Lieutenant General

Sir George Lea KCB DSO MBE

The last Colonel, XX The Lancashire Fusiliers

Lt Gen Sir George Harris Lea

and his wife Pamela |

Sir George Harris Lea, (1912-1990) was born on 28 December 1912 at Franche,

Kidderminster, Worcestershire, the eldest in the family of two sons and

three daughters of George Percy Lea, chairman of the family textile business,

and his wife, Jocelyn Clare, née Lea (his mother and father were

distant cousins). Educated at Charterhouse School and at the Royal Military

College, Sandhurst, he was commissioned into XX The Lancashire Fusiliers

in 1933. Lea was handsome, broad, and tall-well over 6 feet-a robust and

skilful games player, but a gentle and considerate man. He served in Britain,

China, and India with the Regiment before the Second World War.

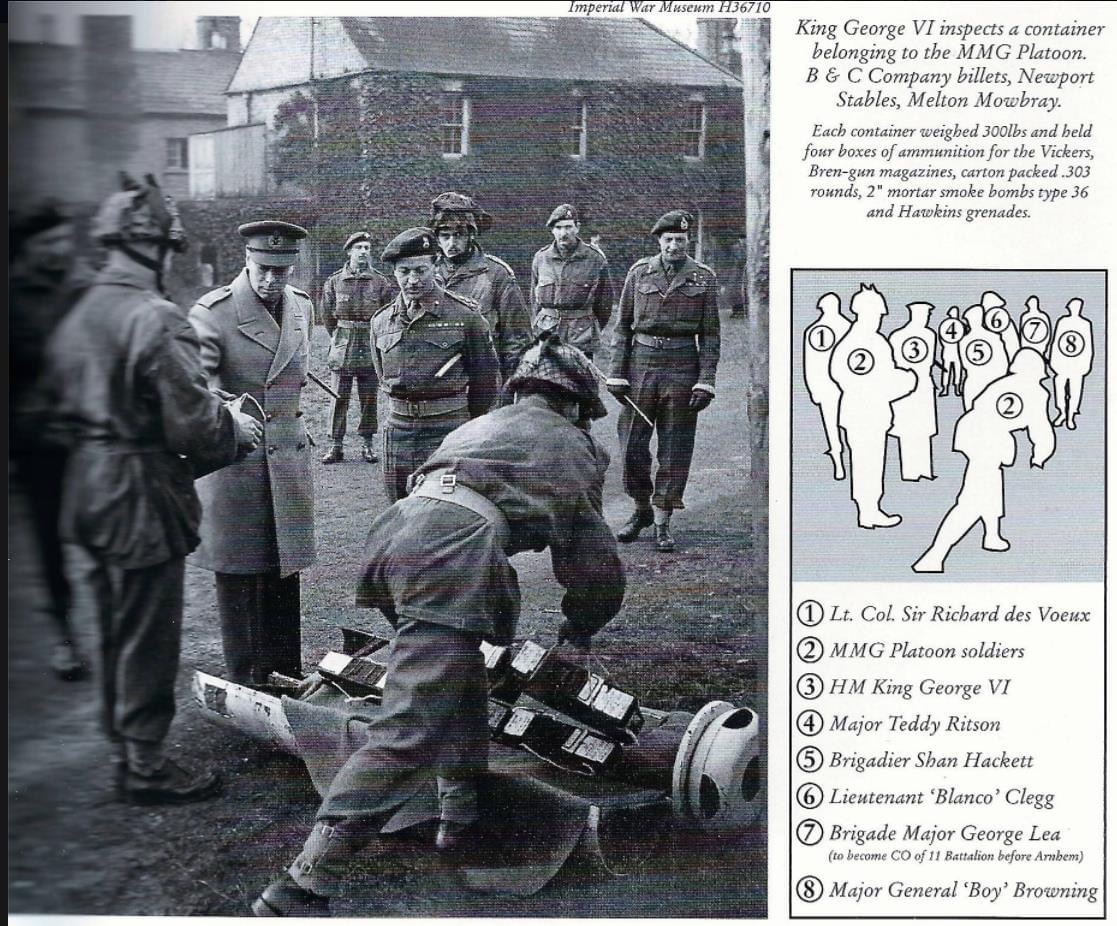

In India in 1941, Lea was among

the first to join airborne forces, becoming in 1943 brigade major of 4th

Parachute Brigade during operations with the 1st Airborne Division in

Italy. Within this organization was 11th Battalion of the Parachute Regiment.

