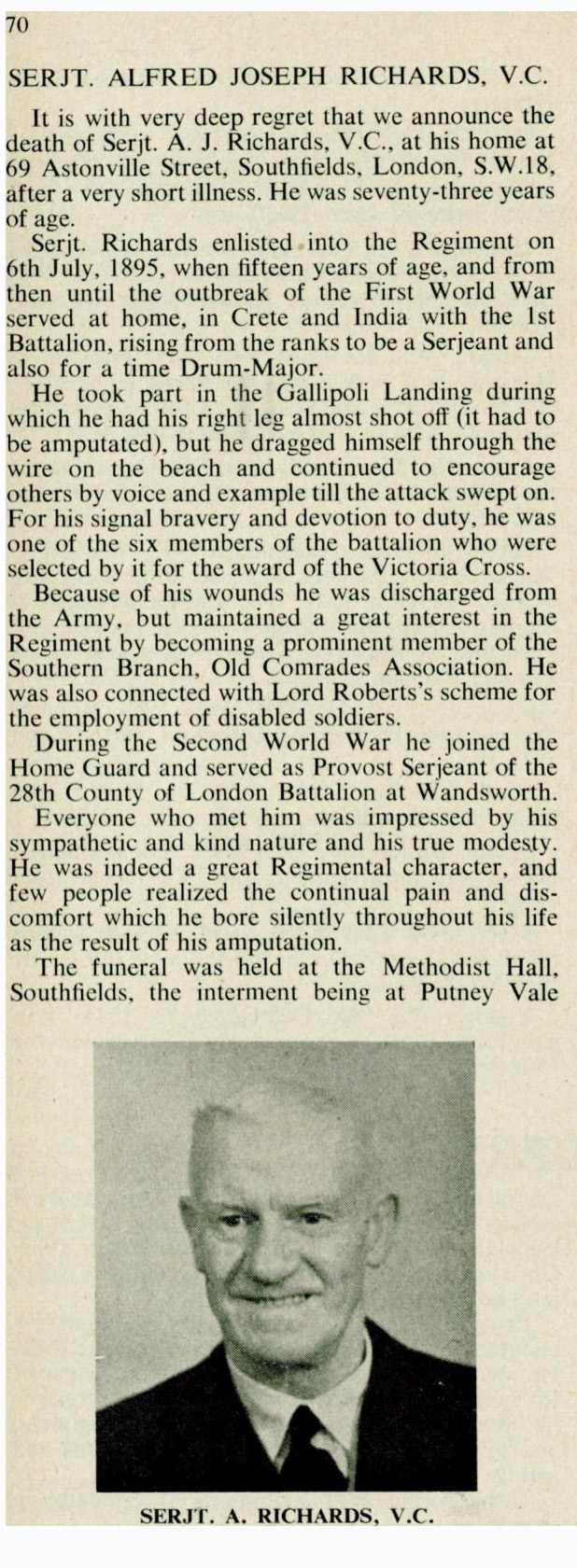

Sergeant Alfred Joseph Richards

V.C. born 25.8.1880 in Plymouth, Devon, the son of Charles N. Richards,

late Colour Sergeant, 2nd Battalion, 20th Lancashire Fusiliers; educated

at St Dominic's Priory School, Newcastle-upon-Tyne;

giving his trade as 'musician', he enlisted in the Lancashire Fusiliers

as a bandboy at Newcastle 4.7.1895,

and served in Ireland with the 1st Battalion, where he was appointed

full drummer; served in Crete, 1899,

and promoted to Lance Corporal; served in Malta, Gibraltar and Egypt,

returning to England in 1907;

after two months in civilian life Richards re-enlisted, and rejoined

his old Battalion in India; in 1915

the Battalion embarked for the Dardanelles, destined to take part in

the greatest amphibious

operation carried out during the course of the Great War. As the spearhead

of 86 Fusilier Brigade,

the Lancashire Fusiliers were to seize a small sandy cove lying between

Cape Helles and Tekke Burnu.

The cove, named 'W Beach', was well defended, the Official History stating

'So strong were the defences

that even though the garrison was but one company (3rd/26th Regt.) of

infantry, the Turks may well have

considered them impregnable to an attack from open boats'. The attack

was timed for 6.00 a.m. on 25 April 1915.

Any element of surprise was sacrificed in favour of a naval bombardment

of the enemy positions.

The landing was to become famous as 'The Lancashire Landing.'

