|

Lutyens’

Memorial, |

Lutyens Memorial Now

Outside the Museum in Gallipoli Garden Silver St Bury VJ 75 2020 |

Lutyens’

Memorial, |

|

The

1881 Census for Wellington Barracks and the the Militia Barracks Click here to see some more photos of Bury and Wellington Barracks |

|

Bury Wellington

Barracks |

|

|

We think 1955 to 1957

We think the Sgt is Greenwood 2nd in in front rank Alan Bimpsom 1st guy front rank is one of the Tooth Family

half face 2nd in one of the Pollitts

|

|

National Service, 1959.

By Tony Bowles I was home from work as usual about 6pm, but

there was a strange atmosphere. 'there's a letter from 'On Her Majesty's

Service' My call up papers had arrived at long last. We met in Bolton for a last pint as civilians at a pub just twenty yards from the 23 bus service to Bury. Looking at two years then it seemed a lifetime, looking back now at fifty years ago this year I wonder how it went so fast. We arrived at Wellington Barracks somewhere

around mid day and were ushered to the canteen for a taste of army food

and our first taste of army life. It was also my first taste of meatballs

and string beans. I was gobsmacked to be served by a cousin of mine

serving with the Catering Corp. Among our training groups were a few young

lads who were in between the two intakes, regulars who had signed on

then mixed in with us. They were quite valuable in that they had already

picked up a few 'wrinkles', bulling the pimples from our new boots,

how to blanco, polish brasses, square our beds, press BD's, in fact

all the basics, the best sergeants, the worst NCO's, we had apparently

the best sergeant, sergeant Bill Pritchard, under him we would have

the best platoon award. The three platoons would bring about a highly

competitive edge to our training, ideal for honing teamwork to a high

standard. Sergeant Pritchard was a confident man, although it maybe

inspiring to his wards he predicted we would be 'best platoon' and not

only that, we would also furnish the 'best recruit'. He was right on

both counts. As a footnote I might add that the summer of 1959 was one of the hottest and longest, for a period, water was only turned on for a few minutes in the morning and the same again in the evening, you had to be quick so as not to be on a charge for parading unshaven. Water carts were sent out to outlying districts, it was a very serious situation. Eventually those living within travelling distance were allowed home for the weekend to have a decent bath. Tony Bowles, signals platoon 59/61. |

Click on the link below to see the history of the Bury Drill Hall

http://www.mbbcanal.demon.co.uk/trail/bury/castle/castle.html

|

|

|

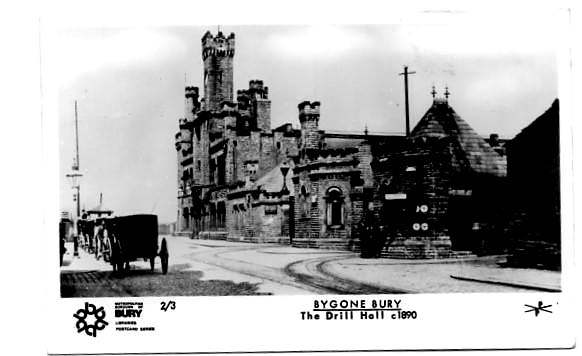

HISTORY OF CASTLE ARMOURY

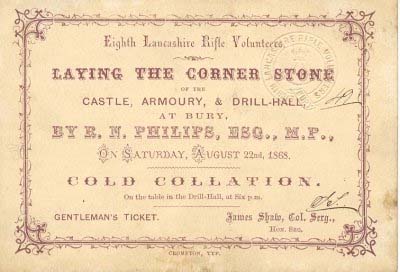

In 1859, the 8th Lancashire (Bury) Rifle Volunteer Corps was formed, raising the problem of providing shelter and drilling facilities for the new unit. A new Drill Hall was proposed, funded for by public subscription and a former Bury Member of Parliament, Mr R N Philips, laid the foundation stone of the Drill Hall on a typically wet Bury day in August 1868.

The Drill Hall was built on the historical site of Bury Castle, a 13th century Keep owned by the powerful Pilkington family, Lords’ of the Manor of Bury. It incorporated some original castle material into its structure and a section of the original moat is preserved in front of the present building. In keeping with the 13th century architecture of the castle, the new Drill Hall was built in a fortified style. Castlellations, gargoyles, turrets, towers, arrow slits and other Norman architectural features contributed to the ancient-looking façade. In the 1880s with the advent of steam engines, a tram depot was built next to the Drill Hall using the same architectural features. This building, however, made way for a new Drill Hall extension in 1907.

The opening of the Drill Hall extension also marked one of Bury’s royal visits. HRH The Duke of Connaught, brother of King Edward VII officially opened the building on 23rd November 1907. A year earlier Colonel George Edward Wike, the Commanding Officer of the Bury Volunteer Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers (1900-1907), personally raised £7,500 for the new building extension and was given the privilege of laying the foundation stone on a bitterly cold autumn morning in October 1906. Subsequently Colonel Wike was made a Freeman of the Borough in 1911. The Drill Hall extension kept to the same style as the original building. A new main gate was built into the extension, consisting of a large semi-circular arch, decorative columns and timber portcullis, flanked by the building dates 1868 and 1907. Above the gate a large Coat of Arms is present, incorporating the Lancashire Fusiliers badge and motto “Omnia Audax”, translating to “Dare Anything”.