The 11th Battalion had proved

to be something of a problem after a series of administrative mishaps,

and also the previous commanding officer was not a firm enough man to

whip the Battalion into shape. So in early 1944 he was relieved of his

post and replaced by George Lea, then Brigade Major, who was promoted

to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. In the coming months he made much progress

in bringing the 11th Battalion up to speed.

Lea and his men arrived in Arnhem on the second day of Operation Market

Garden. Upon landing, Lea was informed by Brigadier Hackett that the 11th

Battalion was detached from the Brigade and ordered to advance into Arnhem

to assist the 1st Parachute Brigade in their attempt to reach the Bridge.

However despite the need for urgency, the Battalion spent several hours

outside Divisional HQ until they received orders to move. When the order

came, they were skilfully led by some Dutch guides and with their help

they avoided a lot of German opposition and met with the 1st Parachute

Brigade during Monday night, having only suffered light casualties. Lea

arrived at the 1st Battalion HQ at about 02:30 on Tuesday 19th, and here

he conferred with Lt Col Dobie and Derek McCardie of the 2nd South Staffords.

It was decided their attack would commence at 04:00, with the 1st Battalion

and South Staffords leading the way, while Lea and his men followed on

behind in reserve.

The assault was viciously countered with heavy gun and mortar fire, and

continuous tank attacks. Both of the leading battalions were effectively

destroyed and George Lea was preparing to move his men in to assist, but

at 09:00 a vague order arrived on the radio from Major General Urquhart.

Having witnessed the fighting in the area, he decided that the 11th Battalion

should not move in to help as it would be an action that would only lead

to their unnecessary destruction. Lea ordered his men to hold and it was

a further two hours before fresh orders arrived for him. Urquhart now

charged the Battalion with the capture of some high ground in the area.

It was hoped that with this in their hands, the remainder of the 4th Parachute

Brigade would be able to make a successful attack in their direction.

Lt Col Lea gathered the remaining men of the South Staffords, now commanded

by Major Cain, and instructed them to capture some other high ground to

support their attack.

The 11th Battalion was engaged in heavy fighting by this time and it took

several hours for Lea to disengage his men from the battle, but they were

able to begin moving away by 14:30. Unfortunately the Germans realised

their intention and caught the whole battalion out in the open and cut

it apart with tanks and mortars. Only 150 men managed to get away from

the slaughter, however George Lea was not amongst them. He had been wounded

and was captured. He spent the rest of the war in a German prison camp.

After the war in 1946, Lieutenant Colonel Lea commanded the 15th (British)

Parachute Battalion until it was disbanded in December of that year.

In 1948 Lea married Pamela Elizabeth, daughter of Brigadier Guy Lovett-Tayleur.

His wife accompanied him wherever possible and contributed notably to

his accomplishments. They had a son and two daughters.

He continued his service with

airborne forces in India and at home, and in staff posts with the Royal

Marine commando brigade and NATO, as a lieutenant colonel, prior to taking

command of the Special Air Service regiment in 1955. Revived for the emergency

in Malaya, the unit lacked direction. Within ten days of his arrival,

a sergeant remarked: "the whole outfit came to life. He stretched

us-and himself-to the limit, but we could see it was leading to an operational

future."

On taking command, he immediately weeded out a number of unsuitable officers

and cast his eyes over the operational methods of 22 SAS. During the next

two years he developed the exacting standards and extraordinary skills

for which the Regiment became renowned and for which he was awarded the

Distinguished Service Order.

Fellow Lancashire Fusiliers who

served with 22 SAS, or its predecessor the Malayan Scouts, included Major

John Harrington, Captain Ian Cartright, Captain Billy Crawshaw, Captain

Ray England, Captain Rodney Carey, Staff Sergeant "Rocky" Mountain,

Sergeant 'Chopper' Essex, Corporal Geoff Brighouse, Corporal Geordie Plant

and Corporal Harry Goodman. A young Lieutenant Peter de la Cour de la

Billiere of the Durham Light Infantry, who was later to command, also

joined the Regiment during his tenure.

In the summer of 1955, a squadron

of SAS was raised in New Zealand and after rigorous selection and basic

training arrived in Malaya towards the end of the year, where they carried

out their parachute course. The total strength of the squadron was 140,

a third of whom were Maoris who found it easy to work with the aborigine

tribesmen. After a brief shakedown period they went on to make a valuable

contribution to the strength. Another squadron was added at the end of

1955, formed from volunteers from the Parachute Regiment where it was

known as the Parachute Regiment Squadron and commanded by Major Dudley

Coventry. These additions brought the strength of 22 SAS to 560 all ranks,

divided into five squadrons each with four troops of sixteen men, plus

headquarters personnel and attached specialists.