V.C. London Gazette 24.08.1915

'Richard Raymond Willis, Capt.; Alfred Richards, No. 1293, Sergt.,

William Keneally, No. 1809, Private, 1st Battn. The Lancashire Fusiliers.

Date of Acts of Bravery: 25 April 1915.

On the 25th of April 1915, three Companies and the Headquarters of the

1st Battn. Lancashire Fusiliers,

in effecting a landing on the Gallipoli Peninsula to the west of Cape

Helles, were met by very deadly fire

from hidden machine guns which caused a great number of casualties.

The survivors, however, rushed up

to and cut the wire entanglements, notwithstanding the terrific fire

from the enemy, and

after overcoming supreme difficulties, the cliffs were gained and the

position maintained.

Amongst the very gallant officers and men engaged in this most hazardous

undertaking,

Capt. Willis, Sergt. Richards and Private Keneally have been selected

by their comrades

as having performed the most signal acts of bravery and devotion to

duty.'

Captain Clayton, who was killed

six weeks later, wrote: "There was tremendously strong barbed wire

where

my boat was landed. Men were being hit in the boats and as they splashed

ashore. I got up to my waist in water,

tripped over a rock and went under, got up and made for the shore and

lay down by the barbed wire.

There was a man there before me shouting for wire-cutters. I got mine

out, but could not make the slightest impression.

The front of the wire by now was a thick mass of men, the majority of

whom never moved again?.

The noise was ghastly and the sights horrible. I eventually crawled

through the wire with great difficulty,

as my pack kept catching on the wire, and got under a small mound which

actually gave us protection.

The weight of our packs tired us, so that we could only gasp for breath.

After a little time we fixed bayonets

and started up the cliffs right and left. On the right several were

blown up by a mine (It was in fact a British naval shell.)

When we started up the cliff the enemy went, but when we got to the

top they were ready and poured shots on us."

Major Shaw, who also did not

survive the campaign, wrote: "About 100 yards from the beach the

enemy opened fire,

and bullets came thick all around, splashing up the water. I didn't

see anyone actually hit in the boats, though several were;

e.g. my Quartermaster-Sergeant and Sergeant-Major sitting next to me;

but we were so jammed together that you

couldn't have moved, so that they must have been sitting there, dead.

As soon as I felt the boat touch,

I dashed over the side into three feet of water and rushed for the barbed

wire entanglements on the beach;

it must have been only three feet high or so, because I got over it

amidst a perfect storm of lead and made for cover,

sand dunes on the other side, and got good cover. I then found Maunsell

and only two men had followed me.

On the right of me on the cliff was a line of Turks in a trench taking

pot shots at us, ditto on the left. I looked back.

There was one soldier between me and the wire, and a whole line in a

row on the edge of the sands.

The sea behind was absolutely crimson, and you could hear the groans

through the rattle of musketry.

A few were firing. I signaled to them to advance. I shouted to the soldier

behind me to signal, but he shouted back

'I am shot through the chest'. I then perceived they were all hit."

Captain Willis, who led C Company

into the attack, later recalled 'Not a sign of life was to be seen on

the

Peninsula in front of us. It might have been a deserted land we were

nearing in our little boats.

Then crack! The stroke oar of my boat fell forward, to the angry astonishment

of his mates.

The signal for the massacre had been given; rapid fire, machine guns

and deadly accurate sniping opened from the cliffs above,

and soon the casualties included the rest of the crew and many men.

The timing of the ambush was

perfect; we were completely exposed and helpless in our slow moving

boats,

just target practice for the concealed Turks, and within a few minutes

only half of the thirty men in my boat were left alive.

We were now 100 yards from the shore, and I gave the order 'Overboard'.

We scrambled out into some four feet of water

and some of the boats with their cargo of dead and wounded floated away

on the currents still under fire from the snipers.

With this unpromising start the advance began. Many were hit in the

sea, and no response was possible,

for the enemy was in trenches well above our heads.

We toiled through the water

towards the sandy beach, but here another trap was awaiting us, for

the Turks had cunningly

concealed a trip wire just below the surface of the water and on the

beach itself were a number of land mines,

and a deep belt of rusty wire extended across the landing place. Machine-guns,

hidden in caves at the

end of the amphitheatre of cliffs enfiladed this.

Our wretched men were ordered

to wait behind this wire for the wire-cutters to cut a pathway through.