The Lancashire Fusiliers date from the landings of Prince William of Orange (later King William III) at Torbay in 1688, when he was met by a number of noblemen who were then commissioned to raise Regiments for his service against the deposed James II. Colonel Sir Robert Peyton, one of these, had served under the Prince in Holland and raised a Regiment of Foot containing six independent companies in the Exeter area. In 1782 the title was changed to the XX or East Devon Regiment of Foot and from the 1st July 1881 as XX The Lancashire Fusiliers. The historical link between Bury and the Fusiliers started during the latter part of the 18th and early part of the 19th century. The XX had been very successful in recruiting from the Lancashire area and a Regimental Depot was established at Wellington Barracks, Bury in 1881, following the renaming of the regiment. Wellington Barracks became XX The Lancashire Fusiliers Regimental Headquarters in 1961.

A Reserve Forces Corps of Lancashire Volunteers had already been firmly established at Castle Armoury since 1868, later becoming The Lancashire Fusiliers 5th Battalion (Volunteers). In 1968 The Lancashire Fusiliers became part of the newly formed Royal Regiment of Fusiliers.

January 1943 was a terrible year in Castle Armoury’s long history. A member of the National Fire Service, Fireman Walter Sunderland (39) died tackling a ferocious fire at the site. An explosion rocked the building and threw Fireman Sunderland and several colleagues through the windows. He died of his injuries, while others were taken to the infirmary. Almost the entire building was destroyed, with hundreds of shop windows blown out along The Rock. The nearby church took full force of the blast with £1,000 of damage to its stained glass windows. While many other cities and towns had their centres destroyed by Nazi bombing raids, Bury’s was destroyed from within. It was not believed that arson was to blame for the tragic events, however evidence later suggested the fire originated in or near to the heating apparatus. The fire was discovered at approximately 6 am, the alarm being raised by a local railway worker. Firemen from Bury and the surrounding districts were rushed to the scene. They at once concentrated their efforts on preventing the fire spreading and tackled the flames from inside the building. The fatal explosion occurred at 7.30 am. An inquest was opened on Fireman Sunderland’s death at the Coroner’s office, Colonel R.M. Barlow adjudicating. A verdict of accidental death was recorded. It is often said that the spirit of Fireman Sunderland haunts the Officers’ Mess, where the accident happened.

A severe labour shortage in 1951 caused serious delays to the Drill Hall extension and restoration after the fire. Work completion was expected for the end of 1951, but took a further six months to complete.

Three plaques adorn the East wall of the Drill Hall commemorating those who fell in two World Wars and the Boer War. The Lancashire Fusiliers has a proud history, winning many Victoria Crosses for its soldiers’ heroism, notably the ‘six VC’s before breakfast’ won at Gallipoli in 1915. 129 officers and men fell before successfully capturing the beachhead.

After the Labour Government’s

Strategic Defence Review in 1998, the Fusiliers at Bury were merged

into the Lancastrian and Cumbrian Volunteers. For historical reasons

their name was preserved in the new title deeds, so a platoon of Fusiliers

still resides at Castle Armoury, proudly displaying a hackle with their

cap badge. Castle Armoury is also home to the Head quarters East Lancashire

Wing of the Air Training Corps and the Bury Detachment of the Manchester

Army Cadet Force. In addition G Squadron of 207 (Manchester) Field Hospital

(Volunteers), arrived as the lead unit in the summer of 1999. It is

envisaged that Castle Armoury will continue to provide suitable training

and social amenities for members of the Territorial Army and the cadet

organisations for many years to come. |

|

A

|

B

|

C

|

D

|

|

|

1.

|

||||

| 2. | ||||

|

3.

|

||||

|

4

|

||||

|

5

|

||||

|

6

|

||||

|

7

|

||||

|

8

|

||||

|

9

|

||||

|

10

|

||||

|

11

|

||||

|

12

|

||||

|

13

|

||||

|

14

|

||||

|

15

|

sent

in by Dave Rowland

Harry Rowland is 5th from the right front row he is davids dad |

|

|

|

|

This photo was found by Steven

Fitt

Comments from Maurice Taylor Nice one of Minnie and Fusilier Albert Dwyer The officer turning round is Lt Col Bowen, CO of 1LF. You might know there were twin Bowen brothers Charles and Hugh both in the Regiment pre war. I think eventually one commanded 1LF and the other 2LF but don't quote me on that it needs to be confirmed. I know they were both good sprinters and they ran for England in the 1936 Olympics in front of Hitler. Sadly in 1961 Hugh Bowen (Junior) joined me as a 2/Lt in Osnabruck fresh from Ampleforth and Sandhurst. The Catholic padre was going on a retreat to Lourdes and I asked Hugh would he like to go. En route to France with the Padre driving they had an accident and Hugh was killed outright, the Padre was knocked about, broke hips etc so a promising young officer had his life taken away....I think he was only 21 and had been with us for just a couple of months...I went to his funeral somewhere near Southampton with David Lloyd Jones. His mother was heart-broken. The officer behind the CO is then Captain Jimmy Grover who was sometime Adjutant and later became our CO in Osnabruck. Jimmy Grover did not last long he died of a heart attack shortly after he handed over he must have been in his early forties I think Jim Wilson followed him? We were all hoping for a Lancastrian at the time, Jim Martlew, but the powers that be imported an outsider...shame. The Pioneer Sgts I cannot place? |

|

"1959 Visit to MINDEN

Bicentenery and Nijmegen march."

|