A normal pattern for a squadron was two months in the jungle, two wild

weeks of leave, two weeks retraining and then back to the jungle. There

were courses to be taken, new skills to be learned and training was continuous.

Lieutenant Colonel Lea instituted additional training for warfare worldwide

to secure the SAS a life after the emergency in Malaya ended.

By the end of 1955 the back of the Malayan terrorist campaign had been

broken and murder of civilians was down to five or six a month. The leadership

had fled to Thailand and the policy of rewarding defections had paid off.

Low flying aircraft equipped with loudspeakers made tempting offers of

money and food. During 1955, the Parachute Regiment Squadron operated

in the Ipoh area, hitting the headlines when they killed a woman terrorist,

'capturing' her six-month old baby, which they discovered afterwards and

then took care of the infant. 1956 and 1957 saw the SAS campaign wound

down. The Regiment had played a major role, and at the end of 1956 its

official score was 89 terrorists killed and nine captured. The momentum

was maintained with patrols that served to maintain the pressure on the

remaining terrorists.

In April 1957, the Parachute Regiment Squadron returned to England and

the New Zealanders also left, having accounted for fifteen terrorists

in their two-year tour. By then, 22 SAS was a highly trained regiment,

experienced and equipped with new weapons, skills and tactics and an adaptability

that would be proved time and time again in the future. For this, great

credit must go to the leadership and vision of George Lea.

Major Maurice Taylor, another Lancashire Fusilier then flying as an army

pilot recounts, "a nicer man you would never wish to meet and obviously

a great soldier. Great was the operative word too when you picked him

up in an Auster; about 250 lbs of him with a 60 lb Bergen usually with

another small giant with an even bigger Bergen and their weapons......talk

about scraping off the improvised airstrips we flew from back in those

days!"

As a consequence of his success

with 22 SAS, Lea was promoted directly to a brigade command in England

in 1957. He was then competing with peers in the more favoured armoured

warfare environment in Germany.

Appointment to command the 42nd

Lancashire Territorial Division and North-West District in Preston, Lancashire,

in 1962 appeared to limit his further employment. But he was selected

in 1963 to the politically sensitive command of the armed forces of Northern

Rhodesia and Nyasaland, colonies moving imminently to self-government.

His political tact and decisive containment of dissident groups were judged

exemplary. As this task concluded, he was chosen to succeed General Walter

Walker as Director of Borneo Operations early in 1965. His successive

aides-de-camp during these three command appointments were Captains John

Steeds, Lawrence Stacey and Christopher Berry of XX The Lancashire Fusiliers.

Responsibility for the civil

government of the former British Borneo territories had passed to Malaysia,

whose authority was disputed by neighbouring Indonesia and Chinese communists

in Sarawak. Lea was required to secure a mountainous border 1000 miles

in length amid dense jungle, and to pacify the communist faction. He served

three authorities: the British commander-in-chief in Singapore, the Malaysian

government in Kuala Lumpur, and, to an extent, the Sultan of Brunei.

Lea possessed only a proportion

of the powers necessary to ensure the co-operation of civil government,

the Malaysian police and armed services, and the Australian and New Zealand

sea, land, and air elements which reinforced his British forces from time

to time. The rest depended upon goodwill, which he won by his open manner,

humour, and modesty. Nothing ruffled him. Even when his wooden house caught

fire and he lost in minutes the greater part of his personal possessions,

he continued as if it were a matter of the least importance.

Making adroit use of air and

sea resources, Lea developed the policy of pre-emptive cross-border strikes

by his troops, while containing the Chinese communists with police backed

by military units. The success of these methods contributed to the change

of political leadership in Jakarta and the emergence of an accord between

Indonesia and Malaysia in 1966.

Promoted to lieutenant general,

he was posted in 1967 to Washington, DC, as head of the British Services

Joint Mission, the link between the British and American Joint Chiefs

of Staff. Maintaining the close alliance in a period of British economic

difficulty and defence retrenchment was not easy. But the Americans opened

their offices and confidences to him more fully than protocol demanded,

because they liked and respected him, as the chairman of the American

Joint Chiefs observed on his retirement in 1970. He had evoked similar

responses throughout the greater part of his professional life

Colonel of XX The Lancashire

Fusiliers from 1965 to 1968, George Lea was deputy colonel and then colonel

(1974-7) of the Royal Regiment of Fusiliers. He was appointed MBE (1950),

CB (1964), KCB (1967), and to the DSO (1957). For his services in Borneo,

he was made Dato Seri Setia, Order of Paduka Stia Negara, Brunei (1965).

He retired to live in Jersey and died at home in St Brelade, Jersey, on

27 December 1990.

Gen Darling and Gen Lea

sent in by

Mike Murray

|