They were shot in helpless batches while they waited, and could not

even use their rifles in retaliation since the sand

and the sea had clogged their action. One Turkish sniper in particular

took a heavy toll at very close range

until I forced open the bolt of a rifle with the heel of my boot and

closed his career with the first shot,

but the heap of empty cartridges round him testified to the damage he

had done.

Safety lay in movement, and

isolated parties scrambled through the wire to cover. Among them was

Sergeant Richards with a leg horribly twisted, but he managed somehow

to get through.'

The Lancashire

Fusiliers had started the day with 27 Officers and 1,002 other ranks.

The next morning they numbered 16 Officers and 304 men.

Richards was evacuated first

to Egypt, where surgeons amputated his right leg above the knee, then

home to England.

He was discharged 31.7.1915, after 26 years with the colours. His discharge

papers read 'no longer fit for war service

(but fit for civil employment)'.

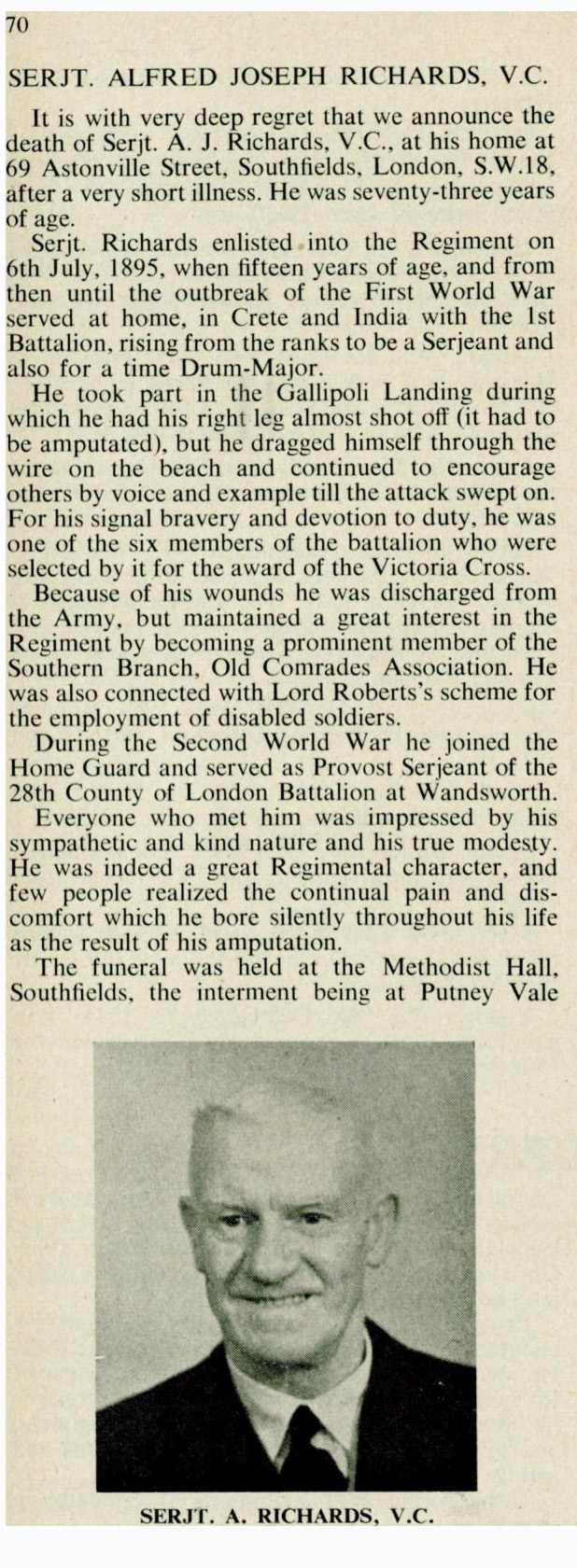

At the time of the award of

his Victoria Cross Richards was living alone at the Princess Christian

Soldiers' and Sailors' Home

in Woking. He had no family in England, and the newspapers referred

to him as 'The Lonely V.C.'

In September 1916 he married Miss Dora Coombes, who had nursed him during

his period of convalescence in Woking.

Despite his disability he remained an active member of the Regimental

Old Comrades Association and even joined the

Home Guard during the Second World War, serving as Provost Sergeant,

28 County of London Battalion.

He died at the age of 73 in Southfields, London, in 1953, and is buried

in Putney Vale Cemetery.

Joe

Omnia Audax XXth

|